By Dara O’Cogaidhin

Nato, despite its huge military superiority, presents itself as a defensive alliance, as ‘the good guys’, whose wars are always humanitarian and in defence of democratic values. Yet for two decades it hardly faced any adversaries – Russia was prostrated, and China a major economic partner of the United States. In those years many commentators asked, ‘Why does NATO still exist?’

Manufacturing a new role

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the US and Britain faced major challenges: how to justify a Nato alliance whose ostensible purpose had been to defend Western Europe from an enemy that no longer existed? And how to even expand it while justifying keeping Russia out?

For the US, Nato was necessary to ensure its continued influence in Europe, blocking moves towards a more independent foreign policy or the creation of an independent European military force. This was a delicate balancing act, as a 1992 Pentagon document spelled out, of accounting ‘sufficiently for the interests of the advanced industrial nations to discourage them from challenging our leadership’.

US president George Bush Senior moved swiftly to ensure Nato’s continuation. American government archives show his Secretary of State promising in 1990 that Nato would not be extended ‘one inch eastward’, in exchange for Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s acceptance of a reunified Germany within Nato. The same archives show that US officials almost immediately began plotting to do the exact opposite, while publicly proclaiming ‘cooperation’ with Russia and an ‘inclusive Europe’.

Russia dissolved its rival Cold-War military alliance, the Warsaw Pact, a year later. This alliance was created by Stalin as a buffer zone against any repeat of the invasions that occurred in two world wars. This zone had been agreed at the Yalta and Potsdam conferences as the war ended. In tandem with the development of modern Russian imperialism, the former buffer zone has been relentlessly stripped away and incorporated into Nato, stoking the insecurity of Russia’s new capitalist rulers.

In 1994, President Clinton announced plans to expand Nato, a plan which had already been secretly discussed with the new capitalist leaders of Poland, the newly formed Czech Republic and Hungary. Russian President Boris Yelstin angrily stated that his government would not accept Nato membership for Poland without simultaneous admission for Russia, and later that Nato expansion ‘will mean a conflagration of war throughout Europe for sure’.

