By Tim Nailsea

There are signs of growing tensions between the Communist Party of Britain (CPB) and its youth wing, the Young Communist League (YCL). Lawrence Parker’s blog recently reported an internal memorandum by the Communist Party leadership, that instructed its members against public “adulation of Stalin and support for the substantial abuses of state power which occurred under his leadership”. This instruction was clearly aimed at members of the YCL, among whom such behaviour, online and on demonstrations, has become increasingly common. The memorandum comes only a few months after the Communist Party of Ireland’s youth wing, the Communist Youth Movement, split from its mother organisation.

The Young Communist League

The YCL is organisationally independent of the CPB, but they share many members, and both adhere to the Communist Party’s Britain’s Road to Socialism programme. Tensions between the YCL and the CPB are of interest to the British left, as the YCL has recently experienced a surge in membership and visibility. Left and trade union demonstrations have come increasingly to include visually striking and loud YCL blocs, where young communists march in a group with matching red masks and flags, often chanting about Stalin, Che Guevara, and Ho Chi Minh (even if those demonstrations are against climate change or in support of striking bin workers).

The YCL’s approach is marked by outward celebration of figures such as Stalin and use of Soviet symbology. They are also more aggressive in their assertion of Stalinist politics towards other tendencies on the left and seem sceptical of the more pedestrian approach of the CPB and the established left.

It is quite common for a youth wing of a left organisation to be more assertive, bordering on sectarian, and more susceptible to ultra-leftism. Youth groups tend to be less rooted in working-class organisations which require patient activity and working alongside others. Young people are also more likely to be attracted to radical language and symbolism.

There is also an understandable reaction amongst the youth to the conservatism of much of the established left. For many years, much of the Stalinist and ostensibly Trotskyist left has been focussed upon building and maintaining alliances with trade union bureaucrats, Labour politicians and liberal public figures; a model largely based on the Popular Front method historically pursued by the Communist parties. The dominance of left Labourism in recent years, with the emergence of Corbynism and its hyper-focus on electoralism and repeated capitulation to the Labour right, was also likely to produce a reaction, with more radical elements of the movement looking for an expression.

However, the form that this reaction has taken in the YCL is in many ways a retrograde step. The open celebration of Stalinist theory and the attempts to rehabilitate Stalin himself are not a step in a more radical, let alone revolutionary, direction. The entrenchment of a sectarian approach to political activity, using provocative public statements and activity to pit members against the rest of the movement, is not just juvenile political practice, but will doom the YCL’s many well-meaning young members to isolation and eventual demoralisation.

This issue is ultimately the result of fundamental weaknesses in Stalinist politics, of which the sectarianism of the YCL and the popular frontism of the CPB are but different articulations.

The Birth of Stalinism

Stalinism as an ideology and political practice emerged from the degeneration of the Soviet workers’ state after the 1917 Russian Revolution. In brief, after the Tsar was overthrown in February 1917 by a revolution of the working-class and the peasantry, Russia entered an intense revolutionary period, which culminated in October 1917 with the seizure of power by workers’ councils (Soviets) led by the Bolshevik Party and the establishment of the world’s first workers’ state. Almost immediately after this, Russia was plunged into a brutal civil war, as reactionary forces and invasions by capitalist states – including Britain, France and the USA – attempted to overthrow the workers’ state and re-establish Tsarism and capitalism.

The Bolshevik government achieved a great deal despite the revolution being under siege. The large estates of the aristocracy were broken up and the land redistributed to the peasants, all major industries were nationalised under workers’ control. The workers’ state established a monopoly over foreign trade, and a planned economy based upon the needs of the working classes as a whole.

However, the effects of the civil war and the revolution’s isolation led to a process of bureaucratic degeneration. The revolution’s leaders, the most notable of which were V.I. Lenin and Leon Trotsky, had seen the Russian Revolution as the first stage of a world working-class revolution, and did not believe that socialism could be established in semi-feudal Russia alone. Revolutionary movements in more advanced capitalist countries, such as in Germany in 1918-23, failed, and Russia was increasingly isolated. In the process of fighting the civil war, power was increasingly centralised in the hands of the party’s growing bureaucracy.

