By Dave Stockton

THE CONFEDERATION of British Industries (CBI), representing 190,000 companies, warned on 18 October that ‘acute’ labour shortages will spread across more and more industries, from construction and distribution to retail and healthcare. And this crisis could last as long as two years.

Though hospitality trades have enjoyed a strong bounce-back, this sector has been one of the most reliant on European workers, who are arriving in far smaller numbers—36 per cent fewer since Brexit immigration restrictions kicked in on 1 January.

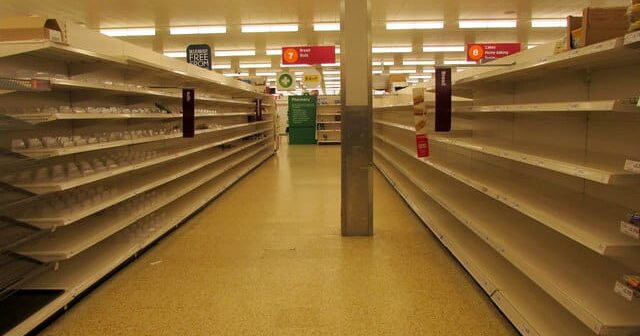

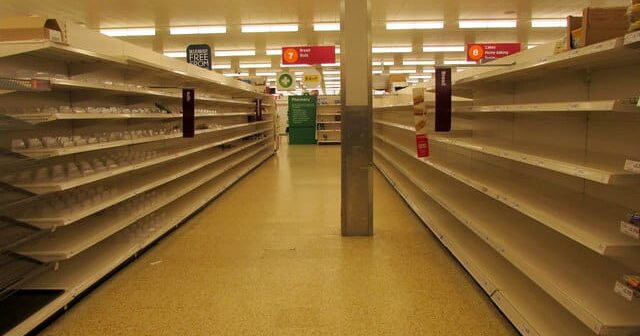

The most striking shortages seen so far are among HGV drivers, which over the summer resulted in panic buying at petrol stations and the need to bring in army drivers. Supermarkets once more had empty shelves and the Tory tabloids screamed about no turkeys for Christmas. The CBI says stock levels fell to their lowest level in 38 years.

Another bitter fruit of Brexit was the shortage of seasonal fruit pickers, forcing farms to destroy vast amounts of produce: so too a shortage of livestock workers, butchers and abattoir workers, which threatened the destruction of tens of thousands of animals. A third of crop growing and harvesting jobs are currently unfilled, according to the National Farmers Union. The National Pig Association reported a backlog of 85,000 pigs for slaughter, increasing by 15,000 each week.

The Tories, with their roots in the shires, sensitive to the farmers’ lobby, responded to their cries for a relaxation of the block on migrant workers, but other were not so lucky.

Carers driven out

In hospitals and care homes, where workforces have been long under pressure, there are more than 100,000 vacancies. Care home labour shortages have soared by around 80 per cent since Brexit. Over 13,000 vacancies were advertised on Totaljobs’ recruitment site in August, a rise of 84 per cent compared to last year.

While EU workers make up 8 per cent of care staff in England overall, areas in southern England have vacancy rates of 25-30 per cent. Most of these posts earn below the £25,600 threshold that allows exceptions for skilled workers.

The National Care Forum (NCF), an association for care providers, surveyed 340 managers in England, employing more than 20,000 staff and caring for around 15,000 people. They reported two-thirds of their facilities now had to cap or stop services, like accepting admissions and offering respite care. This shrinkage of workforces means real suffering for overworked staff after two years of covid stress, as well as for patients and their families, especially for women, on whom the extra caring falls.

Vic Rayner, head of the NCF, called on the Government to pay bonuses to staff, fund a pay increase, and make it easier for migrant workers to fill vacancies. But handouts to private firms and charities are a stopgap solution at best.

Brexit has driven out migrant workers, many of whom—couriers, carers, construction workers, for example—turn out to be key workers for the economy and our communities. Blinded by racist lies from people like Johnson and Dominic Cummings, many workers were fooled into voting for this nationalistic nonsense.

The answer is not to pander to these workers’ racist misconceptions, like Labour’s Keir Starmer and Lisa Nandy do, but to challenge them. The Labour and trade union movement needs to launch a massive anti-racist campaign to convince their members and the wider working class that migrant workers, be they from Europe or beyond, are not competitors for jobs and housing to be shunned, but allies in the fight for decent living conditions for all.

• Open the border – free movement for all

• Full rights and equal pay for migrant workers

• Challenge the racism that divides workers.