By Alex Rutherford

Zionism was born in Central Europe, in response to the oppression and violence faced by Jewish people in countries like Germany, France and Russia. It is a tragic irony that Zionism, which emerged as a response to racist persecution, has turned itself into a racist ideology in order to justify creating a modern Jewish nation by expelling the inhabitants of Palestine from their homeland. Of course, this was not a unique phenomenon, nearly all the European settler projects of the 18th to 20th centuries did the same thing, treating those they displaced as inferior beings.

Antisemitism

Zionism emerged as a reaction to the rise antisemitism in European countries. Its ideological founder and organiser, Theodor Herzl, (1860-1904) claimed in his memoirs that it was his presence in Paris in 1894 during the Dreyfus case (A Jewish French officer falsely accused of spying for Germany) and hearing crowds shouting, “Death to the Jews!” that convinced him that the antisemites were right about one thing; that Jewish people could never successfully assimilate.

At the same time, Herzl witnessed with approval the expansion of European empires. Many established settler colonies for their “surplus” population—the French in Algeria, the British in South and East Africa as well as Australia. In 1896, he published The Jewish State which argued that Jews should leave European countries and found a colony to develop a “normal” national life. He went on to found the Zionist Movement with its regular congresses and sought out leaders like Kaiser Wilhelm II and Tsar Nicholas II, who were notorious antisemites. This foreshadowed later Zionist leaders’ attempts to gain the support of antisemitic rulers, most startlingly Adolf Hitler.

Most Ashkenazi Jews from Tsarist Russia, faced with the wave of pogroms, preferred to emigrate to western Europe or the USA while, amongst those who remained, a majority turned to socialism joining either the Jewish Socialist Bund or the Social Democrats. A minority, however, formed what became known Labour Zionism. A key figure was Ber Borochov, who founded Poale Zion (Workers’ Zion) arguing that to become a “normal” nation, settlers had to develop a rural and factory proletariat and ensure that Arab workers and peasants had no place in their economy. Out of this developed the slogan “the conquest of labour”, “Arabs” were displaced from the farms and factories where they worked. The main instrument for this conquest of labour was a “trade union”, the Histadrut, founded in 1920. Labour Zionism, under the formidable David Ben Gurion, became the main instrument in the settlement project.

Imperialism

Herzl’s successor, Chaim Weizmann, was the one who struck lucky in his search for an imperial sponsor of the colonisation project. Leading British parliamentarians such as the Liberal David Lloyd George and the Conservative Arthur Balfour, saw that Zionist colonising would suit Britain’s post war strategic interest—creating “a little loyal Jewish Ulster”, as Britain’s first Governor of Jerusalem, Ronald Storrs, put it.

This resulted in the famous Balfour Declaration of 1917, which promised the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine. It also stated that nothing should be done which might prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, whose Jewish population was only around 5 percent at this time. Lloyd George, later cynically remarked, “During the world war (we) gave Arabs and Jews conflicting assurances. We sold the same horse twice.”

In the British League of Nations Mandate, the British tried to play the Arabs and Zionists against one another. Although the Palestinians soon realised that they had been denied self-determination, the Zionists were outraged when the British imposed quotas for Jewish immigration to placate the Arab ruling classes across the region. Jewish immigration remained relatively small-scale until the rise of the Nazis led to a wave of Jewish migration from Germany. Some 150,000 new Jewish immigrants came to Palestine in the two years after Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933. This brought the Jewish population up to 443,000, or 27 percent.

Early in the Nazi regime, German Zionist leaders made the “Haavara Agreement” to allow German Jewish emigrants to Palestine, who would then use their liquidated assets to turn Palestine into an export market for German products. The influence of Zionists in the USA also undermined the campaign there for a boycott of German goods. A minority within the Zionist movement, led by Ze’ev Jabotinsky, actually built links with Mussolini’s fascist regime in Italy, although Jabotinsky eventually changed course and helped form a Jewish Legion, which served in the British Army.

In the 1930s, conflict began to increase between Jewish settlers and the Arab population, leading to the Arab revolt in 1936. Many tactics used by the British in suppressing the revolt, including house demolitions, and imposing fines on whole villages with collective punishment, echo Israel’s tactics today. The uprising lasted until 1939, and its defeat was one of the defining tragedies of modern Palestinian history.

