By Bernie McAdam

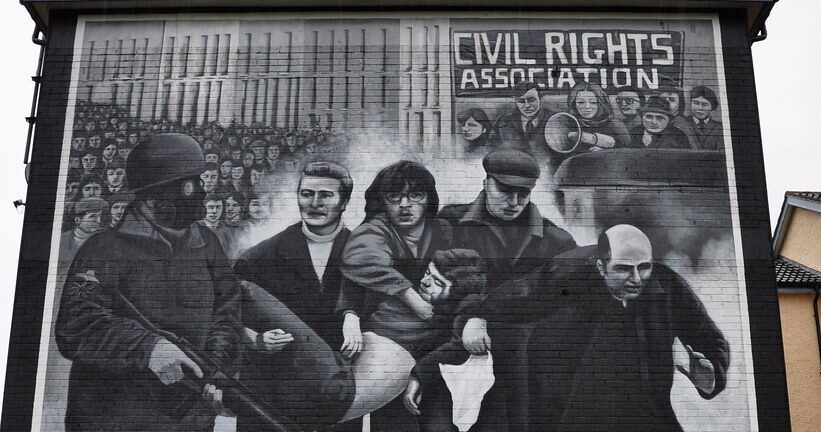

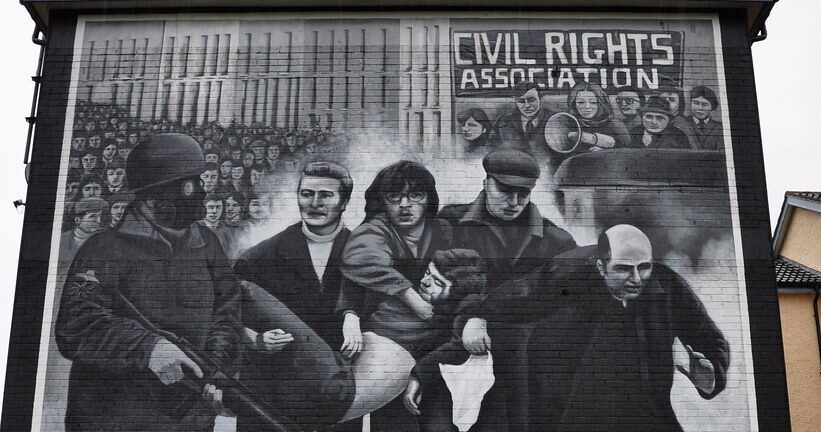

On 30 January 1972, Bloody Sunday, the British Parachute Regiment shot dead 13 unarmed civil rights protesters in Derry (another died shortly afterwards) and wounded 15 others. A Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association march was banned on the recommendation of the British Army; when it went ahead, it was drowned in blood.

Bloody Sunday was a watershed moment, when a struggle launched in 1967 for equal rights by the oppressed Catholic minority went over to a struggle against British rule, the Protestant state and the partition of Ireland. The massacre finally put paid to the myth that the British Army was there to keep the peace between two ‘warring tribes’ and keep them apart. It was a defining moment in alienating the whole nationalist community in the north of Ireland and confirming to them that Britain was not serious about reforming the sectarian edifice of the six county Unionist state.

In the aftermath of Bloody Sunday mass resistance in the North increased. Catholic workers in hundreds of factories came out on strike with impromptu protests throughout the six counties. The Provisional IRA recorded a huge surge in recruitment and escalated its armed campaign. In the Republic of Ireland unparalleled protests took place with three days of strikes and marches in villages, towns and cities across the island. Trades Councils organised protests with whole workplace contingents on the marches. This culminated in a General Strike on the third day when the Bloody Sunday victims were buried.

The British Embassy in Dublin was burnt to the ground and MP Bernadette Devlin, elected on a civil rights ticket, famously punched Home Secretary Reginald Maudling in the face in the House of Commons. Irish building workers also walked off sites in London and Birmingham. Internationally there were protests from New York, where John Lennon attended, to Naples and beyond. Two of New York’s union leaders, representing transport workers and the longshoremen, announced a boycott of British exports.

Army lies discredited after 38 years

The Widgery Tribunal, which took place immediately after Bloody Sunday, was a whitewash, clearing British soldiers of any wrongdoing and claiming they had come under fire. Widely discredited, the British state stuck by it for 38 years. The relatives of the murdered waged a long and determined campaign to expose the truth and finally, in 2010, a new inquiry produced the Saville Report. After 12 years of investigation and hearings, this vindicated the relatives and declared the killings ‘unjustified and unjustifiable’. This merely confirmed what the people of Derry knew already, but it overturned the official version, forcing David Cameron to apologise in the House of Commons.

Lord Saville states that soldiers gave no warning they were about to fire: ‘Despite the contrary evidence given by the soldiers we have concluded that none of them fired in response to attacks or threatened attacks by nail or petrol bombers.’ The order to fire should not have been given. Some of the victims had been running away from the soldiers and were shot in the back. Some were even helping injured victims and none of them were armed. The report also said that soldiers had ‘knowingly put forward false accounts’ during the investigation.

