By Markus Lehner

IN THE debate about the Ukraine war, the question whether the Russian Federation is an imperialist power plays a central role. Long before this war, we analysed Russia as a newly established imperialism, in contrast to currents such as the Trotskyist Faction (FT–CI) and most post-Stalinist groups.

Left wing critics of our characterisation usually rely on Lenin’s ‘five basic features’ in his pamphlet, ‘Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism’. For example, Russia’s negative balance-sheet in terms of direct investment and its dependence on the export of raw materials rather than the strength of its finance capitalist monopolies are often used as ‘proof’ that it cannot be considered an imperialist power.

Lenin’s imperialism

First of all, it is important to counter the misinterpretation of Lenin’s concept of imperialism. The repeatedly cited ‘five criteria’ are actually explained as characterising the current stage of development of capitalism as a whole, as a global system, not the character of any particular state.

Moreover, Lenin speaks of the ‘characteristics’ that a correct definition of imperialism must include, not of some kind of immutable definition. Indeed he immediately adds that, ‘imperialism can and must be defined differently if we bear in mind not only the purely economic aspects’. He also emphasises that the shortest definition is that imperialism represents the monopolist stage of capitalism as a world system.

This clearly means that, in this epoch, capitalism has become the totality of the world economy, there are no longer any non-capitalist niches that are not ultimately determined by the overarching laws of capital valorisation. Also the concentration/centralisation of capital has a modifying effect on the tendencies to equalise the rates of profit to the average rate of profit.

This means that a certain combination of finance capital, industrial capital and state agencies is able to secure its own profitability and stability at the expense of other capitals and states, albeit temporarily because there is no absolute monopoly and monopoly profit rates ultimately cannot be decoupled from the general valorisation problems of capital.

This economic basis then leads to Lenin’s characteristics: the importance of capital export in the system as a whole stems from the problem of over-accumulation in the imperialist centres, which is overcome by investing surplus capital in countries where the lack of equalisation of the international rate of profit creates more favourable investment opportunities (e.g. through cheaper labour and raw materials).

Thus, the export of capital is not a defining element ‘in itself’, but is inevitable for those imperialist capitals whose falling profit rates are already accompanied by over-accumulation (i.e. their own growth and export of goods no longer offer sufficient profit prospects for investment capital).

The decisive factor for Lenin, however, is that monopoly has led to a division of the world economy among large capital associations. This allows for new divisions, let alone new players, only within very narrow limits. Anything on a larger scale would necessarily mean violent shocks, analogous to an earthquake. This division of the world economy cannot find a political counterpart in the form of a bourgeois nation-state and can only be stabilised by a system of imperialist Great Powers.

Russia

The development of the world economy thus goes hand in hand with its political division into spheres of influence of the Great Powers. This explains why Lenin analysed Tsarist Russia as an imperialist power, although in his time it did not meet the ‘five criteria’. In terms of capital concentration, the importance of its industrial and finance capital and the inflow of capital rather than its export, for example, it was far behind the other imperialist powers.

Although there was a dynamic development in certain industrial sectors and even an incipient expansion of Russian capital, including outwards, the decisive factor was Russia’s military strength as an expansive Great Power, which was itself associated with this still subordinate economic dynamic. In Central Asia and parts of Europe, this led to a role comparable to the colonialism of the other major European powers in the overall imperialist system before the First World War.

Contemporary Russia is also marked by such contradictory tendencies. After the collapse of Stalinism, in the turbulence of the restoration of capitalism in the 1990s, many production facilities were destroyed while others expanded, all to the benefit and enormous enrichment of a small layer of managers and finance capitalists. In this phase, a sell-off of Russia to Western capital could well have happened, but was avoided because of the high risks, especially after the economic collapse in 1998, the ‘Russian crisis’.

Commodities and capital

Under Putin, in the 2000s, there was some renationalisation, or at least the securing of blocking minority shareholdings by the state, without fundamentally overcoming the system of oligarchs. As a result, the raw materials and energy sectors in particular became a stabilising factor in Russian capitalism, beyond the influence of Western capital.

Since then, Russia’s trade balance has consistently shown not only positive surpluses, but exports systematically exceeding imports, by a third on average. This applies not only to oil, coal, gas and grain, but also to strategically important raw materials. These include copper, nickel, uranium (with Kazakhstan dependent on Russia), palladium, aluminium, gold, diamonds, timber. Russia was not only able to accumulate considerable wealth through this abundance of raw materials, independent of any foreign monopolies, but also to gain a strong degree of economic self-sufficiency.

Given the state’s reserves and its shareholdings, it is not surprising that the Russian state is one of the least indebted in the world. For example, the proportion of public debt to GDP was 19% in 2020, compared to 133% for the US.