With the approach of war, Britain had to make a turn towards the Arab leaders in Palestine and puppet monarchs in Transjordan and Egypt, promising them independence once the upcoming war was open and straining relations with the Zionist leaders. Nevertheless, when the war broke out, the majority of the settlers under the Labour Zionists supported Britain, as did Jabotinsky’s Revisionists. However, a minority, under Avraham Stern’s Lehi, conducted a terrorist campaign against both British and Arab targets.

From 1939, with the conquest of two thirds of Poland, three million Jews fell into Nazi hands and were herded into ghettos in the major cities. Then, between 1941 and 1945, six million of Europe’s Jews perished in the death camps.

After the end of the Second World War in Europe, Lehi were joined in their armed campaign to coerce Britain into accepting a Jewish state in the whole of Palestine by the more “mainstream” right-wing Irgun. By far the most famous of the attacks was the King David Hotel bombing in Jerusalem in July 1946, which killed 91 people including 41 Arabs, 28 British government employees and 17 Jews.

The Nakba 1948

After the end of the war, the conflict between Zionists and Palestinians increased dramatically. Prioritising the need to hold on to Egypt, the Suez Canal and Iraqi oil, Attlee’s Labour Government decided to wash their hands of Palestine, surrendering their “mandate” to the newly established United Nations.

