By Eamon Maguire

The Limerick Soviet took place during the War of Independence. Until very recently this period was regarded as something sacred in Irish history. The narrative of patriotic sentiment driving a unique period of heroism, culminating in national liberation was unchallenged. The Limerick Soviet, with its socialist nature and its betrayal by Sinn Fein, the Catholic hierarchy and the leadership of Irish Labour did not fit into this picture and so was omitted from historical accounts.

The story begins with the death of Bobby Byrne on 6 April 1919. Bobby was an officer in the IRA as well as a trade unionist, a delegate to the Limerick Trades and Labour Council. He was arrested following the discovery of arms in his mother’s house and went on hunger strike for political status. An attempt at forced feeding left him gravely ill and he was removed to hospital, where the IRA botched an attempt to free him. This left a police constable dead and Bobby himself fatally wounded. He died on the same evening.

On 10 April a huge crowd, estimated at 15,000, attended Bobby’s funeral. Interpreting this as a gesture of defiance, the newly appointed British military commander for the area, General Griffin, designated the city and surrounding area as a “special military area” using the almost unlimited powers conferred on him by the Defence of the Realm Act.

Griffin set up checkpoints on the bridges over the Shannon where the citizens had to apply for a pass. This could only be procured by means of a letter from the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). This was a huge imposition. Limerick City straddles the Shannon and for many a daily commute to work or a shopping trip involved crossing one of the two bridges. This also applied to the delivery of supplies for shops and businesses. This amounted to collective punishment. The city reacted with collective indignation and defiance.

The Soviet

The Limerick Trades and Labour Council unanimously decided to call a general strike. The city’s entire workforce walked out. About 14,000 workers went on strike. The Council controlled the supply of water, gas and electricity and created sub-committees to take charge of food, finance, propaganda and vigilance. A publication called the Workers’ Bulletin was produced throughout the strike. With the Russian Revolution hot news, the city wits named the committee the Soviet. During the two weeks of the Soviet no looting took place and no civil crime was recorded.