In the slipstream of this stabilisation, strategic industries in the IT sector, mechanical engineering and high technology were able to maintain strong and dynamic growth. This corresponds to the great importance of the military-industrial complex in Russia. Even before the Ukraine conflict, more than 4% of GDP was regularly spent on arms and Russia is one of the world’s largest arms exporters. This also had an impact on the overall growth rates of the Russian economy. After the United States, the Russian Federation is the second largest military power in the world.

Finance capital

Finance capital in the Russian Federation is also considerable. Banks such as Sberbank or VTB are sufficiently large for the needs of Russian capital for domestic and foreign business. In addition, there are fund companies that originated in the energy and commodities sectors and can now operate with huge sums of money, such as the ‘National Wealth Fund’ or the ‘Russian Direct Investment Fund’. In the meantime, there are joint investment funds with China, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait and some other countries, which create ever greater scope for Russian finance capital (even after Western sanctions).

The Russian Federation has also established a wide range of regions of the world into which its direct investments can flow. The pressure on the Russian economy in terms of necessary foreign investment is not as great as that of other imperialist countries since, on the one hand, it has its own cheap labour market for a growing economy and, on the other, it is sufficiently compensated by energy, raw material and arms exports. The former Soviet republics in Central Asia represent a large area for secured investments as well as for easily exploitable ‘labour power resources’.

