Support workers' struggle in Brittany

By Marc Lassalle

This autumn, “Socialist” President François Hollande and Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault have been facing an upturn in the class struggle. Until recently, they have been successful – thanks to the trade unions, and the student union UNEF, in defusing, or at least applying the brakes to, any workers’ and social struggles. This is a government that won office by promising to expand the economy and provide an alternative to the policies of right wing President Nicolas Sarkozy. Yet, almost from day one, Hollande continued to manage the system with the same policies as his predecessor; state handouts for the bosses and austerity for the workers.

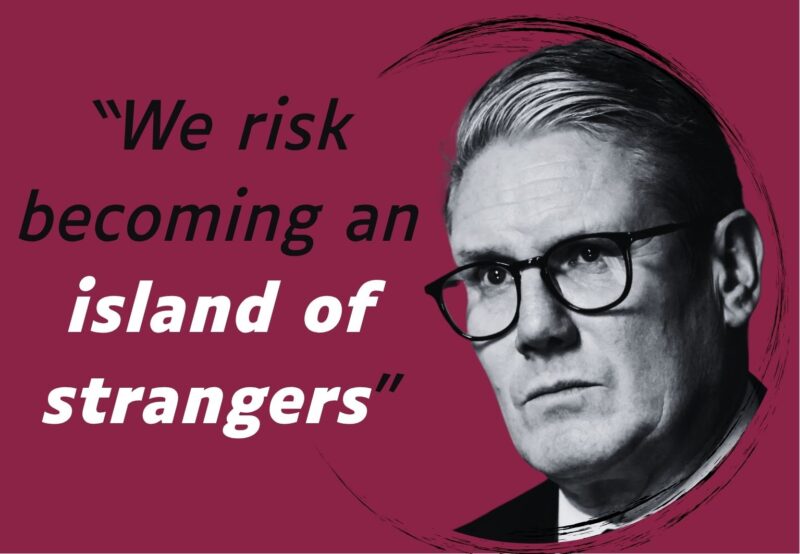

Despite the shameless junking of his election promises, Hollande’s increases in VAT and his attacks on workers’ legal rights have been passed without any serious opposition from the official labour movement. To this must be added racist pandering to the voters of Marine Le Pen’s Front National, like the call of Interior Minister Manuel Valls for most of France’s 20,000 Roma to go ”back home” and “be integrated over there”… or face forcible deportation.

In September, however, some 370,000 protesters took part in 200 demonstrations across France against the government’s proposals for pension “reforms.” An even more militant response came at the end of October when the Socialist government lit the fuse of revolt, ordering the deportation of two lycée students; 15-year old Roma Léonarda Dibrani and the 19-year-old Armenian Katchik Katchatryan. As so often over the last ten years, it was France’s high school students who took decisive action. Across France, they walked out and demonstrated in large numbers against this cruel victimisation.

Now, even bourgeois commentators have started to warn of the danger of a new social explosion. In a recent internal memorandum to the government, prefects described “a society racked by tension, exasperation and anger. This mix of discontent and resignation expresses itself in an eruptive way, through a succession of rapid, almost spontaneous, fits of anger and not through structured social movements”.

A week later, in Brittany, angry workers threatened with lay-offs and unemployment took to the streets mobilising other social layers, like farmers and small business people. The crisis has hit Brittany particularly savagely. It is historically an underdeveloped region whose economy is largely dependent on farming and the food processing industries. A series of closures of small industrial enterprises has severely hit the region. They are often the only major employer in a town. This was the case for Doux (poultry), for Gad (a pork slaughterhouse) and for Marine Harvest (salmon).

At a solidarity meeting against these closures, the workers decided to call for a demonstration in Quimper on November 2. This call also drew in other social forces affected by the closures; small farmers , fishermen, shopkeepers and the bosses of small firms. The demo was a great success with 30,000 people calling “for jobs, to live and work in Brittany”.

Given that this was only a regional event and that no national political force called for it, it was hardly surprising that the demo had a pronounced regionalist component with many Breton black and white “national” flags and many cultural nationalist movements and parties involved. The movement in Brittany, whose members are called “bonnets rouges” (red caps) because they adopted the symbol of a 1675 tax revolt against the centralising monarchy of Louis XIV, shows both the potential and danger of the current situation.

What lies behind this outpouring of resentment is the reality of precarité and unemployment, made worse by the bad economic situation of the country. In the last year alone, 1,000 collective sackings (“plans sociaux”) have destroyed hundreds of thousands of jobs. Even large companies like Air France, Alcatel-Lucent, Sanofi and PSA have slashed jobs. While the President had promised that unemployment should start to decline by the end of the year, it has never been so high and the prospects for next year are just as bad.

Indeed, two parallel processes are taking place. On the one hand, the right wing political forces have definitely tried to take the leadership of the movement and steer it into a demonstration against the government and against taxation.

