By Dave Stockton

THIS YEAR’S celebrations of the anniversary of the foundation of the State of Israel were bigger than ever. They were held on 18 April, corresponding to a date in the Hebrew calendar that in the Gregorian calendar corresponds to 15 May.

And this latter date is when Palestinians commemorate the 1948 Nakba (“Catastrophe”). This is their name for the events whereby between 750,000 and 900,000 Palestinians were driven from their ancestral lands, villages and cities to create a state in which relatively recent Jewish settlers were a majority. Before these events, Arabs had formed two thirds of Palestine’s population and owned 90 per cent of its land.

Israel’s official story of how and why this happened is that the surrounding Arab states broadcast radio messages urging the Palestinian Arabs to flee. This, supposedly, was to allow the armies of four Arab states to invade Palestine and “drive the Jews into the sea”. David Ben Gurion, the “founding father” of the Israeli state, in effect claimed that the Palestinian Arabs fled to enable the Arab armies to carry out a second Holocaust.

Over decades however, not only Palestinian historians but even a handful of courageous Israeli historians have exposed this account as a pack of lies. Zionist paramilitary forces, many armed and trained by the British in the 1930s and 1940s, were by far the strongest of all of the armies on the ground.

By early 1948, the mainstream Labor Zionist movement’s militia, the Haganah, stood at around 50,000, rising by summer to 80,000. It included a small air force, a navy and units of tanks, armoured cars and heavy artillery. Against this, the Palestinians had some 7,000 poorly-equipped irregulars, most of them locals alongside some volunteers recruited from Syria and Iraq. The Haganah could also rely on the support of the more right-wing Zionist militias, like the Italian fascist-inspired Irgun and Lehi (the latter also known as “the Stern Gang”).

The surrounding Arab states – Transjordan, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Egypt – all had only just emerged from British or French colonial rule or domination; and their governments were still dominated by British and French interests. Their armies, good for little more than palace coups and for shooting strikers and demonstrators had been created for the purpose of internal repression, rather than for serious wars with other states.

And of these five countries, Lebanon’s main role in the 1947-49 war in Palestine was to round up and disarm Palestinian refugees and fighters on its territory, rather than to assist them. Only Jordan had a well-trained professional army, the Arab Legion; and it was still commanded by a British general, Sir John Bagot Glubb (“Glubb Pasha”).

Moreover, Jordan’s King Abdullah was secretly negotiating with Ben Gurion (through other Labor Zionist leaders like Golda Meir) for a Jordanian occupation of the West Bank, and for its annexation to his resource-poor kingdom. Both sides wanted to prevent the emergence of a separate state for the Palestinian Arabs under the leadership of the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husseini; or even worse from their standpoints, under the leadership of the Palestinian guerrilla leaders who had fought the British and the Zionists during the Arab Revolt of 1936-39.

Adhering closely to the “red lines” of King Abdullah’s understanding with Ben Gurion – which the British clearly had prior knowledge of – Glubb saw to it that the Arab Legion never at any point in the war occupied any of the territory that had been set aside for a “Jewish state” by the United Nations (UN). The Arab Legion even allowed Tiberias and Safed in the north of the country to fall to the Haganah in April and May 1948, to prevent Husseini from being able to establish a provisional Palestinian government there.

Most of the fighting between the Haganah and the Arab Legion took place because the Zionists tried to occupy areas well beyond this pre-agreed division of the spoils.

Britain plays off Jews and Arabs against each other

The British had previously toyed with the idea of dividing Palestine in the Peel Commission’s proposals in July 1937, as a way of bringing about an end to the Arab Revolt. But the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939 forced them to shelve the Peel Plan to placate Palestinian Arab opinion, much to the annoyance of Jewish colonists who had supported British colonial rule against the rebellious Arabs.

Many of these Jewish colonists had been recruited into the British war effort in Lebanon and Syria, through the British-sponsored Zionist paramilitary organisation Palmach. This became the main legal cover for the underground Haganah until the British stopped funding it in 1942. However, a small minority within the Zionist movement conducted a terrorist campaign against both British and Arab targets in protest at the British “White Paper” that followed the shelving of the Peel Plan, even during the Second World War.