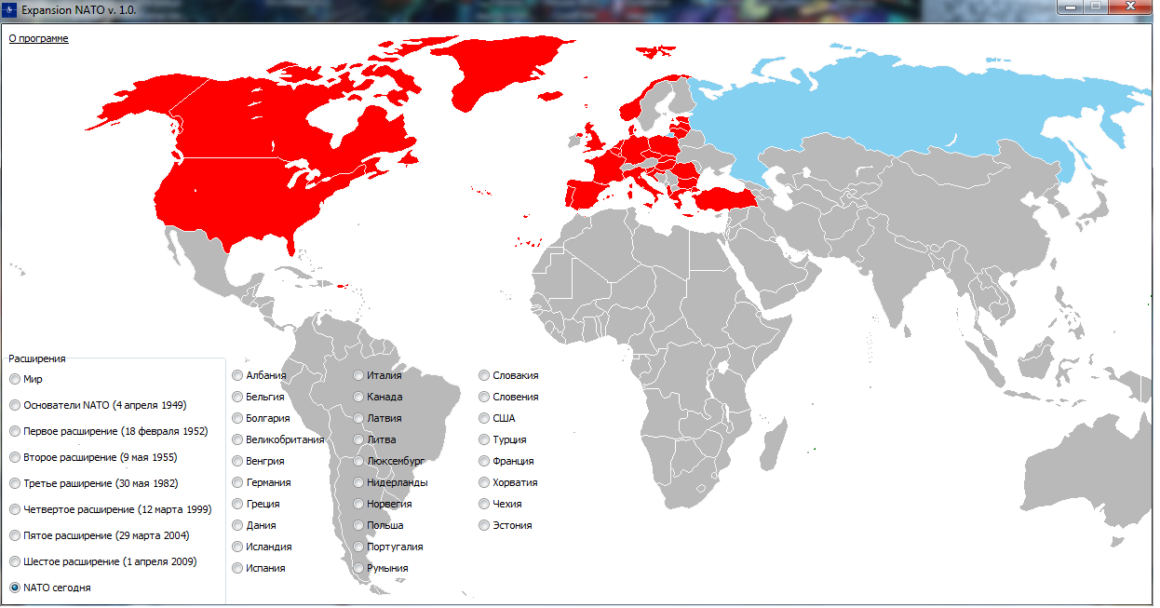

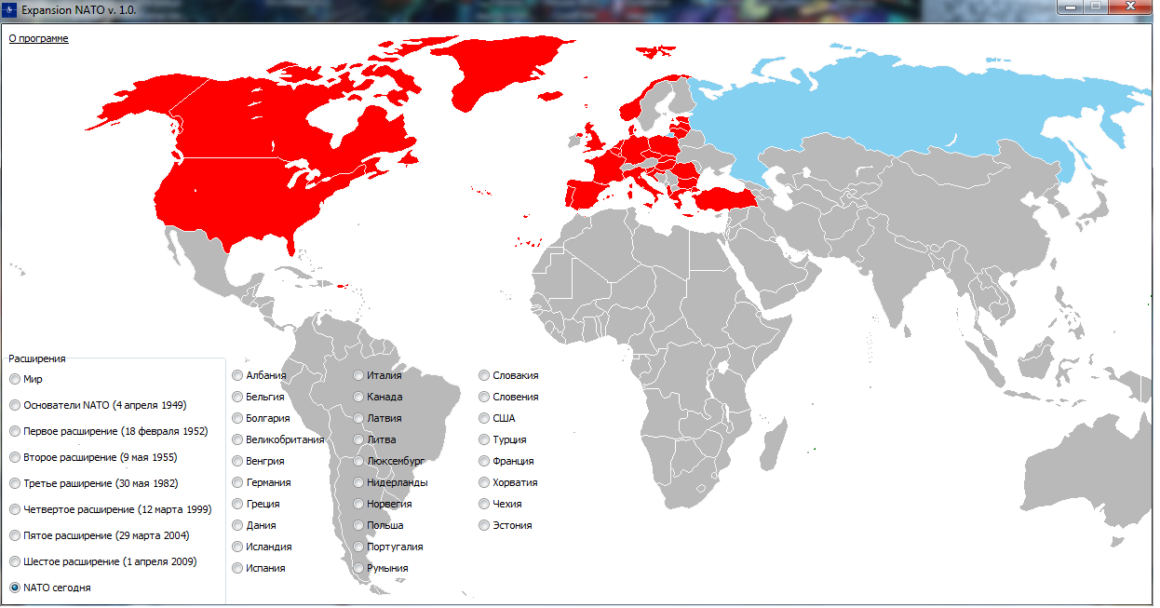

Nato ignored this and moved ahead with its expansion plans nonetheless, with the three countries joining Nato as the first new members from former Warsaw Pact countries in 1999. By the mid-1990s, a consensus had emerged in US foreign policy that the alliance needed ‘to go out of area or out of business’, which necessarily meant moving into previous Russian spheres of influence. Waves of expansion followed, doubling Nato in size and advancing it right up to Russia’s borders, with fourteen new member states from the old Eastern Bloc, USSR and Yugoslavia.

Nato goes to war

Expansion went hand in hand with war. Nato’s first military operation was supporting UN operations with airstrikes in the Bosnian 1992-1993 conflict. But, during the 1999 Kosovo war, China and Russia vetoed a US resolution at the UN Security Council to authorise Nato air strikes on Serbia, a traditional Russian ally.

Nato ignored the decision, arguing it was exercising its right to collective self-defence and espoused a new doctrine of ‘humanitarian intervention’ to justify ignoring the UN – showing international law is interpreted by those with the power to make it.

Riding a wave of public outrage about Serb leader Slobodan Milosevic’s bloody repression of the Kosovars, for 78 days Nato rained bombs on Serbia, hitting trains, hospitals, a TV station and the Chinese embassy. One airstrike killed at least 60 people in a refugee convoy. After Kosovo, Nato expanded its remit further with ‘out of area’ operations in Afghanistan, which saw thousands of Nato troops occupying the country.

Meanwhile, after being elected in 2000, Putin publicly stated he wanted to rebuild relations with Nato, even saying in a BBC interview that he was willing to consider Russia joining Nato. However, as the US and Britain would never allow this Nato expansion continued, with EU enlargement in its wake. The EU and Nato were not just intent on absorbing Europe to its furthest bounds, they wanted to force Russian influence out.

Nato operations went alongside other more aggressive US interventions, such as the US sponsored ‘colour revolutions’ in Georgia and Ukraine in 2003 and 2004 respectively. These ‘revolutions’ were in fact movements manipulated by the ruling-class in order to turf out Russian-oriented governments, and reorient their economies towards the EU and Nato.

These states would then go on to become Nato ‘partners’, implementing military reforms and regularly holding joint exercises with Nato troops. Georgia and Ukraine joining Nato would complete the surrounding of Russia’s southern European borders, even threatening its access to the Black Sea.

Putin stated categorically that this was a red line, condemning this ‘serious provocation’ at the 2007 Munich Security Conference: ‘Nato has put its frontline forces on our borders: against whom is this expansion intended? And what happened to the assurances our western partners made after the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact?’

The 2008 Nato summit in Bucharest, Romania voted against offering Georgia and Ukraine a membership action plan, pushed for by the US, but agreed a compromise to review this in December. An emboldened Georgia went to war over South Ossetia in August 2008 and Russia invaded the region, expelling Georgian troops. In a tit for tat move that defines the increasing polarisation in the region, the US then put a missile defence system in Poland, with a radar in the Czech Republic.

Ukraine: From hotspot to invasion

The immediate trigger for the Ukraine crisis in 2014 was not Nato enlargement, but an EU plan to pressure the Ukrainian government to sign its Association Agreement in November 2013, an economic threat to Russia since it would apply EU neoliberal rules to the old industrial base of the Donbas and potentially sever its still existing economic ties to Russia.

Putin used leverage, both offers of financial assistance and threats of economic reprisals, to pressure Ukraine to reject EU membership. Financial tightening by the US Federal Reserve Bank triggered a debt-servicing crisis in Ukraine. The Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovich announced he would not sign the EU Association Agreement and instead accepted an aid package from Russia, sparking the Euromaidan movement and coup in Kiev.

The new regime then pushed for membership of the EU and Nato that would instead mean opening Ukraine to exploitation by Western imperialism. This, and persecution by Ukraine’s fascist movement, sparked mass opposition in the South and East of Ukraine resulting in the so-called breakaway regions in the Eastern Donbas, and the Russian annexation of Crimea. The result was a civil war that resulted in 14,000 deaths and over 2 million refugees. The Ukrainian government is committed to Nato and the EU and is determined to take back the Donbas, whatever the human cost.

Socialists and anti-war activists in the imperialist countries (including Britain, Russia, and the US) can best offer solidarity with the working people of Ukraine by building an international anti-war movement against the war-drive of all the imperialist countries. The interests of the working-class in the UK, Russia and Ukraine demand that neither of the imperialist powers be supported. In the West, it is crucial to call for the disbandment of Nato, the withdrawal of all Western armed forces stationed in Eastern Europe, and an end to all Nato arms shipments to Ukraine, in order to begin dismantling the imperialist and capitalist system that breeds war.