In the main media, the demonstration was described as being simply against taxation and in particular against the “eco-tax” – a measure decided by Sarkozy but now implemented by Hollande. This levies a tax on all trucks based on the length of their journeys. While the government pretends it is ecologically motivated, these funds will in the end be used for road construction or repair. Moreover, in a typical example of a public-private partnership, the joint venture collecting it (the state rail company SNCF and other big private corporations) will keep a huge portion (20 per cent) as their profits. In many small towns, burning the equipment used for the ecotax was the main action underway.

On the other hand, the much bigger problem is that the big battalions of the workers’ movement abandoned the Quimper workers to the right-wing forces. The CGT organised a separate, much smaller, demo in Carhaix, 70 km from Quimper, on the same day: and even the more radical federation, SUD, went along with this. The Parti de Gauche (PdG) leader, Jean-Luc Mélenchon denounced the Quimper demo as “slaves marching behind their masters”.

Fortunately, the spokesperson and former presidential candidate of the Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste (NPA), Philippe Poutou, did join the Quimper demonstration. This decision was fully justified, for all the mixed social character of the marchers, and the speakers, at the rally. Most of the marchers were workers or from other classes exploited and oppressed by the system. Standing aside from their struggle would simply leave the way wide open to right wing forces, such as the FN, to dominate the movement. Mélenchon’s attack on the march was typical of his empty demagogy.

Unsurprisingly, the Communist Party daily l’Humanité joined in the attacks on the NPA for marching in Quimper “together with FN and the bosses” – a bit rich coming from the historic practitioners of the Popular Front. In fact, this supposed class purity is not what it seems. In reality, the PCF is just sucking up to the SP in the hope of gaining or retaining seats in the local elections due in March. So much so that a major row has developed between them and Mélenchon and the PdG.

The danger of the movement in Brittany, and perhaps others that will arise in areas hard hit by unemployment, is that, whilst the working class provides the main forces for these protests, it is not armed with an independent political perspective but is steered away from this by social forces hostile to its class interests and infected with racist and chauvinist slogans.

This is what will tend to happen in periods of apparent social peace, when the union leaders hold back on struggles, The real temperature of the effects of the crisis can only be registered by the thermometer of a vote for FN. In a series of local and partial elections, the FN score has grown, reaching more than 40 per cent on the latest occasion, in Brignoles (Var, southern France). For many, voting FN seems like a way to express disgust with the whole system, even if they do not understand or fully agree with the FN programme.

More generally, petty bourgeois and reactionary forces are growing across Europe. In most cases they offer what seem like “easy” answers to the crisis, often linking high unemployment with immigration. The Beppe Grillo movement in Italy or the anti-EU UKIP in Britain are examples of this. The basic reason is the shameful role of the main Labour, Socialist or Social Democratic parties of the continent. By supporting bailouts for the bosses and cuts for the workers and the lower middle classes, they present the right with a golden opportunity. Added to this, the trades unions allied most closely with these parties restrict the resistance to the cuts to single days of action “with no tomorrow” as French workers say.

This tendency can seen in the current position of the leaders of all France’s main union federations. The CFDT, FO and CGT have failed to give any support to the rank and file struggles and instead cover up for the Hollande government. They have all continued to negotiate with it and appear totally cut off from their rank and file. These leaders condemn what they call the “populism” and “corporatism” of movements like that in Brittany. They call instead for a “truly progressive tax on income”. However, they failed to organise even the smallest demo against the increase in VAT, a harshly regressive tax particularly hitting the working class and the unemployed.

The NPA took a courageous and correct position on the Brittany mobilisation. They called for an end to the sackings, and for the nationalisation of all the factories announcing them. The NPA correctly call for fighting unity between the various fronts of social revolt. However, they do not clarify what their main political slogan of the day – an “anti-austerity government” means. Clearly, it is addressed to the Front de Gauche for joint political activity but does this mean a struggle for a workers’ government coming out of a mass struggle and its organs (coordinations) or does it just mean a coalition reformist government, with or without the NPA’s participation? Playing with ambiguous governmental slogans does not help.

Today, the activities of NPA members are more directed towards the preparation of the next round of local elections in March. Of course, the NPA is right to stand candidates and to use the campaign to popularise a strategy for resistance. But it should also be throwing the majority of its forces into a national campaign, based on a plan of action, uniting workers, teachers, youth and other sectors hit by the crisis to halt the austerity plans of the government. The potential for a major social explosion certainly exists.

However, if its development is left to pure spontaneity, the results could either be the failure to organise a collective resistance nation-wide, with only isolated upsurges such as we are seeing or, even worse, reactionary social forces will seize the initiative and mislead the non-unionised majority of the working class, adopting reactionary demands, with severe consequences.