By Andy Yorke

ON 15 APRIL, the regular Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) attacked one another with airstrikes, heavy shelling, and firefights in streets of the capital Khartoum, and in other cities and regions.

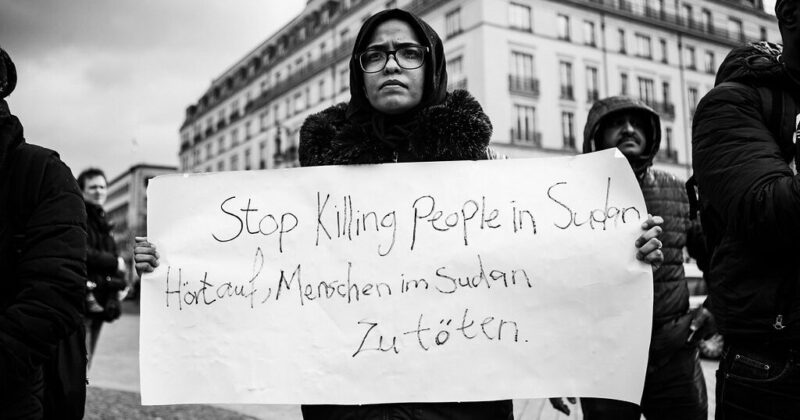

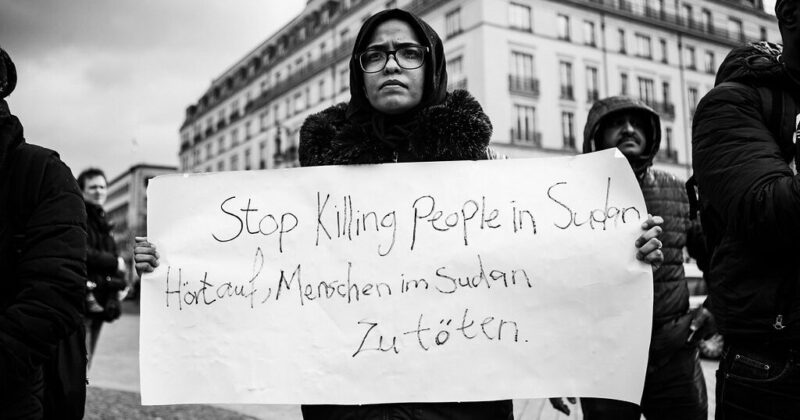

Both sides have shown no regard for civilians in densely populated areas, who have been trapped in their homes, unable to go out for food, water, or medical supplies. Within days hundreds of civilians have been killed and roads are even more dangerous, making escape from the fighting impossible. Elsewhere, including Darfur, thousands of refugees are reported to be crossing the country’s borders.

The fighting reveals the cynicism of the military’s claim to be undertaking a ‘transition to democracy’. In fact, the 2019 democratic revolution was brought to an end by the military coup of 25 October 2021, led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan of the SAF and the RSF’s Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti. Both represent factions which are exploiting Sudan’s major gold reserves, oil and other minerals. Now these thieves have fallen out and are making their people pay the price.

This development has demonstrated once again that, during a mass popular revolution, if the generals’ control over the army is not broken, with rank and file soldiers coming over to the people, a counter-revolution will follow just as night follows day. Only if the generals exhaust themselves with their internecine conflict, the soldiers revolt against the killing, and the masses can take to the streets once again can there be hope of resuming the revolutionary advance.

But this time they must not stop until they have taken power with their own resistance committees, joined by soldiers’ delegates. Only a victorious revolution of workers, soldiers and peasants can bring lasting peace, democratic rights and social development to the people of Sudan and, indeed, inspire its imitation in the surrounding regions.

Civil war

The SAF under al-Burhan is trained by his ally Egypt and has heavier weaponry, including tanks and an air force, which the RSF lacks. But the 100,000 strong RSF commanded by Hemedti is no pushover. Veterans of counter-insurgency and ethnic cleansing in Darfur and other regions, up to forty thousand RSF troops have fought in Yemen on behalf of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

The UAE is Hemedti’s patron and the main outlet for the gold from the mines he controls, making his family one of the richest in Sudan. This wealth has given his forces considerable independence from the SAF and the Sudanese state. The Khartoum elite may look at the RSF as a provincial rabble, but they are a battle-hardened, well trained force equipped with armoured vehicles. Also, Hemedti’s links to the powerful Russian mercenary Wagner Group, who are jointly exploiting the mines in Sudan and in the Central African Republic, can provide more hardware and expertise, including helicopters.

