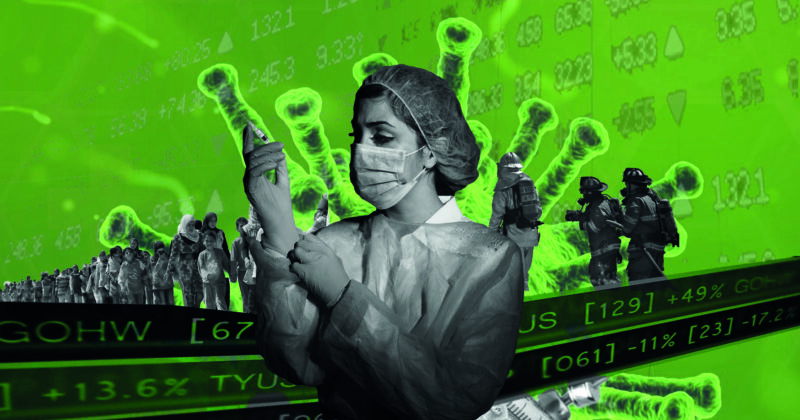

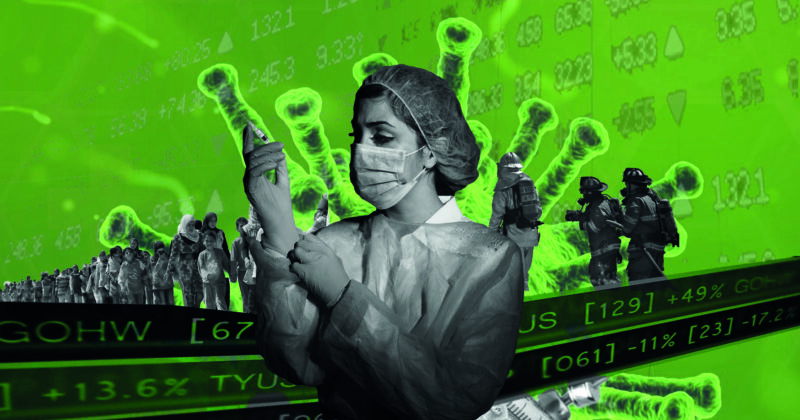

THE INTERNATIONAL CRISIS of the coronavirus pandemic has exposed the stark inadequacies of the capitalist system in a number of ways. Whether it is the lack of funding for the health system, deficiencies in education and childcare, or the fragility of the economy, it has shown how the social system as it is currently structured is unable to cope with such a crisis. It has shown how these inadequacies operate at every level, from the top tiers of economic and governmental system, down to the level of the workplace and classroom.

There has been much talk in the media and by politicians of the “economic cost” of the crisis. By this, they mostly mean the impact on profits of shutting down workplaces in order to limit the rate of infection. Despite the government’s announcement of a “lockdown”, the decision of whether workers should still attend their workplace is, in most cases, still down to the employer and, as a result, many workers continue to be forced into working in unsafe conditions, risking infection. Despite the severity of the crisis, many workers continue to face obstacles to taking time off sick or to isolate.

The everyday experiences of millions of people in their workplaces is proof that capitalism is structured in a manner which will not only fail to tackle this crisis adequately, but will actually deepen and worsen it. Sickness policy is a topical example. The system is in most cases set up so that people are penalised for taking time off if they are ill. From the capitalist’s perspective, time off work due to illness is time when workers are not creating value for them, and so any amount of sick pay is an unwarranted deduction from profits.

Sick Pay

Britain currently has one of the lowest sick pay rates in Europe, higher only than Malta. In fact, in 2018, the European Committee of Social Rights ruled that the United Kingdom’s sick pay policy was failing in its legal obligations to the European Social Charter in regards to workers’ sickness. The current statutory sick pay rate of £94.25 a week, the equivalent of £2.51 per hour, is completely inadequate for meeting workers’ needs. While some workers may have better terms laid out in their contracts, based upon their own rates of pay, many, particularly low paid and unskilled workers, are reliant upon statutory sick pay legislation. Those who earn less than £118 per week are not even entitled to that. The self-employed are also not covered. Of course, as a result of these restrictions, women workers are disproportionately affected, as are older and younger workers. The TUC estimates that of the 1,870,000 workers not entitled to sick pay, 70 per cent are women.

Workers employed on a casual basis, or through an agency, may not be paid at all if they are unfit to work. Zero hours contracts are set up so that there is no guarantee of work. This is used by employers to ensure that they are only paying workers the absolute minimum; as a result, many workers will go through periods where they do not meet the threshold for statutory sick pay, and it is extremely unlikely that such contracts will have any sick pay provision beyond the statutory minimum. Similarly, employment agencies will often be used to bypass contractual obligations, and the agencies will rarely pay more sick pay than the statutory requirement. Again, due to the casual nature of employment, workers will often fall short of the statutory threshold. In a number of industries, such as in construction and transport, there has been an increase in the use of bogus self-employment, with workers setting themselves up as their own limited companies in order to gain employment, often on a casual basis. These workers will not be entitled to statutory sick pay, whatever their earnings.