As many workers were killed in the civil war or returned to the land rather than face starvation in the cities, the basis of workers’ power and democracy was undermined. The Soviets and factory committees became shadows of their former selves, increasingly dominated by party officials. The alliance between the working-class and peasantry was strained to breaking point by the need to feed the cities and the Red Army, leading to grain requisitions. This period of “War Communism”, with power centralised in the party and the use of violent repression, culminated in the 1921 Kronstadt Mutiny, where sailors in that naval base rebelled against the Bolshevik government and were violently suppressed.

After Lenin died in 1924, the Communist Party leadership became divided as to the next steps for the Russian Revolution. Before his death, Lenin had become increasingly concerned at the growing power of the bureaucracy and suggested a bloc against bureaucratisation with Trotsky. He also suggested in his last testament that the General Secretary of the Party, Joseph Stalin, be removed from his position.

In the manoeuvres that followed Lenin’s death, Trotsky and his Left Opposition increasingly fought against the growing power of the Soviet bureaucracy, of which Joseph Stalin had become the preeminent leader. Stalin first formed an alliance with the conservative “old” Bolsheviks, Zinoviev and Kamenev against Trotsky, then turned upon them too, allying himself with the right of the party led by Bukharin.

The Left Opposition around Trotsky and many of the most distinguished Bolshevik leaders of the pre-1917 and Civil War periods, fought for a programme of industrialisation, democratisation of the party, trade unions and soviets and for a return to the revolutionary policy of the first four congresses of the Communist International (1919-1922) .

Throughout this time, increasingly repressive and violent methods were used against oppositionists, as methods originally used against counter-revolutionaries were turned inwards on party members. In 1929 Trotsky was exiled to Turkey.

Stalin emerged as the unchallenged leader of party and state, exiling, imprisoning and finally killing former allies such as Zinoviev and Bukharin. The one-party monopoly of power over the state was established, with ultimate power invested in Stalin himself. The bureaucracy had become a privileged caste above the working class. While revolutionary measures such as nationalisation of industry, collectivisation of agriculture, and economic planning remained, they became the basis of unbridled power for the bureaucracy, not instruments of working-class democracy. State power was firmly in the hands of the bureaucracy.

The bureaucracy under Stalin embarked on a process of state-building and consolidation of power and broke with the internationalism that was a fundamental principle of the Bolsheviks. Stalin and Bukharin developed the theory of “socialism in one country”, arguing that Russia could build a socialist society separate from the rest of the world, and therefore international revolution was unnecessary. Communist movements abroad became subordinated to the need to defend the interests of the Soviet state.

The Degeneration of the Comintern

After taking power in 1917-18, the Bolsheviks established the Communist International, or Comintern, which supported the revolutionary wings of the international socialist movement to establish national communist parties on the Bolshevik model. As the faction fights of Russia spread internationally, the bureaucratic degeneration of the Russian Communist Party spread to the other national parties, with supporters of Trotsky, Zinoviev and Bukharin harassed and expelled.

With the new theory of “socialism in one country”, the Stalinist bureaucracy no longer saw the survival of Russian socialism as contingent on the spread of revolution abroad, and feared that a new wave of workers’ revolutions could lead to their own overthrow. The activity of the national Communist parties became increasingly subjected to the needs of the Soviet bureaucracy, which aimed to shore up its own position in Russia.

After 1928, when Stalin launched his attack against the Right Opposition around Nikolai Bukharin and forced collectivisation of the land was carried out to speed up industrialisation, the Comintern entered an ultra-left “Third Period”. Social democrats were denounced as “social fascists” and alliances with reformist organisations completely rejected. New “red” trade unions were set up, isolating the Communists from other workers. This ultra-sectarianism was largely a reflection of the Soviet bureaucracy’s lurch leftwards in the process of collectivisation and industrialisation, but the radical rhetoric was also a mask for an increasingly conservative strategy of isolating and consolidating the parties. The ultra-left lunacy of the Third Period culminated in the victory of fascism in Germany and the destruction of the largest and most politically advanced workers’ movement in the world.

After this, Stalinist policy took another lurch rightwards. Fearing the threat of Nazi Germany, the Stalinists put a premium on international alliances with bourgeois states such as Britain and France. The Communist parties were once again instructed to prioritise alliances with the “progressive” bourgeoisie and social democratic leaders. This led to the pursuit of “Popular Front” alliances, which reached its highpoint with support for the Popular Front government in France – an alliance with the social democratic Socialist Party and bourgeois Radicals, which primarily pursued preservation of capitalism against the rising working-class movement.

The same strategy was pursued in Spain, to catastrophic effect. When Franco attempted to overthrow the Popular Front government in 1936, he was only prevented from doing so by a workers’ uprising, and Spain was propelled into a civil war. The Stalinists collaborated with the right-wing social democrats and what remained of the anti-fascist bourgeoisie to disarm and put down the revolutionary workers’ movement, spearheading the violent repression required to do so. The gutting of the revolution from within led to the defeat of the Republican forces and the establishment of Franco’s fascist regime.

It was the turn towards Popular Frontism that solidified the role of the Communist parties as reformist and counter-revolutionary organisations. Despite often sincerely held revolutionary beliefs of rank-and-file militants, many of whom were attracted to the Stalinist parties by their association with the Russian Revolution, the Communist leaderships saw the path to power as alliances with progressive bourgeois and social democrats, the preservation of private property, and incremental reforms through a socialist government. In the capitalist West, Stalinist parties became firmly committed to parliamentary reformism.

Stalinism’s uniquely counter-revolutionary role was also firmly established in this period. As a ruling caste, the Stalinst bureaucracy in the USSR feared workers’ revolution would take away its control of the state. It therefore pushed the Stalinist parties towards opposing outbreaks of revolutionary militancy, on the grounds that it would isolate the movement from the progressive bourgeoisie and social democratic leaders that were necessary for the peaceful transition to socialism. Stalinism is therefore distinguished by peaceful treatment of capitalist leaders and violence towards revolutionary militants, coalitions with liberals and reformists and almost pathological sectarianism towards the revolutionary left.

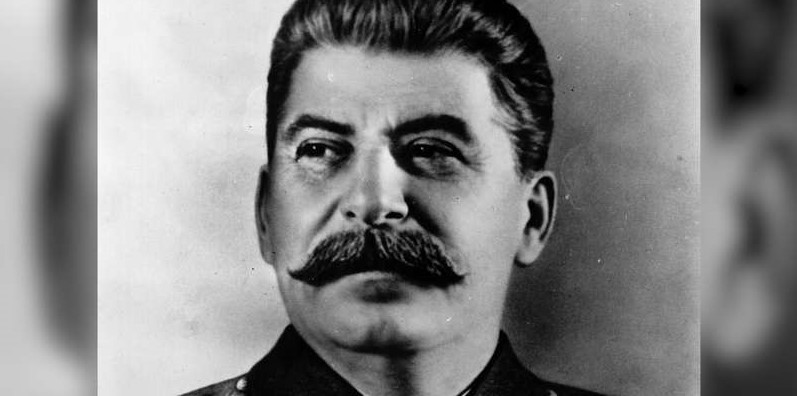

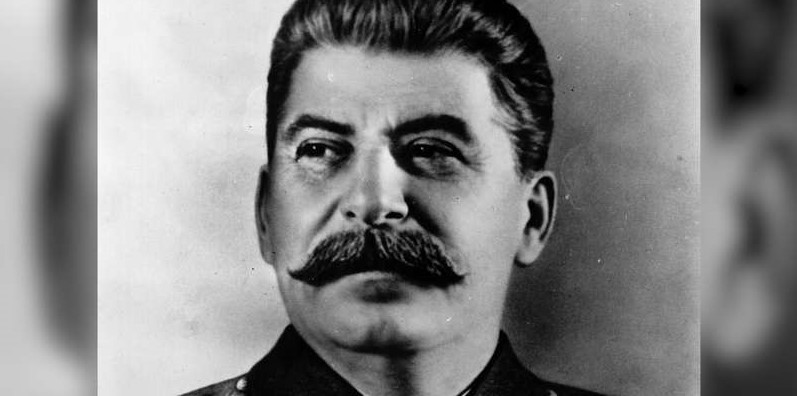

The crimes of Joseph Stalin

The above is a rather sweeping overview of the early history of Stalinism. What is often missed in such narratives is the human cost. In considering the politics of Stalinism, particularly at a time when some young socialists seem intent on rehabilitating the personage of Joseph Stalin, what should not be forgotten is that Stalin was one of the greatest criminals in the history of the Communist movement.

In his suppression of internal opposition, Stalin launched a wave of repression, which led to the expulsion, exile, imprisonment, and murder of almost the entirety of the former Bolshevik leadership. From 1934 onwards, Stalin launched the Great Terror, with mass arrests, murder, and torture. The Moscow Show Trials of 1938-38 saw former Soviet leaders, including Zinoviev, Kamenev and Bukharin forced to confess to ludicrous crimes, supposedly part of a conspiracy headed by Trotsky. Trotsky himself was murdered by a Stalinist agent in Mexico in 1940.

In the Great Purge from 1936 to 1938, around 1.6 million people were arrested and 700,000 executed. The number that died in NKVD torture chambers and concentration camps is still unknown. Ethnic cleansing against national minorities was unleashed. Forced collectivisation during the First Five Year Plan led to mass famine in 1932-3, which led to the deaths of around seven million peasants. Over a million Soviet soldiers who had been German prisoners during the Second World War were interned on their return to Russia. Almost 150,000 residents of the Baltic states were deported between 1945-49 as were 11,000 Georgians in 1951. By 1953, three million Soviet citizens were in internal exile, and 2.5 million imprisoned.

The overall death toll of Stalin’s policies is still debated, but can be reasonably estimated at 9 million deaths, 6 million of which were deliberate killings.

Aside from his role as one of the greatest mass murderers in human history, Stalin was the leader of a counter-revolutionary movement that built a totalitarian one-party state, in which basic democratic freedoms ceased to exist, and a bureaucratic clique was established in power. Furthermore, the Stalinist model of “socialism” was to become the dominant form throughout the world, distorting the theory and politics of Marxism and its revolutionary, emancipatory core.

The Second World War ended up increasing the prestige of Stalinism worldwide because of the Soviet Union’s role in defeating Hitler and occupying Eastern Europe, setting the stage for Stalinist takeovers in Yugoslavia, China, North Vietnam, North Korea and Cuba. The Soviet Union survived and won the war thanks to the heroism of Soviet workers and peasants defending their industries and farms against a fascist and racist imperialist invader and the advantage that that a planned economy gave them. Of course, the aid received from Western imperialists was also vital. But the Stalinist take-overs across Eastern Europe and the world were no return to revolutionary policy. As soon as alliances with the democratic imperialism were restored, the Communist Parties were once again ordered to adopt a social patriotic stance in the allied countries and the Communist International was dissolved. It shouldn’t be forgotten that as the war ended, the USSR helped suppress revolutionary situations in Italy, and France and betrayed a revolution in Greece.

So although the Stalinists defensively carried out revolutions from above in Eastern Europe after the War, the states they created were as far from being soviet (workers council) democracies as was the USSR they were modelled on. The worker’s political revolutions that might have created such democracy – in East Germany (1953), Hungary (1956), Czechoslovakia (1968), Poland (1981) and China (Tiananmen Square 1989), were violently suppressed. In the end the Stalinist bureaucracies in China and the USSR restored capitalism, as Trotsky had predicted would happen if there was no proletarian political revolution to overthrow the bureaucracy.

What is Stalinism?

With the establishment of Popular Frontism, Trotsky concluded that the Stalinist parties had become reformist organisations, on the side of capitalism against workers’ revolution:

The definite passing over of the Comintern to the side of the bourgeois order, its cynically counter-revolutionary role throughout the world particularly in Spain, France, the United States and other “democratic” countries, created exceptional supplementary difficulties for the world proletariat.

Stalinist parties have historically been similar to social democratic and labour parties. Where they have developed into mass organisations, they have had a working-class membership and voting base, but their leaderships and programmes remain reformist and dedicated to a parliamentary road to socialism and the preservation of capitalist private property. Their roots are often firmest in the trade union bureaucracy, where they play a conservative role. Time and again, such as in France 1968 and Chile in 1970-73, Stalinist parties have made themselves the attack dogs of capitalist states against the revolutionary left.

Along this are many features of political theory and practice that accompany Stalinism’s uniquely counter-revolutionary role – an aggressive, almost pathological hatred and distrust of Trotskyist organisations (in many historical situations taking the form of open violence); an authoritarian model of political organisation; the use of bureaucratic methods within the workers’ movement to stifle opposition; the habit of denunciation and fabrication as opposed to honest political debate.

After 1956, following Nikita Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech”, in which he denounced many of Stalin’s crimes and the personality cult of Stalin, it became official policy of the Communist parties to distance themselves from the “excesses” of the man himself, while remaining loyal to the bureaucratic one-party state he established. This turn in many ways solidified the reformist character of the official Communist parties, ensuring they pursued “peaceful coexistence” with the capitalist West, and didn’t scare bourgeois elements with uncritical celebration of the perpetrator of the Great Purge and forced collectivisation. The essentially counter-revolutionary nature of Stalinism remained, proven by the repression of the Hungarian Revolution that year.

Stalinism without Stalin, therefore, came to be the official position of the Communist parties, including the Communist Party of Great Britain, predecessor to the CPB.

Britain’s Road to Socialism

Stalinism in Britain never achieved the mass character it did in other countries. The historical weakness of Marxism in the British working-class and the dominance of Labourism, rooted in the trade unions, meant it was relegated to a minor role. After the twists and turns of the 1930s, it largely settled into the habits of a ginger group to the left of the Labour Party and the trade union bureaucracy.

It outlines its firmly reformist politics in its programme, Britain’s Road to Socialism. First published in 1951, it has gone through many versions, all of which retained the same key fetures. Britain’s Road to Socialism is in fact probably one of the clearest blueprints for reformist socialism one might find on the British left. As such, it makes the argument for a path to socialism via the election of a left government based on a cross-class alliance, including “progressive” capitalists. The CPB and its fellow travellers were amongst the most vocal supporters of the Corbyn leadership but failed completely to push for anything like a mass workers’ movement, let alone revolutionary politics.

If at all active in the British labour movement, one is likely to come across any number of left Labour activists and trade union officials whose views reflect the politics of Britain’s Road to Socialism. This, however, does not suggest that the Communist Party has shaped labour movement politic, so much as the Communist Party’s programme simply reflects the outlook of Britain’s labour officialdom – the primacy of elections and parliamentary politics over workers’ mass movements, alliances with the “progressive” capitalists over class struggle, petty nationalism over international solidarity. The CPB’s programme not a road map to socialism, but rather a path of endless compromise in politics and in principles.

Whither YCL?

Given this reformist approach, it is therefore not surprising that there are a growing number of young Stalinists who are disdainful of their mother party and want to take a more radical stance. The juvenile use of ultra-Stalinist imagery and rhetoric to express that impatience can mostly be put down to their mis-education by the Stalinist cadre, rather than a genuine desire to unleash concentration camps and mass purges.

However, this is the essence of the problem that faces most left-right splits in the Stalinist movement, as the Stalinist tradition offers a choice between sectarian ultra-leftism of the Third Period variety or the class collaboration of Popular Frontism. In the 1960s and 1970s, Maoist organisations emerged as a reaction to the bureaucratism and reformism of the official Communist parties, with many looking towards China as a revolutionary alternative, with Mao’s emphasis on armed struggle and Cultural Revolution. The Stalinist and social democratic parties were denounced as “social fascist”, and these sections of the Stalinist movement set off towards ultra-left dead ends.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Stalinist movement faced a major crisis. Those most critical of the Stalinist tradition, the so-called Eurocommunists, made up the right of the split in Britain, abandoning even the pretence of revolutionary politics (many of its proponents became supporters of Neil Kinnock and Tony Blair). The precursors of the CPB were in fact the left of that split, as they clung to what remained of socialist politics in their programme along with their nostalgia for the Soviet Union.

Splits between Stalinists usually lead nowhere. Rejections of Stalinist ideology tend to go hand-in-hand with an abandonment of Marxism altogether, while “left” turns decline into sectarian isolation. Underpinning both of these patterns is the equation of the legacy of Stalin and Stalinism with Marxism and revolution, which of course is a product of miseducation on the part of Stalinist organisations. Any split by the YCL is therefore unlikely to produce anything other than yet another ultra-Stalinist sect doomed to sectarian isolation as it trumpets its veneration of monstrous historical figures as a sign of revolutionary purity. Meanwhile, the CPB will likely continue to amble down the path of geriatric left reformism.

We put forward this analysis in the hope that more critically minded socialists in or around the CPB and YCL who witness these convulsions may recognise the dead end that Stalinist politics has become, and instead look for a truly revolutionary alternative.