By Peter Main

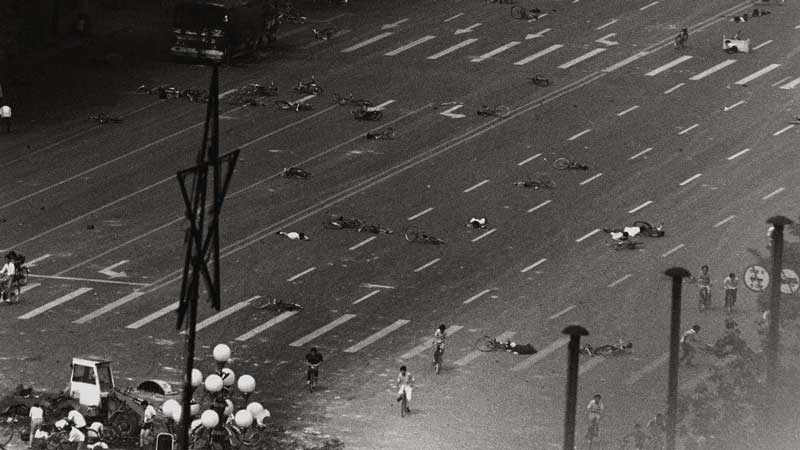

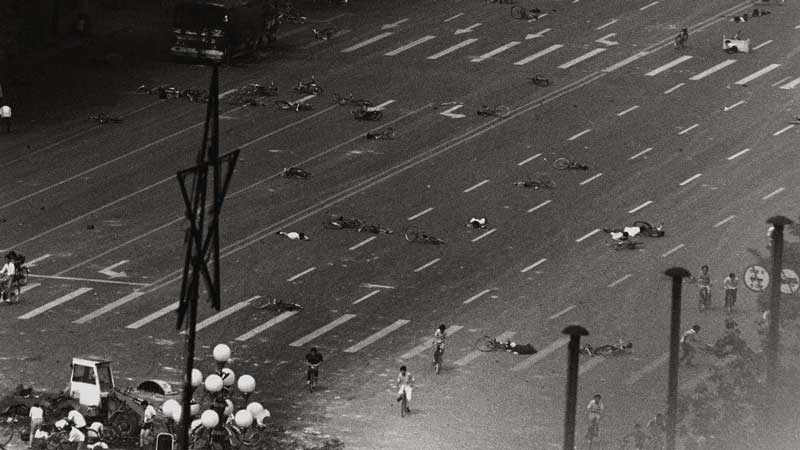

In the early hours of June 4, 1989, tanks and infantry of the People’s Liberation Army advanced into the vast Tiananmen Square which lies in front of Beijing’s “Forbidden City”, the seat of government. The Square itself was occupied by tens of thousands of supporters of the “Democracy Movement”, mainly students, who had been camped there for several weeks. The tanks did not stop their advance, their tracks crushed the tents and all who could not escape, many more died as troops opened fire directly into the crowds.

As news of the Tiananmen Massacre spread, tens of millions mobilised in protests in all the main cities of China, general strikes brought much of the country to a standstill. Martial law, first declared in Beijing on May 18, was extended to the whole of the country and all mobilisations were repressed as ferociously as in the capital. By July, all resistance was ended, what activity remained was limited to hiding activists and trying to document the dead and the missing.

The movement that ended so bloodily echoed the “Democracy Wall” mobilisation of a decade earlier. Like that, it reflected a division in the leadership of the Communist Party of China, CPC, over economic policy. In 1978, the debate ended with the victory of Deng Xiaoping’s proposals to stimulate growth by “market reforms” to the system of state planning. By the mid-80s, however, those had produced contradictory results; the re-introduction of private farming had increased annual production by up to 13 per cent and stimulated the growth of private light industry, but increased managerial autonomy in state industry had not brought any significant development.

The debate over how to resolve this contradiction did not only exercise the leaders of the CPC. In the universities and the ministries, experts, some of whom had been allowed to study in “Western” universities, clashed over the way forward. Such arguments naturally found their way into journals and, thus, into the lecture halls and seminar rooms. Hu Yaobang, the General Secretary of the CPC, encouraged such debates and made it clear that he favoured not only more “marketising” reforms but also a political relaxation.

In January 1987, Hu was replaced by Zhao Ziyang but this did not produce any immediate change in policy. Matters were made worse in September 1988 when the party leadership was unable to agree on price reforms. This paralysis at the highest levels could not be publicly acknowledged, but it was well enough known, especially amongst the intelligentsia.

What brought the issue into the public domain, and gave birth to the Democracy Movement, was the death of Hu Yaobang or, rather, his funeral, in April 1989. As a high ranking Party leader, this was a public event, but one that became an opportunity for demonstrations, especially by students, of support for the man who had championed political debate and even pluralism. Demands were raised for a free press, for action against corrupt officials and for the recognition of independent student organisations. The demos were enthusiastically cheered by the people of Beijing and this, coupled with the official mourning for Hu, ensured no repression.

Emboldened by the experience, the students called a demonstration to commemorate the May Fourth Movement of 1919. Tens of thousands responded and the demo entered Tiananmen Square without the expected official opposition. More, Zhao Ziyang himself publicly declared that much of what the students wanted was in keeping with Party policy.

Nonetheless, nothing actually changed and the students decided to call further demonstrations to greet the Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, on May 15. Gorbachev himself was associated with the introduction of “glasnost” and “perestroika”, openness and reconstruction, in the Soviet Union and the students’ message to the CPC leadership could hardly have been clearer.

