By Chris Clough

In the first week of May, 85 years ago, the tragic end to the Spanish revolution played out on the streets of Barcelona as once again the working class set up barricades against the gathering counter-revolution.

They demanded their leaders protect the tremendous gains won when the workers rose up less than a year before against the coup of General Franco. This contradictory dynamic, workers’ heroic initiative coming up against the betrayal of their traditional leaders, reformist and anarchist alike, was a feature of the revolution from its outset.

The Revolution is overshadowed in the history books by the civil war (1936-9) that was intimately bound up with its fate. It is rich in lessons for today’s struggles, revealing the dead-end of alliances with the bourgeoisie, the counter-revolutionary role of Stalinism, the inability of anarchism to complete a revolution and the importance of building a revolutionary party. But more than anything it stands as an epic monument to the ability of the working class to transform society.

Spain of the 1930s was deeply polarised with millions living in extreme poverty. A fallen empire, Spain was heavily reliant on a backwards agriculture, with the worst land distribution in Europe, alongside a rotten state propped up by a reactionary military officer caste and 80,000 religious ideologues who controlled social life.

The great contradiction was the inability of capitalism to solve the land question. After years of swings between liberal and reactionary governments, radicalised workers and peasants elected the left wing Popular Front government in 1936, a cross-class alliance of bourgeois, radical and the workers’ parties. The capitalists turned to fascism as their only way to safeguard their power.

Revolution

The revolution broke out in July 1936 when General Franco, supported covertly by Britain, declared a coup against the Popular Front government. This would have been the end of Spanish democracy as the government, despite being abandoned by the bulk of the ruling class, suppressed news of the uprising and refused to arm the workers.