Represented by Lehi’s leader Avraham Stern, this extremist minority even approached the Nazis with a request for German support for the creation of a pro-German fascist state under their leadership, to which Adolf Hitler would then be able to deport German-occupied Europe’s Jewish populations en masse. The Nazis however regarded this proposal as a distraction from the genocidal “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” that they were already undertaking in Europe; and Stern himself was captured and killed in a shootout with British police in February 1942.

However, after the end of the Second World War in May 1945, Lehi were joined by the more “mainstream” right-wing Irgun from which Lehi had originally split in August 1940, in resuming their armed campaign to coerce Britain into accepting a Jewish state in the whole of Palestine. The most famous by far of the attacks conducted by these two groups was the King David Hotel bombing in Jerusalem in July 1946, which killed 91 people including 41 Arabs, 28 British government employees and 17 Jews.

This armed campaign enjoyed the occasional if indirect support of the official Labor Zionist leadership around Ben Gurion, and threw British policy in Palestine into crisis. Unwilling to be seen to “take sides”, and in order not to disturb its relations both with the Zionist movement in Palestine and with its own client Arab regimes, British imperialism cynically handed over the “Palestine problem” to the newly-formed UN, then still dominated by European powers with large colonial empires of their own.

Britain acts as midwife to massacre

The UN then arrived at a detailed plan for the partition of Palestine into Arab and Jewish states, although with only voluntary “transfers” and “exchanges” of populations stipulated in it. Arab governments and Palestinian Arab leaders overwhelmingly rejected the plan, awarding as it did roughly half of Palestine to the Jewish one-third of its population, in a proposed “Jewish state” in which Arabs even then would still form a slim majority. Assuming, of course, that they remained there.

On the other hand, Ben Gurion and the mainstream Labor Zionist movement accepted the UN Partition Plan, seeing it as a springboard for future Zionist aspirations in Palestine as a whole; while the “Revisionist Zionist” Irgun and Lehi both rejected it. For the right-wing Revisionists, this plan fell far short of their original demands for a Jewish state on both sides of the River Jordan.

Both wings of the Zionist movement, however, had the full intention of turning Jews into an overwhelming majority of the population there by “redeeming” the land from its indigenous population; that is, by expelling Arabs and importing Jewish immigrants and refugees from Europe, the Arab world and elsewhere.

In fact, the UN Partition Plan gave the Zionist movement far more land than was then owned or controlled by Palestine’s Jewish settler minority. And to achieve the “Jewish majority” that would give a Jewish state in Palestine any political or demographic viability, it was necessary to put into operation a number of plans that had been drawn up years or decades beforehand, to drive the Arabs out.

The most comprehensive of these was known as Plan Dalet (or “Plan D”), which informed most of the Hanagah’s military actions in 1947-49. This envisaged the forced transfer from their lands of hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs in the Arab-majority rural Galilee region and in the Negev Desert; as well as the ethnic cleansing of Palestine’s major towns and cities, especially the ports like Haifa, Jaffa and Acre.

Britain’s response to the Partition Plan in November 1947 was to “wash its hands” like Pontius Pilate. Britain simply announced that it would terminate its former League of Nations Mandate over Palestine on 14 May 1948. The Zionist Jewish Agency for Palestine, a quasi-state body established by the British and led by Ben Gurion, then unilaterally declared the independence of the new State of Israel on the same day as Britain’s formal withdrawal.

In the intervening six months, however, Britain was still officially responsible for maintaining “law and order” in Palestine. But British forces in effect had withdrawn to their camps, and British-officered police stations did absolutely nothing to protect those (overwhelmingly Arabs, but also some Jews) from being massacred or displaced.

This perfidy was entirely of a piece with Britain’s actions during the Partition of India only a few months prior, when Britain stood aside and did nothing to prevent the terrible communalist slaughters and expulsions of millions, previously having spent decades setting Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs against each other. Both exits from Empire remain terrible stains on the record of Clement Attlee’s much-lionised Labour government of 1945-51.