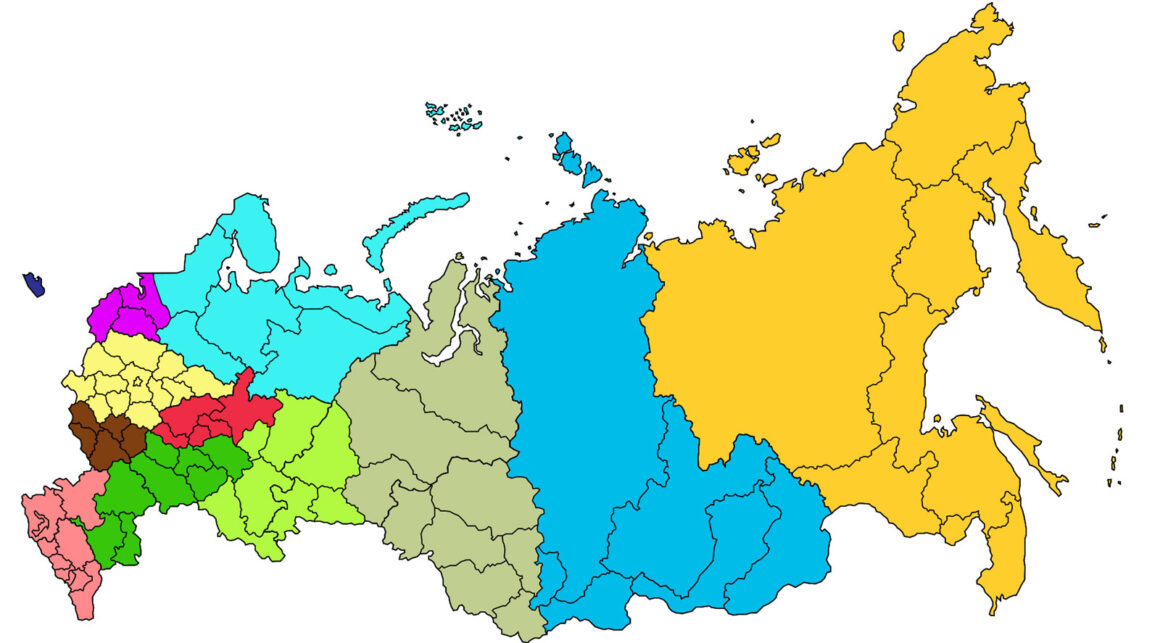

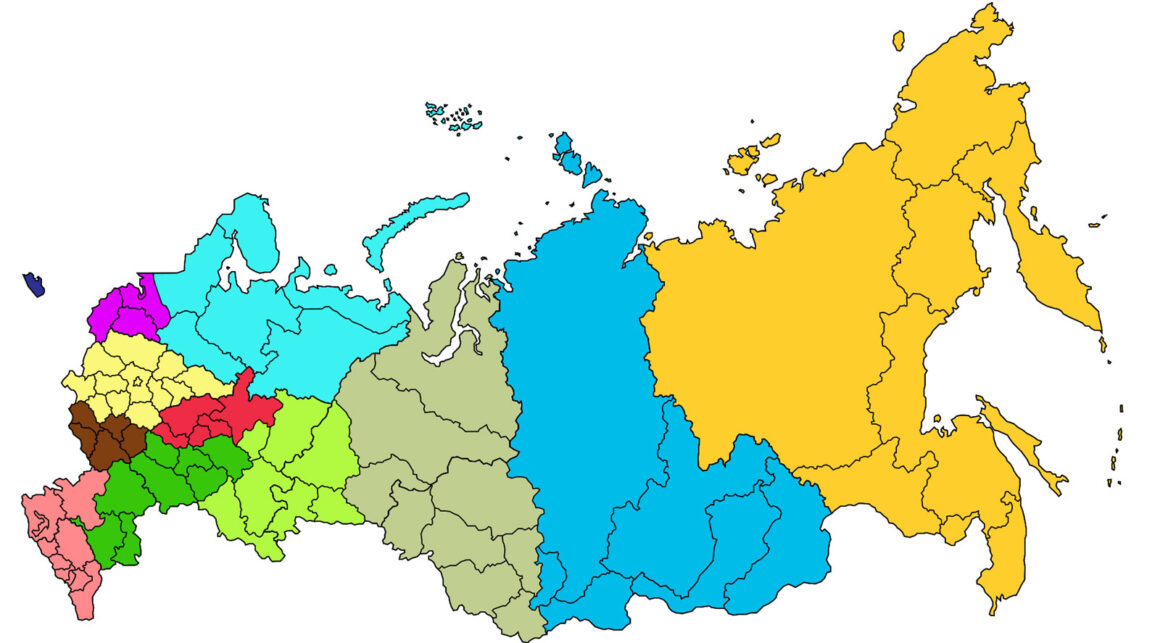

Russia is a post-colonial power, with a huge racially and nationally oppressed ‘non-Russian’ population. Migrants or colonised ethnicities form a large portion of the lower echelons of employment. The brutal war in Chechnya was a major factor in the authoritarian fortification of the internal colonies in the Russian ‘Federation’. It also played a preparatory role in the general turn to authoritarianism through the development of appropriate security structures in connection with this Russian variant of the ‘war on terror’.

In addition to Central Asia and the Middle East, Russian direct investment in Africa and Latin America (often in conjunction with the arms industry) has also risen sharply in recent years. Since 2016 and sharply declining capital flows from the West, Russia has also shown a positive balance in terms of direct investment. In 2018, new foreign direct investment fell to $8.9 billion, compared to an increase in Russian direct investment of $28 billion abroad.

It should also be noted that, until recently, the largest Western direct investor in the Russian Federation was the Republic of Cyprus (2020: $147 billion in existing investments). However, most of this capital can be traced back to Russia itself (2020: FDIs amounting to $193 billion from Russia). This is probably because many Russian capitalists have limited trust in their own state and were attracted by the tax advantages and banking policy in Cyprus, from where they made their investments in Russia.

At the same time, Cyprus has granted generous schemes for dual citizenship with appropriate investments. Counting the Cypriot billions, Russia was already a net exporter of capital, rather than an importer, in the 2010s. The ability of Russian capital to compensate for the massive halt in capital inflows due to Western sanctions following the attack on Ukraine shows how little Russia resembles a semi-colony that would not survive economically even for a month after such sanctions.

Class structure

Russia, as the largest country with the second largest army in the world, as one of the largest global suppliers of raw materials and energy, with very large monopolies and finance capitals based on it, is certainly nobody’s ‘semi-colony’. The relatively large role of the state in financial and monopoly capital, as well as the comparatively high criminal streak in domestic big business, however, is certainly a sign of its weakness.

In the context of catch-up development and due to its origin in a former degenerated workers’ state, Russian capitalism still has characteristics of ‘primitive accumulation’ in many areas, in which the state and mafia-like relations of exploitation play a relatively large role. This also means that an independent middle class has not yet emerged on a large scale and that there is a relatively large gap between the super-rich and the mass of the population.

Russian imperialism, therefore, lacks the social base of a large labour aristocracy and middle class for a stable parliamentary regime, as exists in the West. That explains the Bonapartist Putin regime, which suppresses any form of consistent representation of the interests of workers and peasants or contains them through nationalist populism.

Unlike Western imperialism, it cannot sell itself as a ‘stronghold of democracy and human rights’, but must repeatedly resort to direct military threats or violence in its global action, instead of ‘soft power’ and credit. Russian imperialism is therefore still struggling for recognition and a global role. In many respects it remains in a weaker position vis-à-vis the established imperialist powers, which it has to overcome by military-political means.

Great Power role

Thus, the crucial question for the imperialist character of Russia is the role it plays in the concert of the Great Powers and in the current struggle for the redivision of the world. During the consolidation of Russian capitalism in the 2000s, its return to the global stage was made possible mainly through a kind of deal with the leading European powers. As an essential supplier of energy and raw materials for European production chains, especially for Germany and France, its special role as a military-political superpower in competition with the USA was also accepted. This initially affected mainly Central Asia, but later also Africa and especially the Middle East, e.g. Syria.

