By Robert Teller

The fact that ‘Two States’ in Palestine – one for Israeli Jews, another for Palestinian Arabs – will never become a reality does not mean that the idea cannot serve a purpose of its own.

While Israel’s carpet bombing of Gaza lays waste to neighbourhoods, bakeries, hospitals and government buildings – and in doing so, pulverises any path to Palestinian statehood – the ‘two-state solution’ is once again haunting the minds of those among Israel’s friends who consider it morally imperative to also think about a ‘time after the war’.

UN Partition Plan and Nakba

The origin of the ‘two-state solution’ is the UN partition plan of 1947, drawn up because of Britain’s desire to withdraw from Palestine. Although the creation of a single federal and democratic state in all of Palestine was discussed, the UN finally decided on a partition that envisaged most of the country as a ‘Jewish’ state, while Jerusalem was to be placed under UN administration and an ‘Arab’ state created on the remaining land. Both states would be politically sovereign, but connected in a common economic zone.

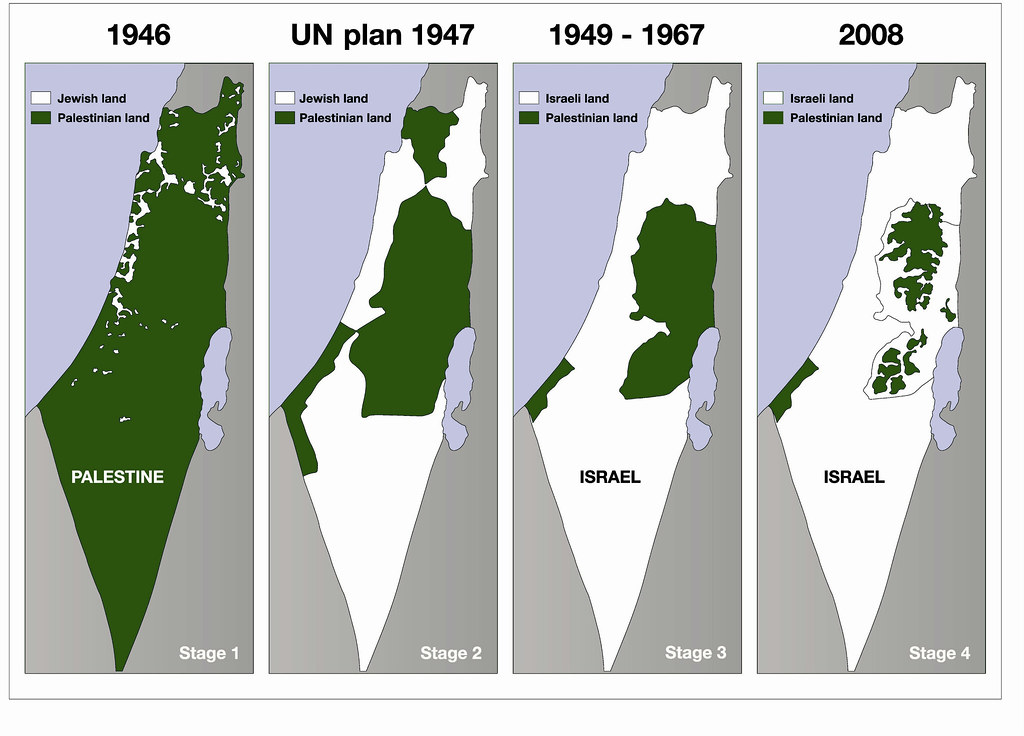

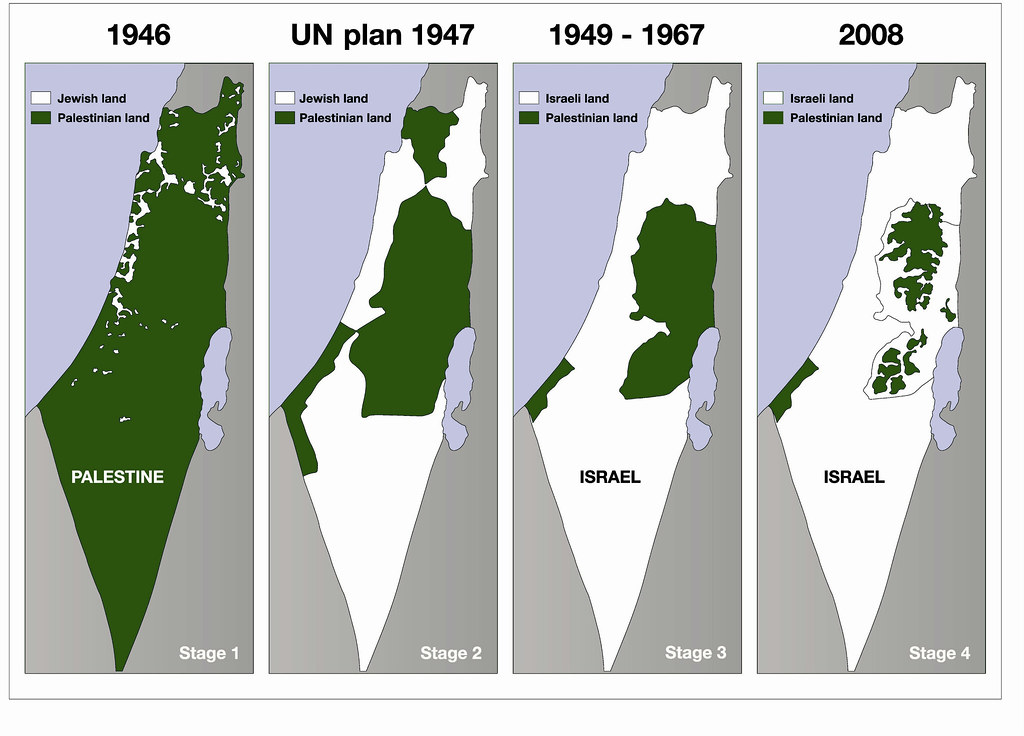

Even then, this division was disproportionate, with 56% of the country given to Jewish immigrants who constituted only 32% of the population and owned just 7% of the land. Some 400 Palestinian villages fell within the proposed boundaries of a ‘Jewish’ state. Unsurprisingly the Palestinians rejected the cession of territories to the colonial settler movement. From the outset, the plan violated the idea of sovereignty, a principle on which the UN was founded.

The partition plan, which had no democratic legitimacy, did nothing to defuse the tensions between the Zionists and the indigenous population. Instead, it gave political and moral backing to the forcible expulsion of 700,000 Palestinians and the murder of thousands more in 1948. The Nakba ended in the military conquest of a territory that went well beyond the plan, with 78% of the land ending up in Israel’s hands. These forcibly created borders were internationally recognised in 1949 by armistice agreements, which left Egypt in control of Gaza, and Jordan in control of the West Bank.

Israel has never fulfilled the obligation imposed in UN Resolution 194 to allow all Palestinian refugees to return – and this was never seriously discussed in the ‘peace process’ that should have led to a two-state solution. On the contrary Israel’s prerequisite for ‘peace’ was unconditional recognition of the conditions created in 1948, which have since turned generations of Palestinians into refugees in their own country or in neighbouring states.

