The Court of Appeal has overturned convictions against the Shrewsbury pickets, after a campaign by workers and unions lasting almost 50 years.

The Shrewsbury 24 were arrested during the building strikes of 1972, when over 300,000 workers launched a national three-month strike to demand a 35-hour working week, a base wage of £30 per week and the end of casualised contracts.

Organised by rank-and-file militants around The Building Workers Charter, strikes often went ahead against the wishes of the trade union and Communist Party bureaucracies. Flying pickets of vans of strikers visited building sites in North Wales and Shropshire to prevent strikebreaking.

Almost half a year after the end of the 1972 strike, 24 pickets were arrested and charged with over 200 offences including unlawful assembly and affray. In October 1973, after a year of punitive bail conditions, all those charged were found guilty. Six were sent to prison.

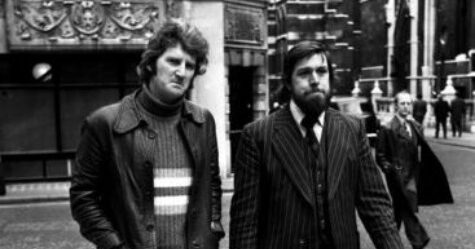

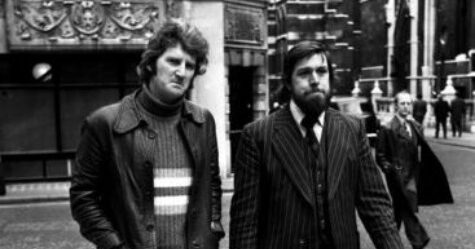

Actor Ricky Tomlinson, then a plasterer, was one of those sent down. He was convicted of ‘conspiracy to intimidate’ along with Des Warren, now deceased. Tomlinson and Warren received sentences of two and three years respectively.

Half a century later, and after a sustained campaign by rank-and-file trade unionists, three judges have quashed the convictions. The decision has wide-ranging implications for the labour movement, and sets a positive legal precedent for other victims of political trials and policing, such as the Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign.

News of the Court of Appeal decision comes days after Conservative peer Norman Tebbit, Secretary of State in the Thatcher Government, admitted to instructing Special Branch to spy on trade union activists. In a strange display of Tory indifference, Tebbit made the admission during a Zoom call organised by Labour MP Richard Burgon to discuss the ongoing inquiry into undercover policing.

Attendees at the online meeting were shocked by Tebbit’s admission that he received regular briefs from senior Special Branch officers on trade union activities. His admission reveals a long-known truth in the labour movement: that the state, with the support of elected governments, spies on —and ultimately works to convict—trade union activists.

Tebbit’s strange intervention shines an unexpected and unintended light on the Shrewsbury 24 victory. Campaigners against undercover policing have long asked how far it went up the chain of command. Tebbit’s admission of the extent of collusion between the state and the bosses is not only revealing, but confirms what many already knew.

“We were brought to trial at the apparent behest of the building industry bosses, the Conservative government, and ably supported by the secret state. This was a political trial not just of me, and the Shrewsbury pickets – but was a trial of the trade union movement,” said Ricky Tomlinson.

The Shrewsbury trials were an attempt by the Heath government and the bosses to shackle an insurgent and increasingly militant rank-and-file trade union movement. Revelations that the Heath government was behind an anti-union TV documentary in 1972 confirms the extent of this.

State repression of left-wing and environmental movements has gained widespread publicity in recent years, much of it around the role of undercover officers in the highly controversial Special Branch Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) in the surveillance and systematic abuse of activists.

Recent court cases have heard that SDS officers Mark Kennedy and Bob Lambert formed long-term relationships with women activists while undercover, and zealously engaged in the psychological, physical and sexual abuse of those around them. Kennedy and Lambert are but two individuals in a long and sorry list of undercover officers involved in similar operations under the direction of top coppers and senior politicians.

Since the ruling, trade union bureaucrats and Labour politicos far and wide have rushed to nostalgise the 1972 strikes, and declaim the values of a united broad left. However, they miss the point. The 1972 building strike shows the power of rank-and-file militancy—and how far the state and the bosses will go to undermine an insurgent rank-and-file movement.

The Court of Appeal ruling is too little, too late. For scores of trade unionists active during the 1972 strike, blacklisting, victimisation and political policing have been disastrous for their lives and careers. And this is a practice that continues to this day, with much more evidence yet to be uncovered. The Shrewsbury 24 have had their long-awaited victory, but this is only one step towards justice for the many victims of state repression.