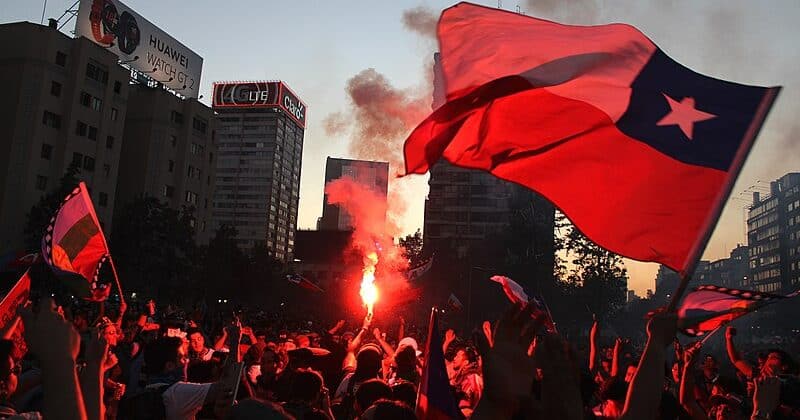

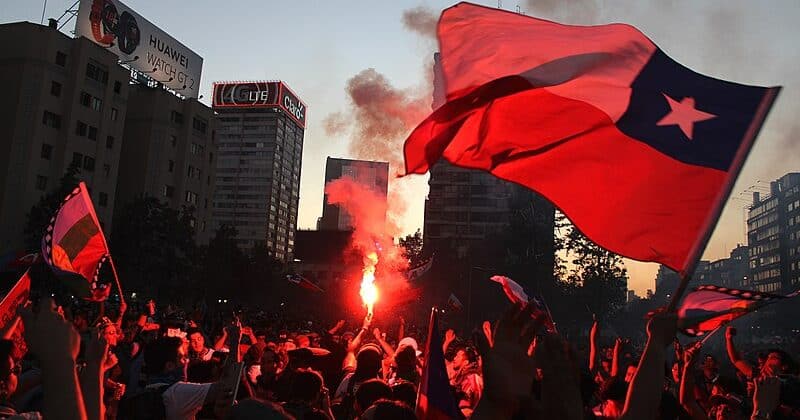

Last year the masses in Chile waged a heroic struggle against the ruling class, forcing them to grant democratic and economic reforms in an attempt to placate the movement. A year later, on the 19th of October, the Chilean people returned to the streets to show the elites that the movement continues. Then, on the 25th, in a referendum conceded by the government, the population overwhelmingly voted to rewrite the old constitution by setting up a constitutional convention of 155 citizens. With a 90% turnout, nearly 80% voted in favour of removing the old 1980 constitution that was put in place by Chile’s brutal dictator, Augusto Pinochet.

2019: When “Chile woke up”

Just over a year ago the Chilean ruling class was touting the nation as a beacon of stability and success, being the wealthiest nation per capita in South America. But this was not the Chile experienced by the vast majority of ordinary people. Chile is the most unequal nation in South America with over a third of those who live in cities suffering extreme poverty. A small rise in subway fares was all it took to ignite the powder keg and engulf the country in weeks of unrest in 2019, with huge demonstrations, growing strikes and daily clashes with the security forces. The country saw some of its largest ever demonstrations, and a strike movement of miners, dockworkers, truck and bus drivers forced the union leaders into calling general strikes that forced the previously intransigent government into desperately offering reforms to save their administration.

Before conceding reforms, the government had tried to repress and defeat the movement. They deployed the police in vast numbers and unleashed the hated national police, the carabineros, to brutalise protesters. They eventually even sent the military onto the streets for the first time since the dictatorship. The result was 30 dead, hundreds blinded and seriously injured, and thousands arrested, 2500 of which would still remain in jail 6 months later. But all this repression did not silence the masses, the demonstrations became increasingly militant. Protesters used inventive methods to combat the militarised riot police such as the mass use of laser pointers to impede the use of riot helmets, armoured vehicles and helicopters. But more significantly the growing strike wave and, alongside it, the beginnings of a popular, working class democracy forming in grass roots assemblies to coordinate the movement, panicked the government and forced them to accept that the movement could not be repressed.