The ‘two-state solution’ did not resurface until 1967, when Israel was confronted with the ‘problem’ of what to do with the West Bank and Gaza, which it had conquered during the Six-Day War. The ‘solution’ of permanent military occupation and settlement without annexation (which would have posed the problem of granting democratic rights to the Palestinian population), started to fall apart by the mid-1980s.

Collective forms of struggle by the Palestinians, such as strikes and boycotts, culminating in the First Intifada between 1987 and 1993 dealt severe blows to the Israeli economy. The post-1967 strategy of economic integration and development of the occupied territories – while denying all democratic rights to the Palestinians – threatened to undermine the Zionist project as a whole.

Oslo

The central promise of the Oslo Accords in 1993 was Israel’s withdrawal from the West Bank and Gaza Strip. However, this was only to be done at the conclusion of a five-year process that would shift responsibility in small steps towards the newly created Palestinian Authority. Until then, the Palestinians were to be on probation and demonstrate that they were ‘ready for peace’. On the Israeli side, an important aspect was to relieve the army of policing responsibilities for the occupied territories – in order to expand its military capabilities.

The question of economic integration, however, was controversial in the Zionist camp. Israel’s sole control of borders and foreign trade since 1967 had allowed the Israeli economy to reap extra profits through the super-exploitation of the Palestinian working class. Although the economic union and freedom of movement for Palestinians were contractually agreed in the Oslo Accords, the wing of the Israeli security apparatus that saw a common Jewish-Palestinian economic space as an unacceptable ‘security threat’ ultimately prevailed.

The increasing blockade of the West Bank and Gaza Strip was a clear violation of Oslo, but Israel pursued it to minimise the ‘danger’ that comes with responsibility for the occupied people. Although freedom of movement post-1967 had been subject to Israeli military control, it was not until the mid-1990s that the closure of villages, towns or the entire West Bank, or the imposition of curfews became everyday normality.

