INFLATION HAS reached its highest level since the 1980s. The November rate for the UK was 10.67%. Between September 2021 and September 2022, food prices increased by 14.5 percent. At the same time annual wages rises in the private sector stood at 6.7% and 2.9% in the public sector.

The purchasing power of wages has fallen dramatically—and for working class families who spend a higher proportion of their income on food and essentials which have risen faster than the headline rate of inflation, the loss has been even greater. After housing costs, the typical income for a working-age family is set to drop by 3 per cent in the year to the end of March, followed by a 4 per cent drop over the following 12 months.

While some of the reasons for rising prices are beyond the government’s control, its policy of holding down pay is a deliberate choice to reduce government spending and increase private sector profits. Millions of workers are doing the same work for up to 20% less in real terms than a decade ago. Now the government and employers in the NHS, post, and rail are demanding ‘reforms’ in return for miserly pay rises. All this adds up to a major increase in the rate of exploitation.

What is inflation?

Simply put, inflation is a general increase in prices across the whole economy. But what causes this? Some of it results from the reduction of the available raw materials e.g. energy, and agricultural inputs. The war in Ukraine, sanctions, and the post-lockdown economic rebound caused big spikes in the price of natural gas.

Another important contribution to inflation is the increase in the money supply due to government borrowing for the pandemic schemes and quantitative easing to provide cheap credit to private companies. But underlying both factors is a deeper cause—the stagnation in profitable production, the motor of the world capitalist economy.

The central banks’ only effective weapon is to raise interest rates, after a decade of near-zero interest rates, since the near collapse of the banking system in the 2007–08 financial crisis. These increases will push up mortgage payments and rents as well as the cost of borrowing for governments and companies. Turning off the cheap credit taps will force the economy into recession—the Bank of England predicts Britain will enter the longest recession since the war, with 500,000 jobs lost.

The working class of course has no control over the capitalist economy. But in the from of its trade unions and the other organisations which make up the labour movement, it can set itself the goal of preventing or minimising the assault on its wages, its working conditions, its social services, by making the bosses pay the costs of their own system’s crisis.

It is true that unions do put forward claims taking inflation into account, but the long time scales involved mean they are always playing catch-up as inflation gallops away. Worse, they fail to build in protection from future inflation. Multi-year pay deals, and negotiations based on inflation rates many months before leave workers out of pocket before the ink is dry on any agreement.

A sliding scale of wages

There are two further problems. First, unions take the official (CPI) inflation figures as the starting point but this rate has a built-in bias against workers, mainly because it leaves out housing costs at a time of spiralling rents. The Retail Price Index, which Unite has started using, does include mortgage payments but not rent rises, so also falls short, particularly for low paid workers.

Worse, workers get locked into a deal while bosses are free to hit back with further price rises. In fact, this is what the Bank of England predicts. Over the next 12 months, or longer if unions are foolish enough to sign multi-year deals, any gains will be eroded.