In the actual event, the new Israeli state’s well-armed and well-trained militias seized 78 per cent of the former British Mandate territory, far beyond the 56 per cent awarded to them by the UN. In the process, some 530 Arab villages were destroyed or emptied of their Arab residents, as well as the Arab quarters of all the major urban areas, even including the western parts of Jerusalem. Jaffa was attacked on 25 April 1948 by the “official” Haganah, acting alongside the even more murderous Irgun. Its Arab population of 100,000 was reduced to 5,000 in a few days.

These atrocities were not simply carried out in the hot blood of combat, but were designed coldly and deliberately to spread panic, and thus to induce the indigenous Arab population to flee. According to the Israeli military historian Arieh Itzchaki, there were ten major massacres and about 100 smaller massacres perpetrated by various Zionist militias during the Partition.

Caesarea (“Qesarya” in Arabic) was the first village to be expelled in its entirety, on 15 February 1948. Another four villages were “cleansed” on the same day, all recorded by watching British troops stationed in nearby police stations. Another village attacked that same night was Sa’sa’ near the Lebanese border, where the officer in charge Moshe Kelman later recalled: “We left behind 35 demolished houses (a third of the village) and 60–80 dead bodies (quite a few of them were children)”.

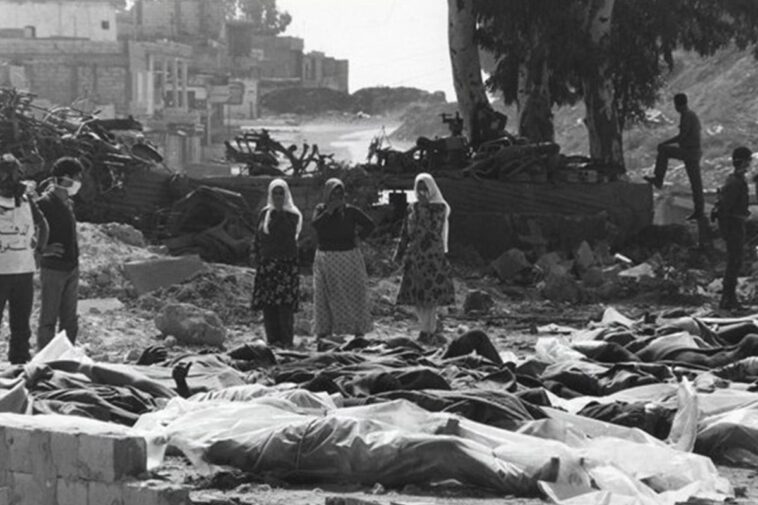

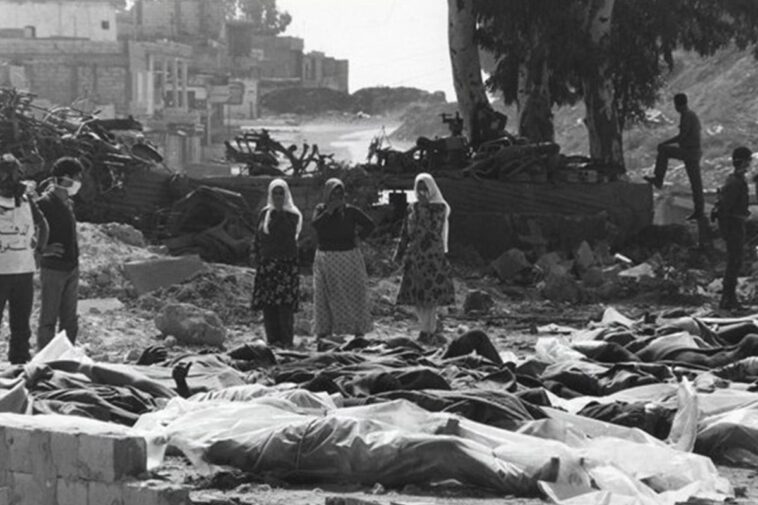

Deir Yassin

The most infamous Zionist massacre of all however took place at Deir Yassin village near Jerusalem on 9 April 1948. It was carried out by the Irgun and Lehi militias, whose national commanders respectively were Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir. Both later became politicians for current Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s right-wing Likud party, each serving as prime minister themselves in 1977-83 and in 1986-92 respectively.