Another important consequence of the Accords was the fragmentation of the West Bank into a patchwork quilt with a graduated division of tasks between the Israeli military and the Palestinian Authority (PA). According to the initial plan, Israeli withdrawal from Area A and Area B was to be the first step towards Palestinian self-determination; by the end of 1999 the entire West Bank was to be handed over to the PA.

In the end, only the withdrawal from Areas A and B was implemented, which since then have largely been enclaves under the control of the PA’s police, loyal to Israel. Even here Israel reserves the right to intervene militarily.

In reality Israel enforced conditions in each partial withdrawal that took into account its long-term goal of colonising the West Bank. For example, when Israel withdrew from Hebron in 1997, a permanent military presence was agreed to ‘protect’ the then 400 Israeli settlers. One consequence of this agreement is that 20,000 Palestinians in the Israeli-occupied H2 zone of this city had to subordinate their lives to the military needs of the inner-city settler colony. Curfews, ‘sterilised’ (i.e., ethnically cleansed) streets, checkpoints and electronic surveillance established an apartheid system.

The ‘two-state solution’ of the 1990s presupposes two conditions on the part of the PA: on the one hand, the recognition of all injustices committed before 1967 as an immovable fact; and the demobilisation of the intifada and disarmament of the PLO. Thus facts were created in favour of Israel. The crucial issues were tellingly postponed to the indefinite future: the right of return, Israeli settlements, foreign relations of the Palestinian state and the future status of Jerusalem (which had been annexed by Israel in 1980 in violation of international law).

As vague as the agreement was on all essential points, not only did it demand tangible concessions from the Palestinians, it was also intended to delegitimise the expression of every conceivable Palestinian demand as ‘sabotage of the peace process’. The Palestinian side had a duty to prove itself a ‘partner’ of Israel before it was worthy of a ‘real’ agreement.

The Israeli side, on the other hand, interpreted the agreements reached, as being able to block any small step towards Palestinian independence, citing ‘security concerns’, while the Palestinian concessions – especially the territorial division of the West Bank – remained final. Since then, the only thing that has been considered worthy of discussion is the restitution of individual scraps of land in the West Bank – to which Israel has no territorial claim. Sovereignty over borders, airspace and coastal waters, even the right of Palestinian refugees from neighbouring countries to return to these Palestinian Bantustans – all supposedly violated Israeli security.

By the time the second Intifada began in 2000, it was clear that a final agreement on Israel’s withdrawal from the West Bank was out of reach. Since then agreements signed by a politically broken PLO under Yasser Arafat have served as political legitimacy for the indefinite occupation of Area C and the massive transfer of settlers there as human shields for the occupation.

Instead of achieving limited Palestinian self-determination, Oslo has made Palestinians strangers in an area that differs from Israel’s heartland only in the sweeping privileges with which the Israeli state rewards settlers for their function as civilian occupiers. This de facto annexation of Area C avoids increasing Israel’s responsibility for the Palestinians (racially referred to as a ‘demographic threat’).

For supporters of Israel, an alleged threat to settlers legitimises any conceivable harassment of Palestinians. Notwithstanding the hypocritical hope, especially in the West, that after Oslo it would somehow be possible to conclude with Palestinian demands, the real consequence of the agreements was their systematic fencing with a now deadly barrier around Gaza and a system of walls, checkpoints and apartheid roads that run through and delimit the West Bank. The only Palestinian airport, supposedly a symbol of newfound Palestinian freedoms, was destroyed by the Israeli Air Force just three years after it opened.

The Palestinian Authority was to become the local administrator of the status quo of the occupation after Israel cut its cord. In addition, the apparatus, which depends on foreign ‘aid money’, offers all sorts of ‘friends of the Palestinians’ the opportunity to financially compensate for their complicity with Israel.

Although the shift to the right in Israel after Oslo dispelled any illusion in a peaceful solution, the disastrous consequences of the ‘peace process’ for the Palestinians were not due to its failure, but inherent in it from the beginning. Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, who was glorified as a peacemaker after his assassination in 1995, left no doubt that the agreements he had drawn up were not intended to result in Palestinian sovereignty and that Israel’s ‘security border’ would always lie along the Jordan River.

Another important takeaway from Oslo, however, is that even the complete political capitulation of the once-self-confident PLO was not enough to put the Palestinian issue to rest. The second Intifada proved once again that Palestinians were still capable of mass resistance.

Israel’s response – the renewed military advance into Areas A and B, the siege of Yasser Arafat’s headquarters in Ramallah, the destruction of the civilian Palestinian administration in the West Bank and the routine imposition of collective punishments, such as curfews, lockdowns or house demolitions – also made it clear that the core of the conflict is not Palestinian unwillingness to find a peaceful settlement, but Israel’s ability and will to enforce the status of Palestinians as displaced and disenfranchised.