Hemedti, the son of a local chief, a camel trader, began his career fighting over resources and loot in the Janjaweed tribal militias that came to prominence in the war that broke out in Darfur 2003. Notorious for its atrocities, it was organised into the RSF in 2013 by the brutal dictator Omar al-Bashir and brought into the capital and major cities where they now have established bases, with 20,000 RSF soldiers based in Khartoum alone. Al-Bashir’s aim was to protect himself from coups by the military, and growing opposition including in sections of the ruling class.

But al-Burhan and Hemedti together turned on al-Bashir and overthrew him in April 2019 in a preventive coup, to head off a mass popular revolution. Since then, RSF forces have been implicated in some of the worst attacks on the popular democratic movement, including the Khartoum massacre on 3 June 2019, in which over a hundred protestors were killed in an attempt to crush the revolution and maintain military rule.

Hemedti may be a thug and war criminal but he is no fool. His first move, that kicked off the conflict, was to attack air bases, focussing on Merowe where he captured scores of Egyptian troops and military trainers in the process. Despite this initial assault, al-Burhan has retained enough air power to strafe and bomb RSF bases and positions in Khartoum, Omdurman and several other cities, and he has maintained control of some television and radio stations, another key target in the RSF revolt, but the RSF too has channels for its propaganda. Both have ruled out negotiations—it is a fight to the death.

Regional backers

There are reports that the Egyptian air force has aided al-Burhan, attacking RSF depots, while others claim that Hemedti has received weapons from the Libyan army commander Khalifa Hafta. Hemedti has already sought support from armed opposition groups in war-torn South Kordofan and Blue Nile states, and in the East where militias based on the local Beja people have occupied Port Sudan.

Sudan’s Red Sea coast is a strategically important area for outside powers, though permission for a Russian naval base has been in legal limbo since 2019. Meanwhile nearby Djibouti, located by the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, separating the Gulf of Aden from the Red Sea, controls the approaches to the Suez Canal. As a result, the country hosts a Chinese naval base, a French airbase, an Italian base and a Japanese base. And last, but very far from least, is Camp Lemonnier, home to the ‘Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa’ of the US Africa Command, the only permanent US military base in Africa.

If Hemedti successfully digs in, aid from the US, Britain, China and Russia, and their regional allies, could allow the two sides to continue their battle. At present, Hemedti is making appeals to stop the conflict, restart the transition, hold elections, and enfranchise the oppressed minorities of the regions. This may be a sign that the RSF is on the ropes. Some commentators report that the SAF is in control of all five capitals of the Darfur provinces, an area the RSF expected to control. One analyst quoted on Al-Jazeera stated that the RSF had no bases left, just pockets of troops ‘without any guidance or central command.’

No doubt millions of ordinary Sudanese people would welcome any end to the fighting and suffering, but a victory either for al-Burhan or Hemedti, let alone a rapprochement between them, will not bring the democratic rights fought for by Sudan’s workers, youth and poor since 2019 nor any relief from their ever deepening poverty, driven by inflation, debt and IMF-enforced austerity. Al-Burhan has as much blood on his hands as Hemedti, and was equally important to Bashir’s regime and its genocide, as a military intelligence colonel coordinating army and militia attacks in West Darfur from 2003 to 2005.

The democratic fiction

The war between al-Burhan’s SAF and Hemedti’s RSF is not just a falling out of two strongmen but the bitter fruit of the incomplete 2019 revolution. After mass struggles and strikes began to influence rank and file SAF soldiers, an August compromise left al-Burhan and Hemetti as chair and deputy chair overseeing a ‘sovereignty council’, half military and half civilian, publicly committed to a three year ‘transition’ to democracy by 2022.