So huge were the crowds in Tiananmen Square that Gorbachev had to enter the Forbidden City unseen through a side entrance and it was now that the permanent occupation of the Square began. Hundreds of students began a hunger strike in support of their demands. Three days later, the Standing Committee of the Politburo, the day to day leadership of the Party, rejected Zhao’s proposal for concessions on some of the students’ demands. After he visited the students, he was removed from office and the next day, Li Peng, the Premier, declared martial law in Beijing.

The immediate response, was a massive protest by the people of Beijing. More than a million now occupied the square, strikes paralysed the whole city and prevented trooops from reaching the centre. In the evening, the Beijing Autonomous Workers’ Organisation was founded. For two weeks, the stand-off continued but, away from Beijing, the Democracy Movement was growing in provincial cities and many decided to send delegations of students and workers to the capital.

It was their arrival in Tiananmen Square, coupled with the increasing fraternisation between local garrison troops and the demonstrators, which convinced Deng, the “paramount leader”, that the whole movement had to be stopped, definitively. By the end of May, there was a separate and quite distinct “workers’ section” occupying the north western corner of the square and the first sign of what was to come was the forcible arrest of the leaders of the Autonomous Workers’ Organisation on May 31. Over the next two days, repeated attempts to occupy central Beijing with unarmed troops collapsed in the face of fraternisation. Meanwhile, however, troops from distant provincial garrisons had reached the capital and it was these that were used to clear the Square on the night of June 3-4.

At the time, and ever since, the leaders of the CPC have justified the Tiananmen Massacre as a necessary suppression of a “counter-revolutionary riot”. That it was not a riot is clear from the character of the events, no riot lasts more than a month and involves actions in every major city, but was it counter-revolutionary? For Marxists, and the CPC leaders say they are Marxists, that would mean a conscious attempt to restore capitalism in China, that is to dismantle the planning system, remove the state monopoly of foreign trade and privatise state property.

Not one of those measures figured in the demands of the Democracy Movement, which, instead, focussed on democratic rights; freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, for a pluralist political system, the right to form organisations such as trades unions and student unions. Moreover, far from trying to overthrow the apparatus of the state, the movement limited itself to calling for that apparatus to introduce those rights as reforms. At most, then, this was a mass, radical, democratic protest movement.

With the formation of workers’ organisations, such as the Autonomous Workers’ Organisation in Beijing, the fraternisation with the soldiers and the division within the ruling party leadership, the movement certainly had the potential to develop into a revolution against the party dictatorship, which we would characterise as a political revolution that left intact the existing economic structures. That would have been comparable to the many “people power” revolutions we have seen against dictatorships in capitalist countries, which also did not affect the capitalist character of the economies. However, the movement in China was drowned in blood before it could develop that potential.

What has to be noted is that, in 1992, Deng Xiaoping, the very same “paramount leader” of the CPC, himself proposed the dismantling of the planning system, the setting aside of the state monopoly of foreign trade and the privatisation and trustification of much of state owned industry. In order to allow the new system to work, the regime also removed workers’ rights to jobs, housing, medical insurance and education for their children. Thus, it was the leadership and the apparatus of the Communist Party of China that was the truly counter-revolutionary force and it was only able to complete its retoration of capitalism because in Tiananmen Square it destroyed the ability of the working class to defend itself and its interests.

To this day, the Party will not allow any reconsideration of the events of 1989 and at first sight this might appear odd; the damage done by the “Cultural Revolution” has been criticised and even Mao Zedong is recognised as having “made mistakes”. The point is that those were matters of internal dispute within the bureaucratic apparatus upon which the Party is based and the “reassessments” have been made by the victorious faction. The Democracy Movement was able to grow to a nationwide scale because of the divisions within the bureaucracy but, as a movement, it was a threat to the entire party dictatorship; therefore, anything less than complete condemnation would imply denial of the “leading role of the Party”.

The bureaucratic party’s continued hostility to any democratic limitations on its own power is clear to see from its vicious suppression of national minorities such as the Uighurs of Xinjiang, the steady erosion of civil rights in Hong Kong and the use of the most advanced technologies to monitor the entire population whilst denying it access to information. Those measures themselves virtually guarantee that democratic demands will play a central role in any future mass movement.

There is, though, another lesson to be drawn. The bureaucratic dictatorship restored capitalism in order to preserve its own rule when its control of economic planning brought growth rates close to zero. Just as it had no fundamental commitment to the planned economy, neither has it any to the spontaneous operation of capitalist competition, let alone the democratic political institutions that are sometimes associated with capitalism. This opens the possibility of conflicts of interest between the bureaucracy and the capitalist class that it has brought into existence. Until now, China’s capitalists have been content to put up with bureaucratic rule because it guaranteed profits but, with the emergence of globally significant capital, that could, in time, change.

Under the pressures of slowing economic growth and Trump’s trade war, the assumption that the Party is the guarantor of social stability will be put in question, even by those who have profited from it in the past. In such a scenario, the labour movement, which already exists but is denied any rights, should throw its huge social weight into the struggle for democratic demands. As in 1989, such a movement could grow on a national scale very quickly, its victory will be dependent on the working class forming its own organisations, above all, a political party independent of all factions of the bureaucracy and all currents within the capitalist class. Its goal should be the overthrow of the whole system of bureaucratic dictatorship and its replacement by a workers’ government, based on, and accountable to, the fighting organisations of the working class.