Companies that employ workers on permanent contracts have systems established which limit the time employees can take off sick (usually over the course of a year), before they trigger disciplinary processes, which could eventually lead to their dismissal. This functions not only to ensure that people do not go off sick unless they are genuinely ill, but to ensure that an employer does not have to continue paying for a worker who, due to illness, is providing less labour time for the employer in exchange for their pay, and is therefore creating less profit for them. Whether the worker is genuinely ill or not is therefore largely irrelevant to the capitalist, whose primary consideration is whether the worker is profitable to them.

Shirkers or Sick Workers?

These are the formal mechanisms in place to ensure that workers are penalised if they are ill. However, there are also a number of informal processes that operate in many workplaces. The first line of defence is often the application of moral pressure, in which a culture of disbelief towards sickness is cultivated, where people who are off ill are treated with suspicion or accused of ducking work.

Routine understaffing means that sickness absence increases the workload of others. This can lead to workers feeling obliged to work or to feel bad if they can’t. All of this contributes to a workforce that informally polices itself, with people working when unwell, either for fear of incurring the displeasure of their colleagues or worrying about increasing their own workload.

Capitalist ideology pervades all the social institutions in our society. We are taught from a young age, by our parents, the education system, religious institutions and others, to value “hard work”, and that poverty is a result of laziness. These values, of course, are those of a society based upon the exploitation of labour, which requires people to believe that there is an inherent goodness and morality in working hard for an employer. This is carried on throughout our lives, in the media and by political parties, who draw lines between “hard working families” and those who are benefitting from a “something for nothing culture”. The tabloid press, especially, conducts hate campaigns demonising the “lazy” unemployed and the “work shy”.

Without exposure to an alternative ideology, workers internalise the values of capitalism, which leads them to believe that there is a moral premium upon working hard and being a “good employee”. Many workers therefore push themselves to work when unwell, and take pride in not calling in sick unless absolutely necessary. Inevitably this leads to some workers contributing to the moral pressure placed upon others to avoid calling in sick, or even participating in a culture of victimisation of those who do so. Managers can strike up a workplace culture victimizing “shirkers”, either through “jokes” and “banter”, or nastier forms of bullying.

Labour and alienation

Of course, the issue is not just that people will naturally be unwell at some point, and unable to attend work. It is also the case that work makes us ill. Many people work in physically demanding or dangerous roles which may lead to their health being adversely affected; but also, the very nature of work under capitalism will contribute to poor mental health. Work roles under capitalism are alienating, in that we are separated from the product of our labour, and work is therefore unfulfilling. We are mostly engaged in boring, repetitive, and stressful tasks for which we receive scant material, much less spiritual, reward. Sickness, often as not, is a direct result of our work under capitalism.

Much of the capitalist approach to illness has its roots in what Karl Marx referred to as the “commodity fetish”. Capitalism reduces human interactions to the buying and selling of commodities. Labour is a commodity, bought and sold on the labour market, but a portion of our working day is unpaid – it is this unpaid portion that makes up the capitalist employer’s profits – what Marx referred to as “surplus value”. Workers who are off sick, therefore, are not being paid for nothing. Overall (over the course of a year for example) the capitalist is still profiting from employing them. Sick pay policies are calculated to minimise time off so that it does not cut into this portion of unpaid labour and profit and does not rise to the point where the overall sickness of the workforce becomes unprofitable.

Through collective action in trade unions, workers have won the limited rights they currently have, such as sick pay. However, these are under constant threat, and the increase in recent decades of precarious work has led to these rights to be virtually non-existent for many workers. The limitations of this system, and the commodification of labour which produces it, have been exposed by this health crisis. An entire system set up to penalise workers for being ill, means that when society as a whole is best served by workers making a rational judgement as to whether they are ill, and staying home for the good of all if they are, there are many workers forced to work when ill, and many more forced to work with infectious workmates as a result. This is far from ideal when society needs to contain the disease.

We can therefore see how a crisis, such as the one we are currently experiencing, can expose the unjust and chaotic nature of the capitalist system for all to see. A system built upon the treatment of people as nothing more than sellers of their labour will lead to their own health being of little consideration when compared to the profit they can or cannot generate for their capitalist employer.

Our entire economic and social system is based upon the dehumanisation of workers. It is because of this that the capitalist class, and its representatives in government, has had a wholly inadequate response to the coronavirus outbreak. The wellbeing of people has been, at best, a secondary concern to that of securing capitalist profits. Only when workers liberate themselves and overturn this unjust and exploitative system, and found one based upon the common need of all, can we put an end to practices where the health, and the lives, of human beings comes after the profits of capitalism.