This strategy, pushed by the liberal and reformist leaders of the Forces for Freedom and Change and their US and UK backers, has proven to be a very bloody dead-end for the working people of Sudan. The rotten compromise, which many workers who struggled in 2019 reluctantly accepted as a necessity to avoid bloodshed, has kept the military and security services intact and allowed repeated killing of protesters by RSF and SAF troops and the police.

In September 2021, the transitional government’s foreign minister Mariam Sadiq Al Mahdi of the Umma Party, foolishly stated that Sudan, with its joint military-civilian transition, had become ‘coup-proof’. Less than a month later al-Burhan overthrew the civilian government with Hemedti’s support, before appointing a new ‘transitional’ council with hand-picked, loyal civilian politicians, even getting the Prime Minister and career UN economist Abdullah Hamdok to return, until mass protests forced him to resign in January 2022.

According to Sara Abdelgalil, a spokesperson for the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA) in 2022, ‘there has been no reform to the judiciary, no reform to the security sector’. The courts have acquitted several Islamist leaders including the NCP’s former head Ibrahim Ghandour, who predictably supported the 2021 coup as a ‘corrective’. Since the coup, al-Burhan has filled key positions with old Bashir supporters, from the foreign secretary, governor of the central bank, and ministers for labour, commerce and cabinet affairs.

Crucially, the director of the general intelligence service and head of the judiciary are both old Bashir-era reappointees, and directly responsible for rehabilitating the old regime’s figures—or repressing democracy activists. The committee to investigate corruption has been neutered and beneath these high-profile appointments, hundreds of NCP-era public officials who had been removed from office for corruption had been reinstated. Sudan academic Willow Berridge pointed to an ‘iftar’ (Ramadan dinner) held by NCP leaders openly in the Kobar district where Bashir is imprisoned, which took place just before the coup.

Hemedti has played every political card to bolster his position, including accusing al-Burhan of bringing back ‘the Islamists’—after all, the old al-Bashir hierarchy has no love for this treacherous Janjaweed. Under pressure from the ‘quad’ of the US, UK, UAE and the Saudis, al-Burhan agreed another plan for a transition on 5 December 2022, a ‘framework agreement’, which pushed transition even further into the future. However, this agreement included provision for an early merger of the RSF into the armed forces, a move which would cost Hemetti his independent power base. Once the 11 April deadline for this to occur passed, a major showdown was inevitable.

Permanent revolution

The trade unions and resistance committees that mobilised the 2019 revolution have been forced to convert themselves into aid bodies during the coup, helping feed and provide medical assistance to people and protect civilians. Where possible, these organisations should fraternise with the soldiers and build political protests demanding food, water, hospitals administered under their own control.

If al-Burhan wins, but a civil war with the RSF forces on the peripheries breaks out, they should revive the mass struggle for full democratic rights and class demands for welfare, jobs and union rights. Such a struggle would be the best conditions for turning the resistance committees into genuine popular councils (soviets) led by the organised working class, with the authority to appeal to the soldiers as the sons of the working people. That requires building the resistance committees into a national congress of factory committees and soviets that can seize power as well as the productive property of the generals, landowners, and capitalists.

Socialists in Sudan need to be clear that restoring the revolution and resisting civil war means a showdown with the military commanders, rejecting the bourgeois politicians of all stripes, but also taking up the right to self-determination of oppressed minorities. The position of the influential Sudanese Communist Party, based as it is on the Stalinist strategy of a revolution, offers a reactionary utopia—‘a professional unified national army based on competence, integrity and national creed away from political party, regional, national, communal and tribal allocations’.

After the failed experiment of cohabitation of civilian and military rule, millions can see that establishing democracy means smashing the entire repressive state, with the corrupt generals at its core. Only a revolutionary constituent assembly, organised by a revolutionary workers’ government, can resolve burning questions of democracy, property and oppression. It could harness Sudan’s mineral wealth, its industry, and the large scale agriculture of the Gezira breadbasket to a democratic plan for the needs of the masses, led by the working class, and eliminate the draining of the country’s wealth by kleptocratic elite and the Western banks. This socialist transition can be made permanent by extending the revolution further into Africa and the Middle East.