By Joy Macready

The struggle for women’s rights exploded towards the end of the 19th Century, as hundreds of thousands of women in the industrialised countries were drawn into mass production. Pulled out of the private sphere of the home, they were thrust into the public workplace, where they shared a common experience with other working-class women and men.

However, despite working alongside men in factories, women’s pay was significantly lower; they weren’t allowed to be members of trade unions and were barred from voting as well as from joining political parties. Additionally, they were second-class citizens in a legal sense: divorce was restricted and men owned women’s property.

Women also faced a double burden of work in the factory and housework at home. They often faced domestic violence in the family.

Clara Zetkin, a key figure in the world’s first mass socialist party, the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), led the battle for women’s rights and fought to lay the basis for a socialist-led, working class-based, women’s organisation.

In 1891, she was instrumental in launching Die Gleichheit (Equality), subtitled “for the interests of working women”. Its express purpose was to provide women comrades in struggle with a clear Marxist understanding of women’s oppression, to enable them to place themselves on the secure base of Marxist politics.

The network created by Die Gleicheit helped to dramatically increase women’s membership of the SPD from 4,000 to 82,642 between 1905 and 1910.

Challenging sexism within the movement

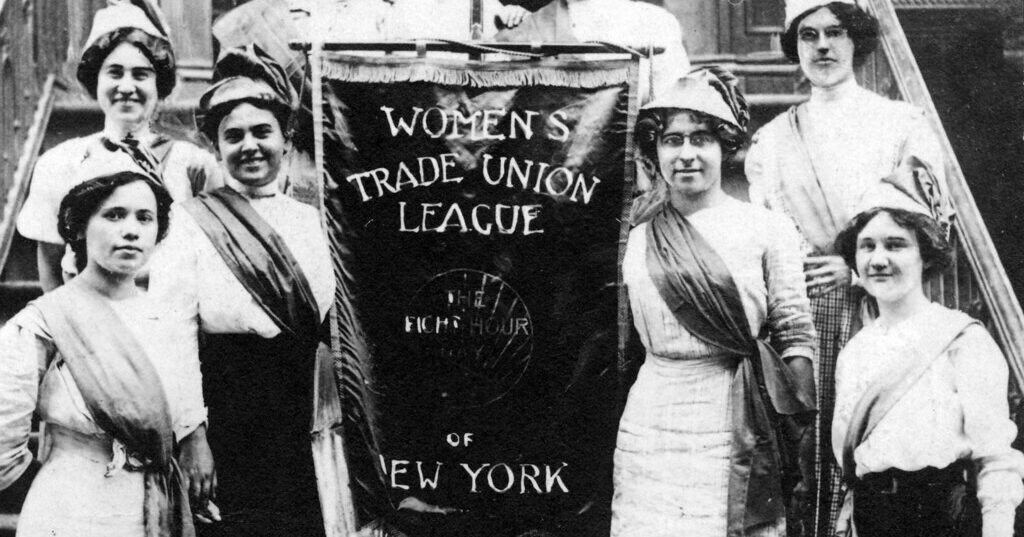

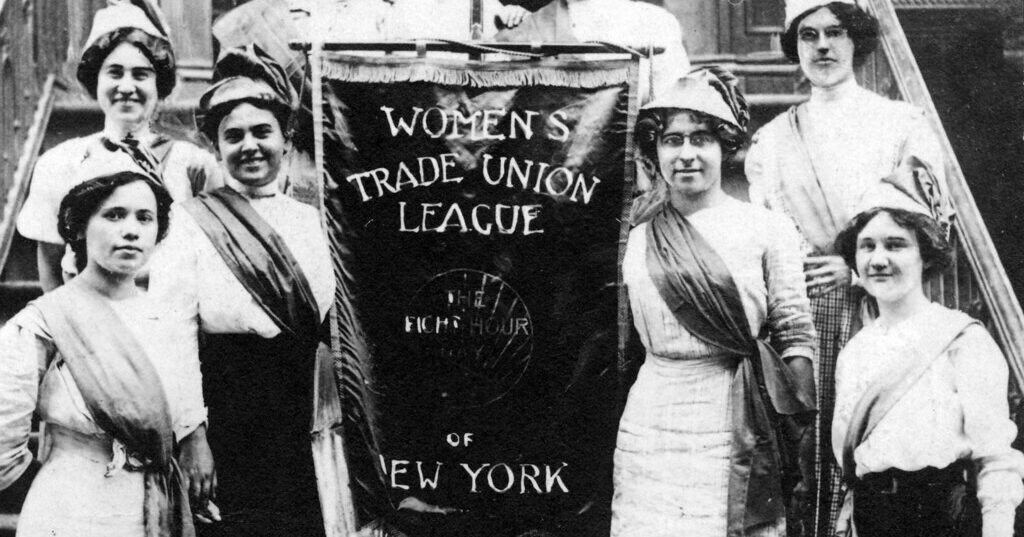

First, however, Zetkin and her co-thinkers had to overcome hostility to the involvement and demands of militant women within the party itself. In addition, trade unionists in the wider labour movement were fearful that women workers would threaten their jobs and bargaining position.

Speaking at the Party Congress in 1896, Zetkin argued for the inclusion of women in the political struggle of the working class. Following Fredrick Engels, she said that the root of women’s oppression lies within the family, that there is an inseparable connection between the social position of women and private property in the means of production. Without a socialist revolution, women’s liberation could not be achieved and, without involving women in the class struggle, the socialist revolution itself would be impossible.

She countered the men’s fear that working women would undermine their position by arguing: “The more women’s work exercises its detrimental influence upon the standard of living of men, the more urgent becomes the necessity to include them in the economic battle.”

Internationalism