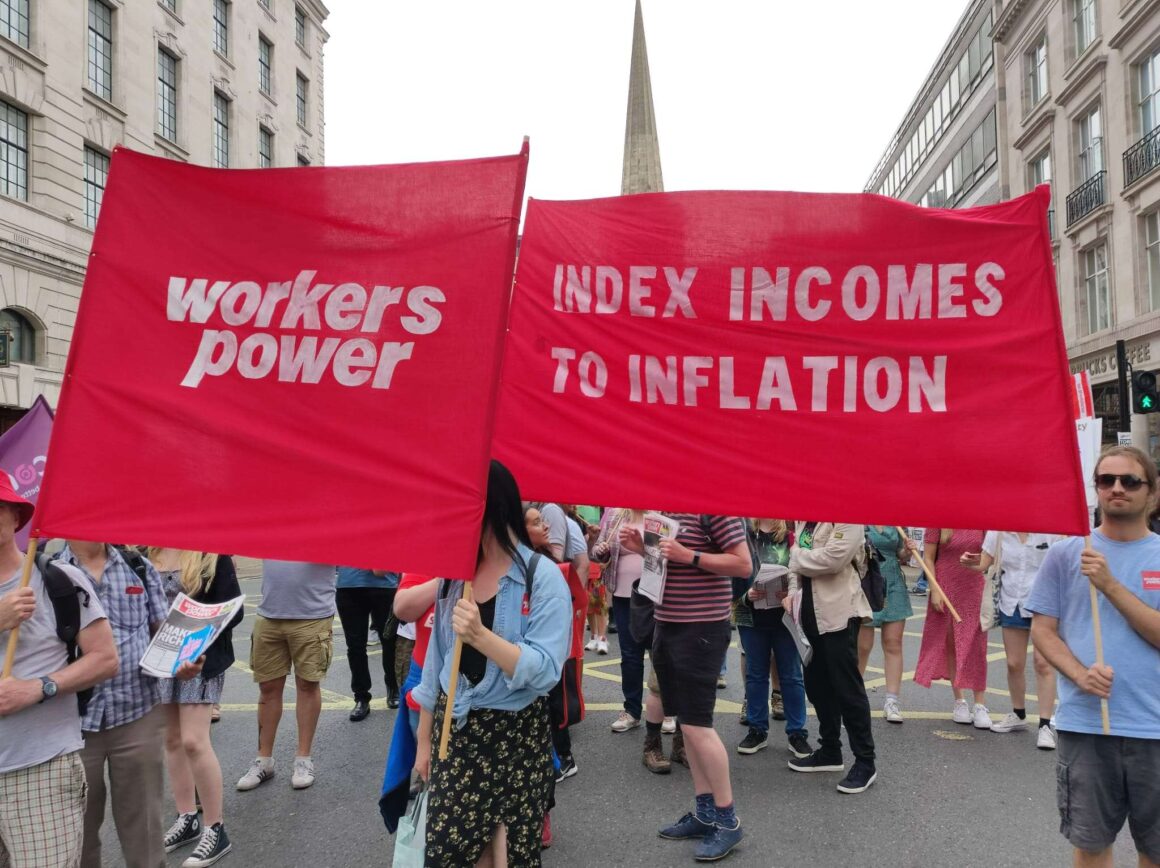

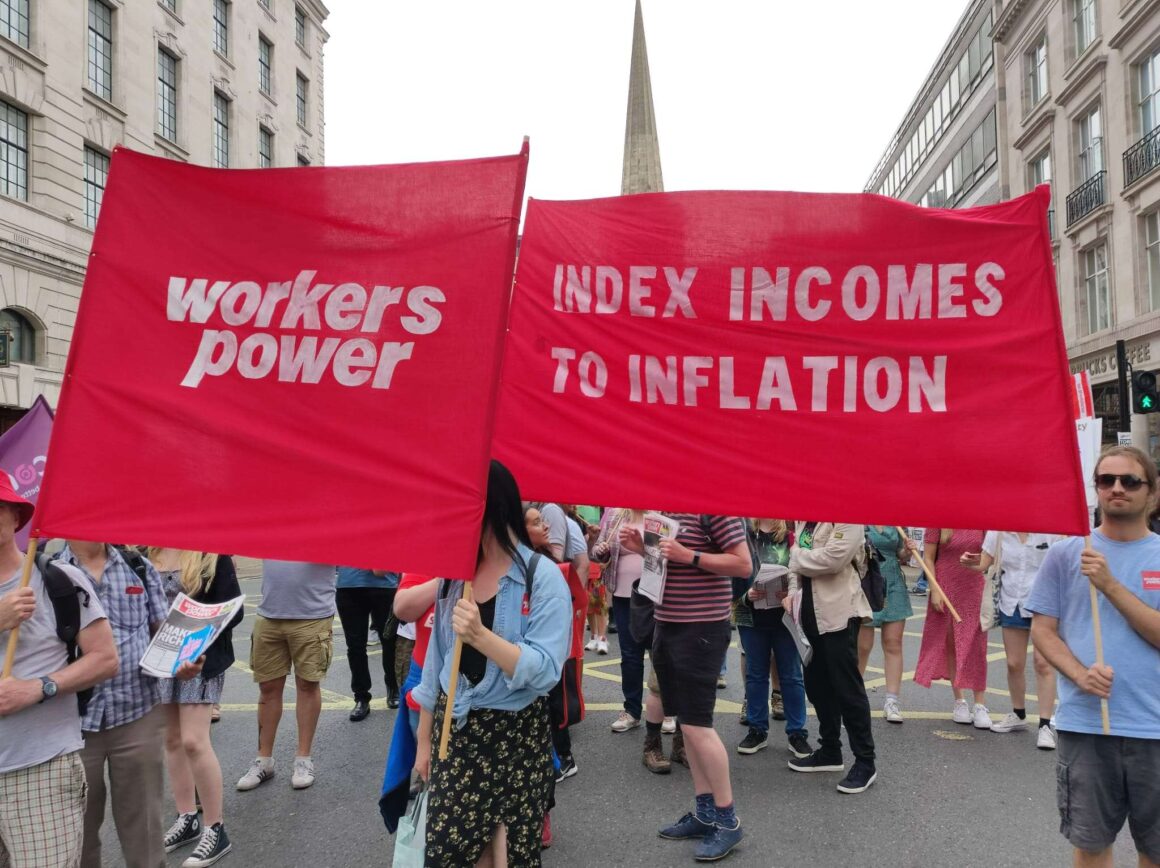

To combat this, workers need to demand a sliding scale of wages. This is a term in the workers’ contract guaranteeing that their wages are linked to a cost of living index so that every rise in the real cost of living leads to an automatic rise in wages.

Some countries like Denmark, France, and Italy have in the past adopted what are variously called “indexation”, ”escalator clauses”, or “automatic adjustment”. Luxembourg and Belgium are the only EU countries that currently practice it. Inflation in the latter country topped 12% in October. In January 2023, nearly one million Belgians can expect a raise as high as 11.59%.

To avoid the dangers embodied in the official inflation rates the unions need to set up price watch committees, which can calculate all increases in their members’ actual living costs.

As we enter the 2023–4 pay round, activists should campaign for their unions to adopt policy mandating all negotiations to include escalator clauses indexing pay to inflation.

More widely, we should campaign for the minimum wage, pensions and benefits to be linked to inflation at a rate calculated by the labour movement.

This is a first step in the fight to defend the living standards of working class people from further erosion, on the principle that we won’t pay for their crisis.