The intentions of the Israeli government were very clearly formulated before the Israeli withdrawal from Gaza in 2005 by Dov Weissglass, then an adviser to Prime Minister Ariel Sharon:

‘The importance of the disengagement plan is that we freeze the peace process. And if you freeze this process, you prevent the establishment of a Palestinian state and prevent a discussion about the refugees, the borders and Jerusalem. The whole package called the Palestinian state, with all that it entails, has been removed from our agenda indefinitely.’

As with any use of military means, the actual prevailing relationship of force is the yardstick for any ‘peace plan’. The ‘Roadmap for Peace’, relaunched by the United States in 2002, made significant concessions to the Israeli side. Israel interpreted the Roadmap as making the end to the Intifada, the disarmament of the Palestinian security apparatus and the removal of Yasser Arafat from power all preconditions for further progress. For Israel, therefore, the Roadmap had the function of providing political legitimacy for the suppression of the Intifada.

Role of Gaza

Another important aspect of Israel’s policy post-Oslo was to fragment the Palestinians, both geographically and by presenting to them different experiences of the occupation. As we have seen, the experience of Palestinians in the West Bank, according to whether they lived in Area C or Areas A and B, began to diverge. In addition of course the 1.6 million Palestinians living inside Israel suffer under a different form again of the Israeli apartheid system. But it is Israel’s treatment of Gaza that underpins this system of graduated humiliation and degradation.

As the Weissglass quote above shows, Israel’s withdrawal of troops and settlers from Gaza in 2005 was designed to remove the possibility of a Palestinian state ‘from [Israel’s] agenda indefinitely’. The inevitable election of Hamas in Gaza in January 2006 was the first step towards this, dividing the Palestinian leadership and, through pressure on Fatah, turning them against each other, culminating in the so-called Brothers’ War of June 2007, which resulted in the expulsion of PA forces from the Strip.

Israel and its Western allies immediately turned the screw on the Gazans, controlling the borders so tightly that aid and trade, by air, sea or land, could be monitored, controlled and turned off at will. The US, EU and UK also switched off all aid from Hamas and Gaza, channelling any support through the Fatah-controlled PA. They then designated Hamas as a terrorist organisation to further isolate Gaza and its elected leadership.

Collective punishment in Gaza took on a far more deadly and terrifying form with assassinations of Hamas leaders, their families and neighbours, and periodic invasions of the territory, with Operation Cast Lead (2008-09), Operation Pillars of Defence (2012) and Operation Protective Edge (2014) being the most prominent examples before the current war.

Whenever Hamas appeared to be gaining support in the West Bank or steps were taken to form a united front with Fatah, Israel responded by sending fighter jets, tanks and troops against the defenceless civilian population. Their message was clear: get too close to Hamas and armed resistance, and this is what could happen to you.

Deal of the Century

For almost all observers the Trump plan of 2019 (‘Deal of the Century’) was ultimately just an attempt to legitimise reality by casting it into a permanent legal form. Part of the plan was the unilateral annexation of all settlements in the West Bank and Jordan Valley, which would only have to be ‘approved’ by the United States.

The Palestinian ‘state’ would not be allowed to maintain any armed organs, would have to refrain from any legal action against Israel in international tribunals and would not be allowed to join international institutions on its own behalf. Violation of any agreements would automatically give Israel the right to intervene militarily, subject again only to the approval of the US.

The plan includes Israel’s right to expatriate Palestinians with Israeli passports and further annex areas of the West Bank in ‘exchange’ for territories in the Negev desert. The annexation of Jerusalem would be recognised, all borders would be controlled exclusively by Israel and the return of Palestinian refugees even to this ‘state’ of Palestine would be subject to Israeli approval.

With the ‘help’ of investors from the Gulf states, the Palestinian cantons were to be developed into a thriving special economic zone. In this way, the rest of the world was to be relieved of the financial burden of providing a large part of the Palestinian population with basic necessities through UNRWA, which has been a central prerequisite for the permanent ghettoisation of Palestinian refugees and thus Israeli ‘security interests’ since 1948.

For Israel, the ‘two-state solution’ has served its purpose – the political subjugation of the PLO and the elimination of any alternative resistance movement, e.g. Hamas. At the same time, it has served as a fig leaf for the EU, US and UK governments for three decades to cover their continued support for the colonial state of Israel. This also explains why it may not disappear from people’s minds as easily as the Zionist right in Israel would like.