There have been tendencies in the EU to work with Russia to counterbalance the looming confrontation between the US and China. Until about 2014, the stabilisation of Europe’s core economies in the globalisation period was closely linked to Russia’s economic and political resurgence. However, it soon became apparent that this ‘partnership’ was bringing growing conflicts of interest.

While some Eastern European EU countries vehemently favoured an ‘Atlantic partnership’ anyway or propagated Nato’s eastward expansion, in Georgia, Moldova, Belarus and, above all, Ukraine, the respective influences and interest groups met with more and more mutual contradictions. Ultimately the US did everything in its power to win over the EU imperialisms unequivocally to its side in its main confrontation with China and to detach a manoeuvring EU from its ties with Russia.

Russia was still able to achieve military-political successes in Georgia and Syria and established itself as a ‘gendarme’ through minor interventions in Central Asian crises, within the framework of the CSTO ‘security alliance’. The EU, however, could not simply let Russia and its local allies have their way in Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine without losing its credibility in Eastern Europe.

Importance of Ukraine

The Ukraine war once again shows the fundamentally rotten character of imperialism. Contrary to how it is portrayed in the ‘West’, for the US and the EU it is not about ‘democracy’ and ‘unlawful annexation raids’, but about the struggle between imperialist powers. Even if the Western narrative of ‘spheres of influence’ is declared to be a concept from the last century, a long-term weakening of an imperialist rival in Eastern Europe and a safeguarding of their spheres of influence right up to its borders are of course matters close to the hearts of the US and the EU.

Russian imperialism is trying to secure its ‘traditional sphere of influence’ because Ukraine was, and could be again an important part of Russian monopoly capital, industrially, agriculturally and in terms of raw materials. Russian-speaking minorities or historical connections have been, or are being exploited to build up appropriate pressure and find pretexts. Since Russia lacks the economic and ideological means (‘democracy!’), the only thing left for it is to use its military strength to secure its sphere of influence.

Since independence, Ukraine’s rulers have tried to manoeuvre between the two imperialist camps, now in the direction of the EU and Nato, then in the direction of Moscow. With the Maidan coup in 2014, this phase was over. While a majority of Ukrainians certainly have illusions in a democratic and independent Ukraine, those forces that ultimately and objectively make the country a semi-colony of Western imperialism have prevailed in Ukrainian politics.

This has become very clear economically, quite simply, through the IMF programmes since then and the resulting ‘liberalisations’, sell-off plans and ‘reform projects’ (especially in the area of labour law). The complete dependence of Ukraine’s defence capability on Western arms and ammunition deliveries, as well as on training, reconnaissance and IT infrastructure services (especially from the US) show its emerging character as a highly armed semi-colony.

The Ukrainians thus became pawns in the imperialists’ struggle for spheres of influence. While their struggle for self-determination and defence against Russian aggression is more than justified, their struggle for a truly independent Ukraine cannot end with the repulsion of the Russian invasion. For the mass of Ukrainians, the following invasion of the Western ‘friends of freedom’, disguised as ‘reconstruction aid’, will be the next stage in their struggle for independence, this time on the economic level.

A new Russian revolution

By intervening in the Ukraine conflict, annexing Crimea and ultimately the 2022 invasion, Russia has exposed its character as the weakest link in the chorus of major imperialist powers – any other explanation would only reinforce the Western narrative of the invasion as the work of ‘Putin gone mad’. The development of the war since then also confirms this.

On the one hand, the Russian army was not strong enough to win a decisive victory against a Ukrainian army that was highly armed by the West and highly motivated in its justified will to defend itself. On the other, despite massive economic sanctions, Russia has been able to switch to a war economy that is conceivably able to sustain a war of attrition in the longer term, which could ultimately become too costly for Western economies as suppliers to Ukraine.

The future course of the Ukraine war will also be decisive for further developments in Russia. The economic and human consequences of the war are becoming increasingly difficult to bear. Even if the Russian economy has so far been able to prevent collapse, it is becoming more and more dependent on the support of ‘friendly’ powers. So far China, in particular, continues to rely on an outcome that guarantees Russia certain profits and in any case does not lead to the collapse of the current regime. A collapse could lead to a radicalisation of the prevailing nationalist policy to save the interests of Russian monopoly capitalism.

Given the weakness of the liberal, but above all the left wing opposition and the lack of militant organisations of the working class, this is quite likely. At the moment, because they misunderstand the real essence of fascism, many are already calling the current regime fascist. However, dissatisfaction with the course of the war could lead to a cruel form of real, revanchist Russian fascism, leading to a new stage of militarism and military aggression by this nuclear power.

In this respect, it is absolutely necessary for leftists in Russia and their supporters in the West both to clearly demonstrate the imperialist character of Russian politics and economics and to get to the root of this evil, namely by smashing Russian capitalism and its state apparatus — through a new October Revolution.