Army press releases on the evening of the massacre all claimed soldiers were under heavy gunfire, a lie but one the bulk of the British press faithfully transmitted. Captain Michael Jackson, second in command on the day, aided the cover-up by producing a ‘shot list’ that turned out to be pure fabrication, with none of the shots described in the list conforming to evidence of shots actually fired. He was rewarded for by eventually assuming the top post in the army.

A few bad eggs?

The Saville Report exonerated the innocent but stopped short of the obvious conclusion that the shootings were unlawful killing or murder – 12 years on and still no soldiers have been prosecuted! It found no conspiracy in the British government or higher echelons of the army to use lethal force. It limited its criticisms to Lt Colonel Wilford, the officer in charge, for going further than his orders warranted and a number of Paras who had lost self-control. So for Saville it all boils down to a few bad eggs.

This draws attention from the role senior figures in the British army and government played on Bloody Sunday and indeed throughout the north of Ireland in this period. Saville heard how Major General Ford, commander of land forces in the North, wrote a memo three weeks before Bloody Sunday: ‘I am coming to the conclusion that the minimum force needed to achieve the restoration of law and order is to shoot selected ringleaders among the Derry young hooligans, after clear warnings have been given.’ General Tuzo, in overall command of the British army in NI, argued that to take control of Derry was ‘a major operation which would involve, at some stage, shooting at unarmed civilians’.

Prime Minister Ted Heath four days later told his Cabinet, ‘a military operation to re-impose law and order would be a major operation necessarily involving numerous civilian casualties’. Clearly the British government had been discussing the civil rights march and its response prior to Bloody Sunday, even sending a memo to the British embassy in Washington warning of hostile reactions if there was trouble in Derry.

Furthermore the same Parachute regiment had already served notice of its murderous intent when 11 unarmed civilians, including a priest, in the Ballymurphy area of Belfast were killed the previous August as part of its operation to intern hundreds of nationalists without trial. A coroner’s report in 2021 found that all the civilians in what became known as the ‘Ballymurphy Massacre’ had been innocent and killed ‘without justification’.

The meaning of Bloody Sunday

So Bloody Sunday was not a one-off incident or aberration, or result of a few rogue soldiers in an otherwise spotless army. It can only be understood in the context of Britain’s occupation of part of Ireland and the sectarian state it helped create and prop up since 1921. The ‘Northern Ireland’ state could only survive by way of systematic social oppression of Catholics with discrimination at every level including housing, voting and jobs. In 1968 Catholics finally said enough is enough and flocked to the streets to fight for civil rights and equality.

They were met with savage attacks from the overwhelmingly Protestant Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and loyalist gangs. When the RUC were driven out of Derry’s nationalist Bogside neighbourhood in August 1969, British troops were deployed to restore control. As troops increasingly took to the streets it became clear to all those struggling for civil rights that the army and their masters in Whitehall, both Labour and Tory, were not going to reform the ‘Orange’, unionist state but prop it up by breaking the resistance to it.

In August 1971 internment without trial was introduced to cut the head off the protest movement. As the army and police rounded up over 350 people, all of them Catholic, several cases of torture leaked out, notably the 14 ‘hooded men’ taken to Ballykelly army ‘torture centre’. This sparked mass resistance, with 8,000 workers holding a one-day strike in Derry, a rent and rates strike throughout the Catholic community and thousands of attacks on soldiers and police. This went alongside curfews, the sealing off of whole areas, mass raids and of course the shootings. As the discussions in the government and army quoted above show, Ballymurphy and Bloody Sunday were part of this general strategy of repression.

Imperialist Britain’s reactionary role

As the entry of British troops in 1969 showed, the Northern Irish state could not exist without Britain’s military power, the mobilisation of Loyalist gangs and paramilitaries, and repressive laws like the Special Powers Act, admired by apartheid ministers in South Africa for its comprehensive, draconian measures.

Partition was Britain’s answer to Ireland’s struggle for independence from the 1916 Easter Rising to the War of Independence in 1921. Disregarding an overwhelming majority for the nationalist Sinn Fein in the 1919 General Election, Britain carved the northern state out for the loyal Protestant minority in the North by threatening all-out war against the IRA. Its leaders betrayed the struggle and acceded to this prison house for Catholics. Integral to NI’s existence was systematic social oppression of this new minority on the basis of their identification with Irish nationalism and a united Ireland. Any challenge to institutionalised discrimination would inevitably rekindle a national struggle.

Today as we commemorate Bloody Sunday and press for full justice to its victims, we are still faced with a dysfunctional state shored up by British force. In a growing state of crisis with Unionists no longer a majority, mounting poverty and the unravelling of Brexit on an island that never wanted it, once again the question of British withdrawal and a united Ireland is raised.

The fight for a Workers’ Republic is the best way we can avenge and remember the brave civil rights protesters who were cut down by the British government and their army on that shameful day. It is also the only way we can build a united Ireland, free of British imperialism and of capitalist governments north and south, one owned and controlled by Irish workers.