By Svenja Spunck

IN June, the Russian government announced a far-reaching pension “reform”. The main change is to raise the retirement age for women from 55 to 63 and for men from 60 to 65. What may sound to people in Germany like whingeing actually means working to the death in Russia, because average life expectancy is 65 years.

It is no coincidence that this reform was announced during the World Cup. Following the old “bread and circuses” principle, it was hoped to announce the changes while the population was distracted and enjoying the spectacle. But, although protests were initially banned for “security reasons”, popular dissatisfaction was unleashed in the first major, nationwide protests as soon as the World Cup was over.

In Russia, retirement does not at all mean that people no longer work. Pensions are just a small financial support, around 120 euros, which is paid to older workers. As many as 14 million people above retirement age are currently still employed in their jobs. The increase in the retirement age will mean even more people in precarious conditions and the impoverishment of the older sections of the population, but it also has the potential to raise overall unemployment.

The minimum wage in Russia, after Putin adjusted it to the subsistence minimum at the beginning of this year, is 11,000 rubles (139 euros) a month. Poverty is also widespread among the working population. Around 5 million people live on this minimum income, despite having full-time jobs.

On the grounds that the government must make savings that it allegedly wants to invest in other social areas, the already low pension budget is now to be cut. It is no secret that Russian oligarchs are among the richest people in the world. However, it is also crystal clear that they are well integrated into the state bureaucracy and that no one there would ever dream of touching their assets. While there is money for the military, state surveillance and mega-construction projects, the population is supposed to swallow neoliberal reforms.

Pension reform was not mentioned at the time of the presidential election last March 2018. Clearly, Putin realised that such a measure would not meet with great approval. This was then confirmed by a drop in his standings in opinion polls as soon as the plan was announced. Initially, the Kremlin’s strategy was to blame the Duma, the Russian Parliament, for the reform. After a month of silence, during which discontent grew and became more obvious, Putin announced that he, too, had criticism of the reform and would ensure that it was revised again. Subsequently, he has announced that the pension age for women will “only” be raised to 60.

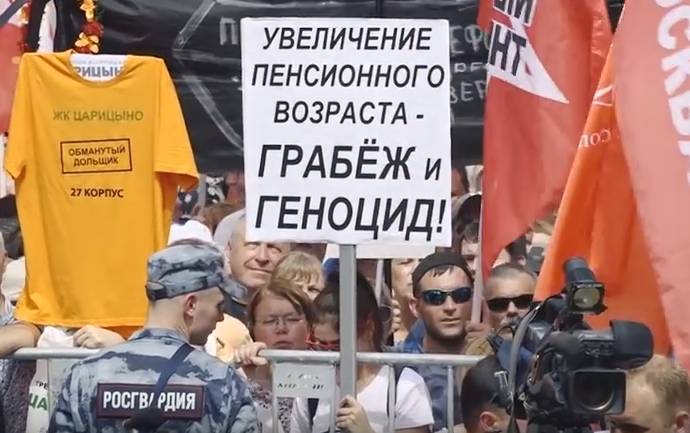

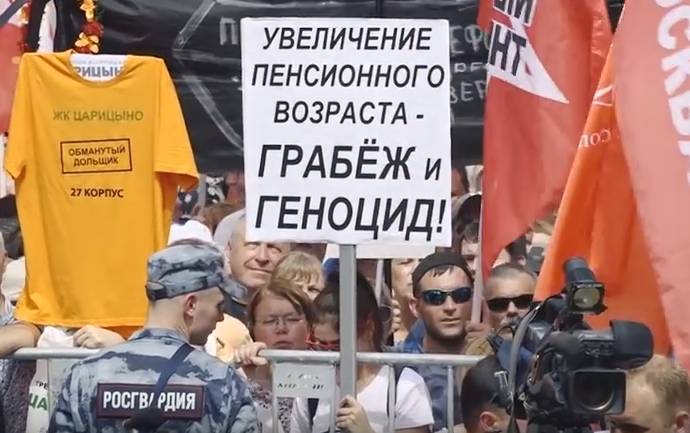

While the ruling party, United Russia, is acting as if there were disagreement about the plan, opposition has begun with the first protests. While the right-wing, neoliberal oppositionist Alexei Nawalny also called for a demonstration against the reform, in reality it is the forces supported by the working class that dominate the protests. At the end of July, around 12,000 people in Moscow responded to the call of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation of Gennady Zyuganov. There were also protests with several thousand participants in other Russian cities. During the demonstrations the resignation of Prime Minister Medvedev was demanded and Putin was called a “thief”. In addition to the CP, which in recent years has consistently acted as the regime’s loyal opposition, a large spectrum of left-wing organisations took part in the actions, even extending to social democracy. Some participants and organisers were arrested. The anti-terror police unit, the “Russian Guard”, was also present.

In the autumn, the pension reform is to be discussed again in parliament and the protests are expected to continue. Because of the strong repression against trade union and political organisation, the Russian working class only has limited experience of militant protest and organisation. But the protests of recent weeks, in which youth and women’s organisations also took part, clearly show that the left is on the way to a united front against the neoliberal attacks.

The extension of the protests could not only prevent the reform, but also help to build up a left-wing opposition. The issue of pension reform and its widespread rejection provides a good basis for tackling other problems of Russia’s ruling politics. The demand for government resignation has already been raised. In order to reach large sections of the population, the demand for the expropriation of the oligarchy and the introduction of a minimum pension that covers the cost of living and is automatically adjusted for price increases should also be raised.

The demonstrations and actions are an encouraging example and show that even Putin’s rule is not unshakeable. What could be decisive is whether the protests go beyond demonstrations to a political strike movement that can bring the country to a standstill.