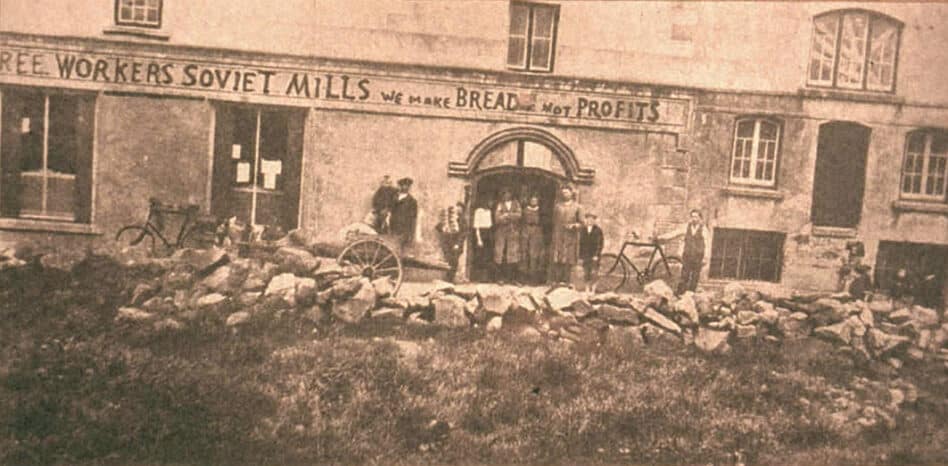

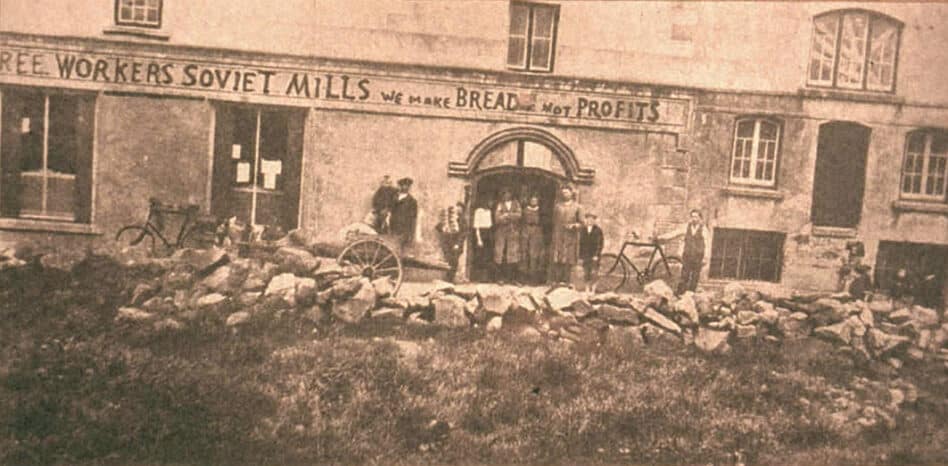

The members of the Soviet were working class men (typically enough for the time they were all men; Mike Finn’s play Bread not Profit premiered in Limerick for the centenary makes this point very cleverly; “what sort of revolution is it when the women are making the tea?”). The Soviet came to an agreement with the city’s bakers, which ensured fresh bread was baked every day. They authorised shops to sell food at fixed prices. The prices were publicised on posters throughout the city. The shops displayed notices announcing they were “trading with permission” of the Soviet.

The Soviet was also capable of daring and imagination. They commandeered the cargo of a ship in the Limerick docks, securing 7,000 tons of grain. That they were willing to risk what might be considered the theft of property worth a considerable sum testifies to their radicalism.

Selected sites outside the military cordon were allocated for food collection and supplies delivered there were smuggled in by supporters. Many ingenious wheezes to outwit the blockades are part of the city’s folklore to this day. The people were actually better fed under the Soviet than they had been during the war.

The populace also harangued and cajoled the soldiers charged with operating the system. In many instances the soldiers (working class lads themselves) relented and let people and supplies through. In the course of the strike an English unit replaced a Scottish one, as the Scots were thought to be too susceptible; 1919 was also the year of the Battle of George Square in Glasgow, Red Clydeside.

As practically the city’s entire workforce was on strike, no one was getting paid. Having received offers of support from many quarters, including trade unions in England, the Soviet had the confidence to create a truly revolutionary solution. They issued their own currency. Local traders accepted the notes. These notes went into circulation, along with a poster listing the shops that would take the Soviet’s money. (The notes have been reproduced in honour of the centenary and are in circulation as a local currency).

With massive solidarity behind them, the leaders of the Limerick Soviet began to believe they could not only overcome the local issue of military tyranny but create a revolutionary paradigm for the whole country. The Sinn Fein/IRA guerrilla war was still a small and scattered affair and its effectiveness open to question.

Many of the strikers were members of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) and the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR). They took the initiative in attempting to broaden the base of the action. On 16 April the Limerick branch, seeking solidarity action from their comrades across Ireland, sent delegates to other branches.

Motorised transport was a negligible quantity in Ireland at the time and anything that had to be transported in bulk or any distance went by rail. People (including soldiers), medical supplies and most postal communication went by rail, as did agricultural produce, the country’s largest single export to Britain.

A national NUR strike would certainly have caused more trouble for the ruling establishment than any number of countryside ambushes. In a way the IRA never could, the NUR had their hands on the system’s windpipe. The trade unionists however were to be betrayed.

Betrayal

With the NUR debating whether to go on strike in support, the Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Council (ILPTUC) intervened to delay the possibility. William O’Brien, leader of the ITGWU and chair of the ILPTUC, instructed the NUR to delay the action, promising an emergency meeting of the national executive to debate the matter.

The Soviet members concluded that this meant that the ILPTUC would call a general strike in the near future. John Cronin, Chairman of the Soviet, told Ruth Russell of the Chicago Times that the ILPTUC national executive would meet in Limerick and, if there were no concessions, proclaim a national strike. (Ms Russell, along with many other journalists, was in the vicinity to cover an air race which was cancelled. This left a large number of disappointed journalists looking for copy and serendipitously secured a huge amount of press coverage for the Soviet.)

Cronin’s trust in O’Brien and the ILPTUC was misplaced. Instead of a general strike, the trade union leadership declared that they would evacuate the strikers to other locations in Ireland, where fellow trade unionists would put them up. It was a spineless and shameful climbdown and a complete betrayal of the strikers and the basic principles of trade unionism. Instead of standing up to oppression they would run away.

O’Brien’s actions are a puzzle. On the face of it a lifelong socialist, friend and associate of both James Connolly and James Larkin, his response to the Soviet and the possibility of a national strike amounted to sabotage.

O’Brien, it appears, had bought into the Sinn Fein agenda that all other considerations were secondary to national self-determination. They completely subordinated every aspect of the class struggle to the nationalist leadership. The first Dail (Parliament), entirely composed of Sinn Fein, would not endorse a national strike in support of Limerick.

Up until this point the city was solidly behind the Soviet. This came to an end, along with the prospect of a general strike. On Thursday 24 April, the Sinn Fein Mayor of Limerick, Phons O’Mara, and Bishop Dennis Hallinan negotiated with General Griffin and issued a letter the following day to put their authority firmly behind ending the strike.

With this intervention the middle classes and the Church, in the persons of the mayor and bishop, reasserted their primacy in decision-making and cut the ground from under the strikers. This set the pattern for the remainder of the War of Independence and the shape of the state to follow.

The Soviet leaders understood that this was the end, and on the 27th announced that only those who were affected by the pass laws would continue the strike. There was a backlash. Some of the posters announcing this were torn down and there was talk of a “new Soviet” but it all petered out.

The military conceded some ground to the unholy partnership of the Sinn Fein mayor and Catholic bishop. For example they accepted letters from employers as opposed to the passes. But the strike’s huge potential as a weapon of resistance was coldly and deliberately stamped out by the supposed leaders of the labour movement in Ireland in collaboration with the nationalists and the Catholic Church.

Conclusion

So ended one of the more interesting “might have beens” of Irish history. The strike was a spontaneous reaction to the collective punishment imposed by the military. But did the leaders have time to prepare the wider labour and trade union movement for the possibility of a nation-wide general strike? Inspirational though the actions of the Limerick workers were (and still are), there was a distinct lack of preparation. O’Brien and the ILPTUC might say they didn’t have time to prepare themselves for a general strike but there is a counter-argument that revolutionaries should be prepared to seize such moments of popular anger, as opposed to nurturing long term plans.

Another drawback of the time was the limitations of nationalism. It came to be seen as the highest political good, to which all other aspirations had to be subordinated.

The patriotic movement had hundreds of years to build its cultural arsenal of songs, novels, poems, interpretations of historical events. This vast cultural construct is only now beginning to be questioned and dismantled. Only in the very recent past has any kind of analysis of the role of the working class in Irish history begun to make headway against the accepted nationalist version.

The nationalists eventually realised their ambition, albeit in a very limited form. The limitations of the eventual settlement sparked a vicious civil war between the former comrades of the armed nationalist movement. The opposing sides eventually coalesced into two political parties (Fine Gael and Fianna Fail) that dominated Southern Irish politics for the majority of the state’s existence.

The material conditions of life under the Free State and its successor, the Republic, were not notably altered. Poverty remained endemic and emigration continued to drain youth and energy from the country, as it does to this day. The primacy of the Catholic Church was enshrined in the workings of the new state in theory and practice.

This had many baleful effects. The Church’s obsession with Catholic purity led to a level of censorship and suppression that left the country a cultural and intellectual desert for many decades. Politics was equally constrained. In the 1970s the then leader of the Irish Labour Party, Brendan Corish, felt obliged to announce that he was “a Catholic first and a socialist second”.

All of these are relatively minor in comparison to the Church’s dominance of social institutions, colluded in by the state. The “reform schools” (for young offenders), orphanages, the now infamous Magdalen laundries were the Church’s exclusive zone of control for more than 70 years.

Given the revelations that have emerged detailing the vicious sexual, psychological and physical abuse that raged unchecked in these places, the misery produced is incalculable. We will never know how many lives were wrecked under this ghastly system. Such was “national self-determination” for the unfortunate victims of this state of affairs.

What the Soviet shows us is that another revolution was possible. Instead of a narrow national state dominated by the Catholic Church, we could have had a worker-led, socially conscious political entity. Above all, for a brief period, it appeared possible that working class people could defeat an empire. We could do with some of that belief today.