The responsibility for this massacre has generally been placed on these two militias alone. This in part is because Ben Gurion admitted to and “apologised” for the massacre at the time, in a bid to shift international blame onto his right-wing rivals. But Israeli “New Historians” like Ilan Pappe have shown that Haganah commanders approved of their plans, and even sent the Palmach to Deir Yassin to help them finish it off.

This massacre however had an immediate effect on Arab civilian morale. Its scale (exaggerated from the actual figure of 107 dead to some 254) was used to terrify other villages and city districts. Trucks carrying loudspeakers broadcast the news and urged Arabs elsewhere to flee to escape a similar fate.

This village of only 600 people lay just a few miles to the west of Jerusalem. It villagers had signed a non-aggression pact with neighbouring Jewish settlements and even with Lehi commanders. It had at most around 30-odd armed villagers for its defence.

Some 132 Irgun and 60 LEHI commandos stormed into it as dawn was breaking. Ilan Pappe’s 2006 book The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine sums up what happened:

“As they burst into the village, the Jewish soldiers sprayed the houses with machine-gun fire, killing many of the inhabitants. The remaining villagers were then gathered in one place and murdered in cold blood, their bodies abused while a number of the women were raped and then killed”.

Born in Deir Yassin, a recent documentary film by Israeli director Neta Shoshani collected a series of eyewitness accounts, including from some Israelis involved in the events. One was Yehoshua Zettler, the Jerusalem commander of Lehi. In a candid but unapologetic interview, he described the way in which Deir Yassin’s inhabitants were killed:

“I won’t tell you that we were there with kid gloves on. House after house […] we’re putting in explosives and they are running away. An explosion and move on, an explosion and move on and within a few hours, half the village isn’t there any more.”

Another witness was Professor Mordechai Gichon, who was a Haganah intelligence officer sent to Deir Yassin after the massacre ended:

“To me it looked a bit like a pogrom. If you’re occupying an army position – it’s not a pogrom, even if a hundred people are killed. But if you are coming into a civilian locale and dead people are scattered around in it – then it looks like a pogrom. When the Cossacks burst into Jewish neighbourhoods, then that should have looked something like this.”

Despite Ben Gurion’s and the Labour Zionists’ attempts to present this and other massacres as the exceptional results of the actions of a few extremists, these “extremists” were not punished in any way. Indeed they eventually succeeded the Labour Zionists in power in Israel in the 1970s, and continued the same murderous methods in southern Lebanon the 1980s. And these “respectable” extremists never apologised once for their actions in 1948. Quite the opposite.

Menachem Begin, who was later awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1978, wrote in in his memoir The Revolt: Inside Story of the Irgun in 1951 as follows:

“The massacre was not only justified but there would not have been a state of Israel without the victory at Deir Yassin.”

He went on:

“The legend of Deir Yassin helped us in particular in the saving of Tiberias and the conquest of Haifa. […] All the Jewish forces proceeded to advance through Haifa like a knife through butter. The Arabs began fleeing in panic, shouting ‘Deir Yassin’!”

Today, Israeli Defence Force snipers are killing dozens of unarmed Palestinian demonstrators and wounding hundreds on the border fence with the Gaza Strip. These demonstrators are trying to use their commemorations of the 70th anniversary of the Nakba to break through the Israeli and Western media’s blackout of their still-desperate situation.

And the appallingly racist and pro-Israel US President Donald Trump is threatening to open the US embassy in Jerusalem in person on or around 15 May.

It is therefore vital that the global movement of solidarity with Palestine make clear that a state born out the expropriation of a entire people – a racist state created on the basis of a hundred Deir Yassins – has no right to continue to exist on this basis.