Firstly, the right-wing government of billionaire Sebastian Piñera offered major economic reforms including an increase in wages, taxes on the rich and an increase in the miserably low pension. But this was not enough: the general strike was escalating alongside calls for the fall of the government. The ruling class and political parties (including the principal parties that claim to represent the working class such as Frente Amplio and the Communist Party) closed ranks and offered a way out by attempting to limit the movement to calling for a constituent assembly to rewrite the constitution.

After these concessions and after weeks of repression the demonstrations still continued, but on a smaller scale. When the pandemic hit, the movement largely fell silent. The ruling class no doubt tentatively breathed a sigh of relief. But this respite was short lived as the pandemic fed into the economic crisis whilst exposing the inequalities and inadequacies of health care and capitalism generally, exacerbating the conditions that caused the initial rebellion.

Beyond the constituent assembly

In a country of 19 million, coronavirus has killed 18,000, including over 3,500 who received no medical treatment. Alongside this, poverty has reached levels not seen since the economic depression of the early 80s, and around a third of the population is unemployed or underemployed. It comes as no surprise then that strikes and protests, including by the indigenous Mapuche population, have picked up again over past few months. The government tried to crush these, aided by repressive laws (such as allowing for the mobilisation of military outside of martial law) that they have been preparing, with the support of political parties including Frente Amplio, in the interceding months. But this, including the much-publicised hospitalisation by police of 16-year-old Anthony Araya, have only added fuel to the fire, resulting in the massive turnout for the demonstration on 19October.

The continuation of the movement, both in the streets and in the workplaces, schools and universities is imperative if the movement is to achieve any lasting change. The winning of the referendum to set up a constitutional convention is undoubtedly a step in the right direction, a forcing of the ruling class to make a huge democratic concession. But alone it represents a dead end. Firstly the process is full of pitfalls and obstacles meant to dampen its effectiveness in truly representing the will of the people, it is based on the same undemocratic electoral process as the election of parliament, it is a slow process (already postponed) that is meant to drag out until 2022 at the earliest, but more significantly it is shackled with a policy of only allowing decisions to be passed with 2/3rds majority, a rule that will blunt its radicalism.

But more fundamentally, even a body as democratic as a constituent convention or assembly exists within the confines of the undemocratic capitalism system. A system dominated by a tiny group of rich people (the top 1% own 26% of the wealth) who, through their exploitation of the population, possess all the wealth and economic power in society and who have used this might to build up a powerful state that serves their interests and enforces their will through via a brutal police force and military hierarchy.

Socialists should absolutely campaign for the new constitution to be as radical as possible, fighting for the recognition of indigenous rights, the expropriation without compensation of major industry, the ownership of land to those who work it and the breakup of the police and their replacement with democratic militias made up of working people. But any illusion that a convention can impose these demands, let alone expect a capitalist government to implement them is a deadly mistake.

Any attempt to impose such radical measures will be met with sabotage and ultimately violence by the ruling class and their state. This is the overwhelming lesson of the experience of the 1970s in Chile. At that time Salvador Allende, a self-declared Marxist, was elected as President of the country and yet his entire administration was attacked, disrupted and sabotaged by Chile’s ruling class, backed by their imperialist masters abroad. When this failed to crush the movement, they backed a coup led by the brutal General Pinochet (Allende’s own defence minister) who drowned the revolution in blood.

The lessons of the past cannot be forgotten, the constitutional convention can provide a platform to popularise ideas of what the new Chile should look like but the only way to make the changes necessary to win a dignified life for the majority of people in Chile is ultimately through a revolution. To do this it is necessary to warn of the dangers of putting any faith in the democratic goodwill of the ruling class, instead a separate, rival democracy must be built among the masses, like the one that was forming during the protests last year. This democracy, made up of mass assemblies of the working class, poor people and the rank and file of the military, rooted in the workplaces, schools and neighbourhoods can act as a separate pole of power that can fight for the reins of power, spread the movement to the working people of other countries and enact the changes necessary to end capitalism and its inevitable symptoms of poverty, war, exploitation and oppression.

Books & Magazines for sale from Red Flag: