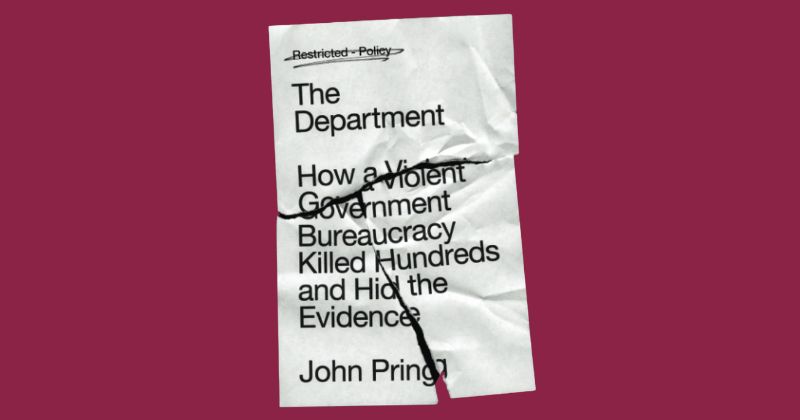

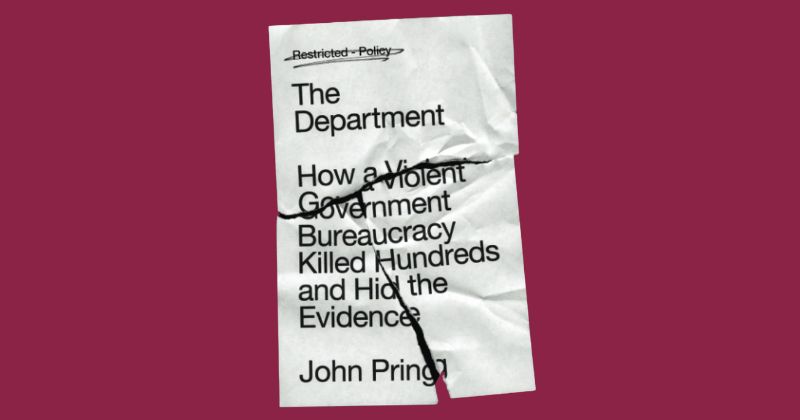

REVIEW: The Department: How a Violent Government Bureaucracy Killed Hundreds and Hid the Evidence by John Pring, Pluto Press, 2024

By Matthew Smyth

Michael O’Sullivan, a builder from London, worked hard all his life, until severe mental health issues made that impossible. At the age of sixty, he was diagnosed with depression, and after attempting suicide, his GP signed him off work. He was claiming incapacity benefit at the time, but his support was quickly cut short. This was 2013, and the Tory – Lib-Dem coalition was enacting sweeping austerity aimed at cutting back disability-related benefits.

Michael was called to attend a Work Capacity Assessment (WCA). These involve poorly-trained assessors working for an outsourced firm like ATOS, determining someone’s ability to work on the basis of a 30-minute interview. The assessor was not even aware he had been placed on sick leave for his mental health, and did not request reports from his psychiatrist, or to hear testimony from his family. From this one conversation, Michael was assessed as fit to work.

What work is there going for a 60-year-old former builder? His mental health worsened due to the stress of finding work. His GP put him on a waiting list for therapy – but with the abysmal state of mental health provision in the NHS, his first appointment was six months away. By that point, Michael had already taken his own life.

Unfortunately, Michael’s death is not an isolated incident, as evidenced by John Pring’s well-researched book The Department: How a Violent Government Bureaucracy Killed Hundreds and Hid the Evidence. John Pring is founder and editor of the Disability News Service. He has chronicled the scandalous extent of oversight, negligence and what he terms ‘slow violence’ in the Department for Work and Pensions policy.

The Department’s strength as a book is its meticulously documented account of the developments in the system that have led it to be so unfit for purpose (in fact, deliberately so, as the whole point is to have as few people claiming benefits as possible).

This book is an important, but very difficult read. Pring tells the stories of 12 bereaved families and their quests for justice, which underpins a broader overview of Britain’s pernicious benefits system. Pring’s career as a disabled journalist and his involvement in Disabled People Against Cuts (DPAC) enable him to also describe the anti-cuts movement which disabled people led in response to the cuts.

What Pring terms ‘slow violence’ from the DWP – people dying because the sustained assault of harassment, stress, poverty and degradation leads them to suicide or starvation. Engels described this process in his 1845 work The Condition of the Working Class in England. He coined the term ‘social murder’. While conditions have changed for the English working class since then, the inexorable logic of capitalism remains the same:

‘When one individual inflicts bodily injury upon another such that death results, we call the deed manslaughter; when the assailant knew in advance that the injury would be fatal, we call his deed murder. But when society places hundreds of proletarians in such a position that they inevitably meet a too early and an unnatural death…knows that these thousands of victims must perish, and yet permits these conditions to remain, its deed is murder just as surely as the deed of the single individual.’

Pring’s decision to anchor The Department in individual stories is an effective one. The cruelty of the system is laid bare, and it’s a stirring call to action to defend the rights of disabled people, especially now as the Labour government plans to introduce £5 billion cuts to disability-related benefits and ‘get Britain working.’

We must ceaselessly combat that the prevailing dehumanising narrative surrounding benefits claimants as work-shy, fakers, scroungers etc. Pring cites a focus group used by the government in 2011, which found that members of the public polled believed that 70% of benefits claims were fraudulent. The actual figure: less than 2%.

It’s essential that we counter this narrative with the simple demand: tax the rich. Tax the rich to pay for decent living benefits for all who need them and proper funding for the NHS to provide physical and mental healthcare equally. But also to fund workplace adaptations and special facilities accessible to all disabled people who want to work, designed by, and under the control of disabled workers and their trade unions.