Another result of the Oslo Accords is the apparatus of the Palestinian Authority, which has become indispensable for Israel as a sub-contractor for the occupation regime. This explains the readiness demonstrated by President Mahmoud Abbas and Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh to step in as governors over the rubble after the end of Israel’s war in Gaza. The fact that the Israelis have so far ruled this out underscores the reality that only Israel has any real authority between the River and the Sea.

It is not only questionable where the Palestinian Authority is supposed to get the necessary authority for the reorganisation of Gaza. The political unification of Gaza with the West Bank would also present the long-discredited PA as a common enemy to all the Palestinian masses and raise opposition to its rule as an all-Palestinian issue, as a central aspect of the struggle against occupation and oppression in general.

Bi-national socialist state

The impasse in the discussions over the two-state solution simply shows that the solution of the Palestinian question is at odds with the continued existence of a colonial, ethnically cleansed state of Israel – within whatever borders. Its revolutionary overthrow is the prerequisite for the realisation of the right to self-determination of both nations, the Palestinian and the Jewish-Israeli.

In addition to the complete legal equality of both nationalities, the recognition of all spoken languages as equal, the recognition of the right of return for all Palestinian refugees worldwide and their right to compensation, this also requires breaking the ideological attachment of the Israeli masses to the Zionist project. As long as Jewish-Israeli self-determination is falsely equated with the maintenance of militarily secured, imperialist sponsored and apartheid racist state, a just solution remains an impossibility.

However, this breakaway of the Israeli masses from Zionism cannot be a precondition for the Palestinian liberation struggle. Rather, any blow that the Palestinians and the international solidarity movement inflict on the state of Israel will also weaken the foundation of this ideological bond, which is based on the chauvinist belief in Israel’s invincibility.

Even if the struggle against settlement construction and the daily attempt to expel Palestinians from the West Bank is the task of the day, the resistance must aim at the recognition of the rights of the Jewish-Israeli nation, albeit with the complete abolition of all privileges. This objective, however, is also incompatible with the existence of two states.

The two-state solution would inevitably recognise a border that has been imposed by colonial violence – and with it the expulsions of 1948, 1967 and recent decades – and the expropriation of Palestinian property associated with them as irrevocable. Closely linked to this is the appropriation of water, agricultural land and other natural resources through settler colonialism and the control of external borders.

Today’s reality is the existence of a single sovereign state (Israel) that categorically excludes a true division of its sovereignty (with the Palestinians). It is a utopia to tame this state in such a way that there is room for a second one next to it. The prerequisite for any just solution is its revolutionary smashing and the creation of a new bi-national state.

Although Marxists demand the right of secession and a state of their own for oppressed nations, this demand cannot be made indiscriminately, without taking into account the specific circumstances of oppression.

A Palestinian ‘state’ alongside Israel would not only legitimise past injustices, but would also have to accept as definitive the ethnic cleansing currently taking place in the West Bank. The establishment of a border between the two states would most likely lead to a new wave of expulsions of as many Palestinians as possible from the 1948 borders. Such scenarios are advocated by, among others, the ultra-right Zionist party Yisra’el Beitenu (Our Home Israel).

The reactionary content of the ‘two-state’ idea is made clear by the fact that its ultimate goal is the creation of an ethnically homogeneous state of Israel, i.e. the completion of the historic mission of settler colonialism – albeit with the necessary modification of the ‘two-state’ concept: a slightly reduced territory. As long as the existence of a settler state based on ethnic exclusivity is accepted, the historic purpose of the two-state solution can only be to complete it – regardless of what hopes some Palestinians may associate with the prospect of a state of their own alongside Israel.

A Palestinian state that is somehow conceivable under today’s conditions – deprived of its state sovereignty and the most important social question, the right of return – would not solve the Palestinian question, but endow oppression with comprehensive political legitimacy. Such a ‘deal’ would also build on the ‘normalisation’ of Israel through the Abraham Accords of 2020. In the worst-case scenario, the Egyptian regime could be forced to agree to the expulsion of Palestinians from Gaza and their settlement in Sinai.

Revolutionaries should therefore unequivocally advocate a ‘one-state solution’. Of course this position also entails the question of the class character of the state to be fought for. Creating a fair balance between both nationalities requires the massive transfer of resources to compensate and resettle the displaced. The elimination of the apartheid character, which has already been concretised in urban planning and roads, is only possible on the basis of communal ownership of land, housing, industry and mineral resources.

It thus falls to the working class, which would expropriate these resources and make them accessible to the democratic planning of a bi-national state. The linking of the democratic revolution with the socialist revolution therefore constitutes the programmatic core of the revolutionary strategy for the liberation of Palestine: permanent revolution.