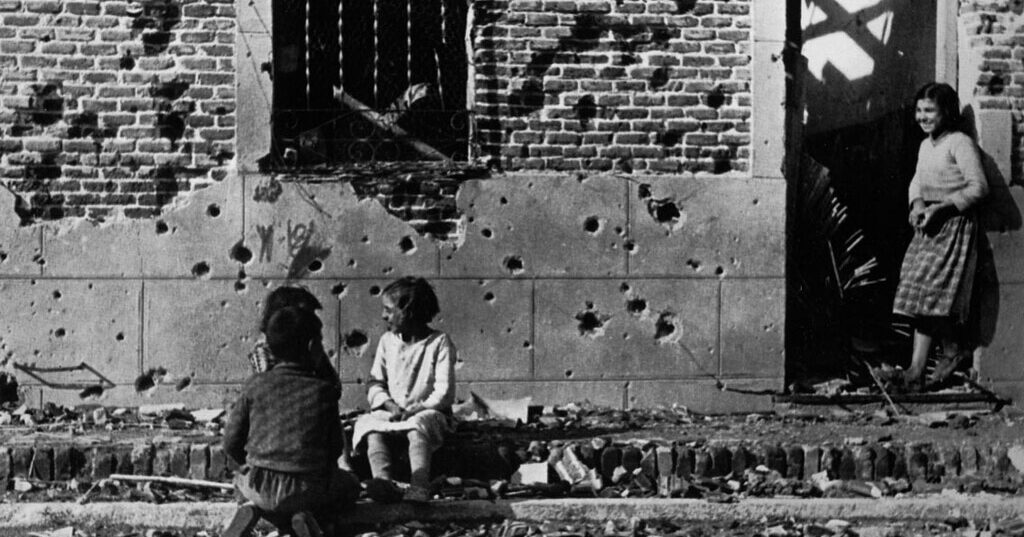

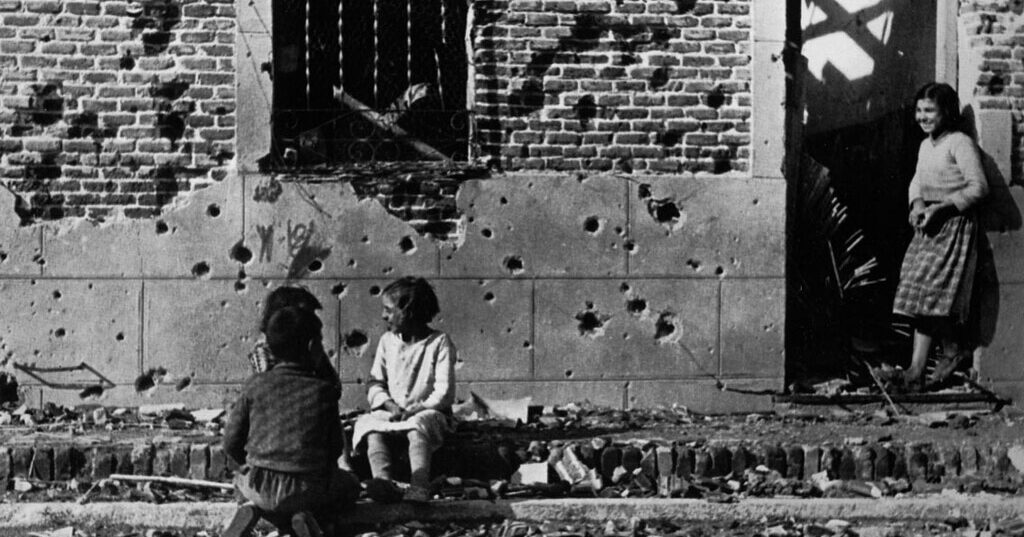

Thankfully the workers, recognising the danger, came out onto the streets in their millions. They raided police stations and seized arms, fighting with knives, clubs and dynamite. Street by street, town by town, they heroically defeated the coup in two-thirds of the country.

The working class became the supreme power in society. The police and military were dissolved, while capitalists abandoned their factories to flee to fascist territory. The revolution reached its highest development in Catalonia, where all industry and agriculture was socialised and the only armed force was the working class militias.

Everything, from food distribution to communications, was run under the control of democratic committees of the working people. Within a few days armed battalions marched upon neighbouring Aragon and drove out the fascists in a war of social liberation, spreading the revolution as they went.

However, the workers’ leaders failed to recognise that the war was not one between fascism and democracy, but between fascism and socialism. Parliamentary democracy had burned itself out. Only the socialisation of industry and agriculture under the democratic control of the workers and peasants could move the country out of the dead end it was in.

In Catalonia, where the revolution was at its strongest, controlled by the powerful CNT union, the anarchist leaders failed to carry through the revolution to the end. As anarchists they rejected any state, even a workers’ state, so they refused to centralise the revolution into a democratic, national congress of delegates from the workers’ committees.

But that was the only way to focus the military effort against a well-armed, centralised enemy. Franco advanced and the capitalist Republican politicians in the Popular Front government started slowly to rebuild their own state power. Workers controlled the streets, the factories, the farms – but not the government. These two powers could not coexist for long.

The bosses could only do this with the support of the communist and socialist party leaders. The Russian revolution had finally degenerated into a bureaucratic dictatorship. Under Stalin’s orders the Spanish communist party (PCE) undermined, then attacked the revolution, hoping to tempt Britain and France into an alliance against Hitler by showing the ‘communists’ were reliable caretakers of Spanish capitalism. But the ‘democratic’ imperialists were more terrified of the Spanish workers than Franco and refused to intervene while Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy supported Franco.

Stalinists betray revolution

The Stalinists argued the workers needed to defeat fascism first and hold back the revolution to avoid alienating the bourgeoisie, when in fact only by defending and extending their revolutionary gains could the workers win the war. The workers’ left leaders justified concessions in the name of the war effort.

The anarchist leaders had early on set up an anti-fascist committee with left republicans, a popular frontist government in all but name. Later they would openly abandon their rejection of ‘authority’… and joined the capitalist Popular Front itself!

Feeling confident, on 3 May 1937 the Stalinists tried to seize the strategic, anarchist-held telephone exchange in Barcelona. The workers rose up, and for a week they held the city. Their leaders blocked any help being mobilised from other cities and called for an end to the revolt. Isolated, the workers abandoned the barricades and the counter-revolution was triumphant.

The Stalinists hunted down the left, arresting and killing hundreds, to put an end to the revolution. They dubbed their new regime the ‘government of victory’. Instead they suffered defeat after defeat as a demoralised working class and peasantry saw the new world they had been fighting for betrayed, the gains of the revolution taken back. With the revolution dead, Franco rolled back the republic until victory in 1939.