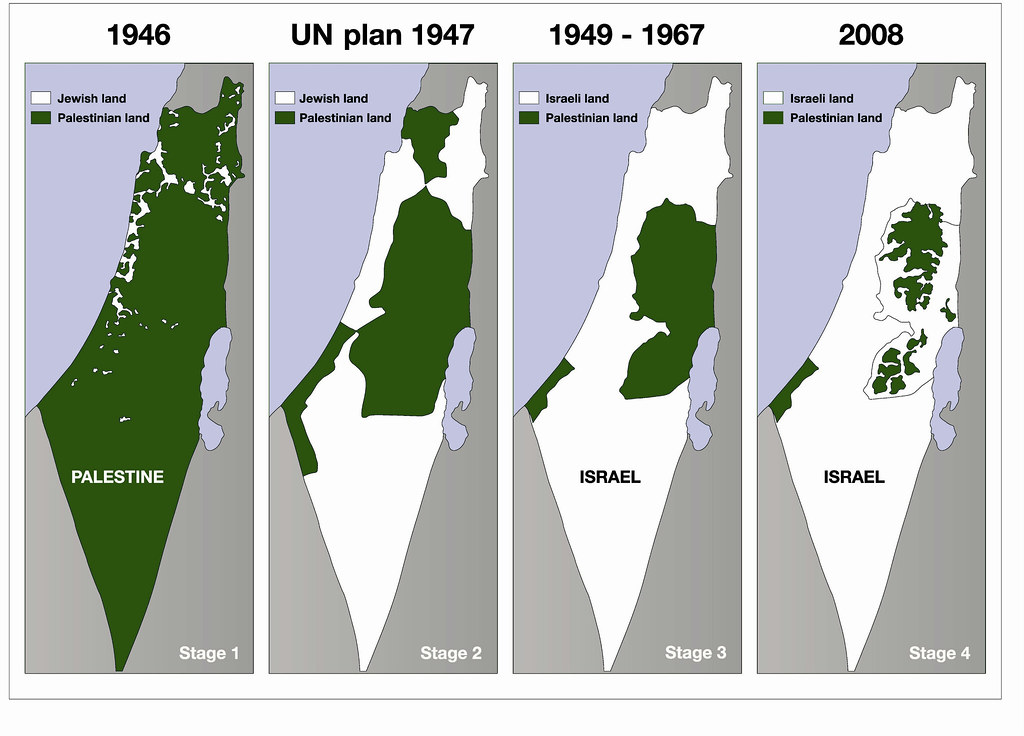

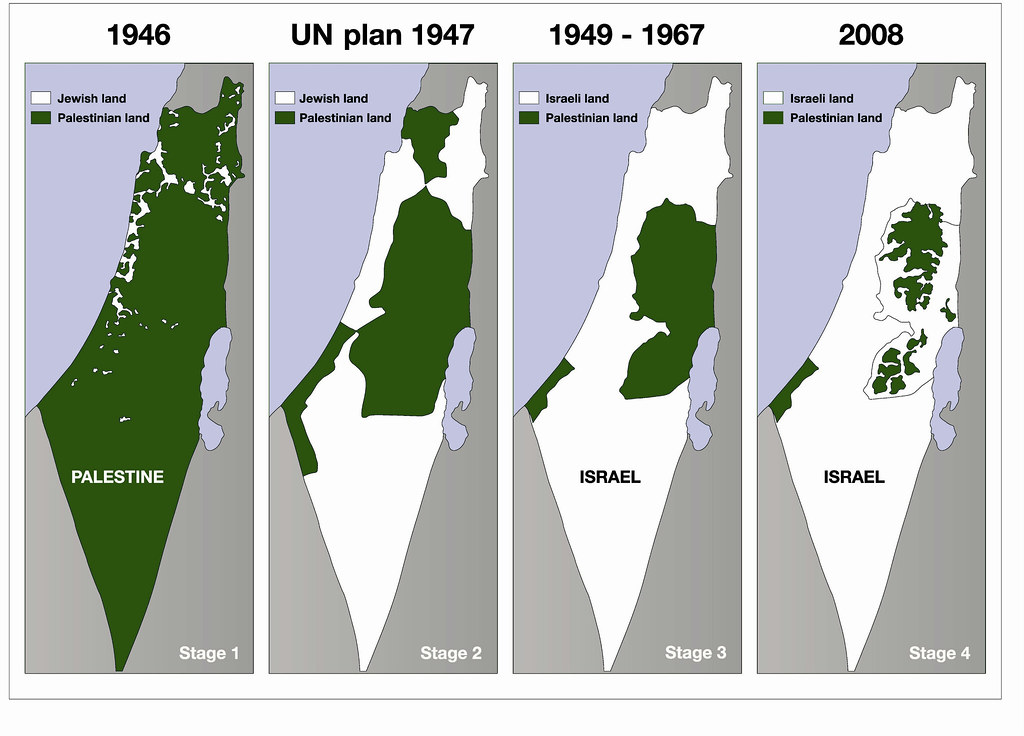

This opened the space for the new Israeli state’s well-armed and well trained militias to seize 78% of the former British mandate territory, despite having been awarded only 56% in the UN’s “partition plan”. The myth that the huge armies of the Arab states fell upon “poor little Israel” has been thoroughly exposed by anti-Zionist Jewish and Israeli historians like Ilan Pappé.

The Arab states were all under either French or British hegemony and limited their “invasion” to occupying what became known as the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The Palestinian militias had very few arms and nothing like the training the British had give the Zionist militias who had supported their war effort. British troops refused to intervene to protect Arab villagers being ethnically cleansed by the Zionist forces.

Soon, some 530 Arab villages were destroyed or emptied of their residents, as well as the Arab quarters of all major urban areas, most notably 120,000 inhabitants of the port of Jaffa. These atrocities were calculated to spread panic and induce the indigenous population to flee. The most infamous of the estimated 110 massacres carried out by Zionist forces took place at the village of Deir Yassin. This massacre was used to terrify other villages and city districts, as Arabs were urged to flee to avoid a similar fate. An estimated 8,000-15,000 Arabs were killed at this time.

In events that became known as the Nakba (‘Catastrophe’) an estimated 700,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled, setting the tone for the occupation and attempted genocide of the Palestinian people. This poisonous legacy can be seen in Netanyahu’s recent boast that the war in Gaza is Israel’s second “War of Independence”, the name Israel gives to the Nakba.

Since the time of the Nakba, Israel has continued to expand into former Palestinian territory, as well as annexing areas of the surrounding Arab States. Following the Six Day War with Egypt, Syria and Jordan in June 1967, Israel was able to annex more territory, including the Sinai Peninsula, the Golan Heights, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem the settlement process continues unabated. The occupation of Gaza and the West Bank by Israel has resulted in the further suffocation of the Palestinian nation and has increased the divisions between them in terms of status and rights.

This history reveals that Zionism is not, as some claim, simply “Jewish nationalism”, an entitlement to self-determination in their supposed historic homeland, but a colonial settler project inseparably linked to expelling the country’s majority nationality. As such, the rights of its Jewish citizens cannot be at the expense of the Palestinians. They must agree to share the country with the Palestinians already living there and those in the Diaspora who wish to return. Such a state can assure both communities, and those of all religions and none, of equal rights and the development of their languages and cultures.

As we argue elsewhere, this goal will only be realised if the working class, Jewish and “Arab” comes to the head of a struggle to demolish the apartheid-like structure of the Zionist settler state. This will necessitate the socialisation and planning of the economy so that workers of both national communities can live and work alongside one another and can only be built at the expense of Zionist capital and its imperialist backers.