Zetkin made the struggle for women’s rights international. In 1907, she organised the first International Conference of Socialist Women, attended by delegates from 15 countries, to coordinate the struggle for the vote and build mass socialist women’s organisations worldwide.

In 1908, on 8 March, 15,000 garment workers marched through New York’s Lower East Side to demand an end to the dangerous conditions at work sweatshops, violence against women at work, child labour and the right to vote. What they were fighting against was brutally demonstrated two years later in New York’s garment district with the horrific Triangle Shirtwaist fire in which 146 workers perished.

In 1910 the American workers’ struggle went global. At The second International Socialist Women’s Conference in Copenhagen, Zetkin proposed adopting March 8 as a day of celebration and struggle for working class women.

At the second conference, in 1910, she argued for an International Women’s Day. On March 19, the following year, rallies in Austria, Denmark, Germany and Sweden were attended by over a million workers, under the slogan: “The vote for women will unite our strength in the struggle for socialism.”

This all took place as part of a worldwide socialist movement, united in a single organisation: the Second International. But tragically the Second International broke apart with the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, when the leaders of the SPD and its other national parties supported their “own” capitalist governments in war.

Zetkin stood up against chauvinist hatred, together with revolutionaries like Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. Their tiny grouping bravely opposed the war, and denounced the SPD leaders for betraying the international working class by supporting the slaughter.

Zetkin, as the secretary of the International Bureau of Socialist Women, called a conference in Bern at the end of March, 1915. Women from Poland, Britain, Germany, France, Italy, Switzerland and Russia attended. This conference was the first to re-raise the banner of internationalism and struggle against the war. It issued a call that concluded:

“The working people of all countries are brothers. Only the united determination of the people can stop the slaughter. Socialism alone is the future peace of humanity. Down with capitalism, down with the war, onward to socialism.”

She remains an inspiration to socialists today. Zetkin showed how socialists need to fight for the rights of women even within their parties and unions, how the unity of the women and men of the working class has to be fought for every day, and how millions of working class women can be rallied to take their place alongside men in the fight for socialism.