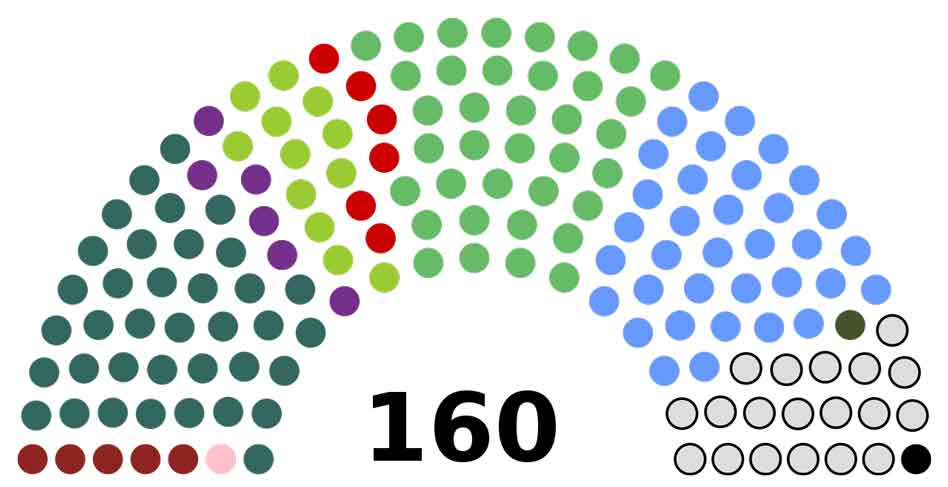

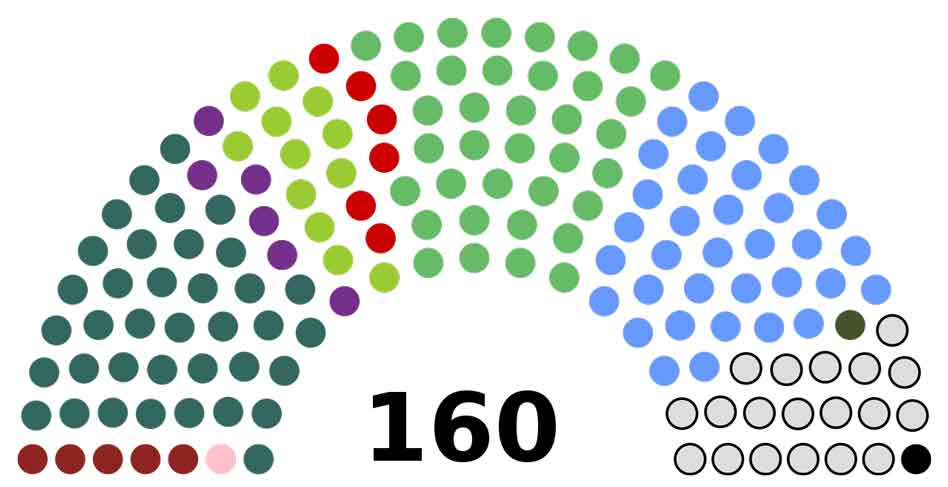

IRELAND’S 7 FEBRUARY election delivered a stunning result for Sinn Fein. They won 24.5% of the first-choice of votes, sweeping away the quasi-monopoly exercised on power for a century by the centre-right parties Fine Gael and Fianna Fail. But the party was pipped at the post by Fianna Fail, who netted 38 TDs (or members of parliament), to Sinn Fein’s 37, thus making them the largest party by number of seats. The leadership of Sinn Fein had so little expectation of this triumph that they presented only 42 candidates for the 160 seats in parliament.

Confronted with an appalling housing crisis and the neglect of public services, voters were won over to Sinn Fein’s programme of arresting austerity and delivering reforms such as rent freezes and construction of low-cost housing. An exit poll suggested there was a strong generational divide at this election. The frustrated housing aspirations of ‘generation rent’ decided the outcome of the election. Around 32% of 18-34 year-olds backed Sinn Fein at the ballot box. The ongoing facilitation of speculative property has added significantly to demand and seen housing unaffordability and homelessness exponentially rise. There were 9,731 homeless people in the week of 23-29 December 2019 across Ireland. This figure includes adults and children. According to the homeless charity Focus Ireland, the number of homeless families has increased by 280% since December 2014.

Draconian austerity

This anger has roots in the financial crash that was set off by the fall of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 and followed by the world’s worst economic crisis since 1929. The Irish economy entered one of the deepest recessions in the Eurozone, with its economy shrinking by 10% in 2009. The government was forced to turn to the European Central Bank, the European Commission and the International Monetary Fund for €67.5bn to finance the budget and recapitalise its banks. Known as the ‘Troika’, these three institutions provided bail-out funds contingent on an extensive range of austerity measures designed to reduce the budget deficit.

By the beginning of 2013, Ireland had become the fifth most expensive country in the EU, with house prices 17% above the European average. The government also introduced a shocking array of welfare cuts that have driven more and more people into debt and poverty. The resulting austerity pushed Ireland to the bottom of the OECD league tables in terms of child poverty, deprivation and inequality. As a result, many of Ireland’s young adults emigrated. Between 2009 and 2013, more than 300,000 people emigrated from Ireland, four in ten of whom were aged between 15 and 24.

Decades of trade union passivity have resulted in low bargaining power for workers and an unusually high incidence of low pay. While the Irish economy has made significant strides forward in recent years, a 2019 report from the independent think-tank TASC found that Ireland possesses one of the highest rates of low pay in the European Union. The report also noted that trade union membership and coverage are comparatively low, and that Ireland ranks 22nd out of the 23 EU countries in terms of labour market protection. More and more in-work families face over-indebtedness and rising non-mortgage debt. It is little wonder then that a national survey carried out by Amarach Research in 2018 found over half of Irish people reported a decline in their mental health as a result of the economic crash, with 14% saying they had thought about suicide as a result.

Rise of Sinn Fein

Taunted by government claims of an economic recovery, workers decided to send a message to the ruling class. After nine years of gruelling Fine Gael rule which saw living standards fall, Fianna Fail expected to capitalise on the mood for change and lead a new government. However, the party’s association with Fine Gael in the confidence and supply deal, propping up the latter in a minority government since 2016, became their Achilles heel. This exposed Fianna Fail to attacks from Sinn Fein leader Mary Lou McDonald who targeted the left-behind of Ireland’s strong economic growth and campaigned on two key issues: the lack of affordable housing and failings in healthcare.

Sinn Fein’s meteoric surge up the opinion polls panicked the establishment. Fine Gael and Fianna Fail both ruled out entering government with Sinn Fein and attacked them on the basis of their past support for the IRA. This highlighted their own hypocrisy as only weeks earlier they celebrated the restoration of the power-sharing executive between Sinn Fein and the Democratic Unionist Party in Stormont. Facing the ignominy of becoming the only Fianna Fail leader never to become Taoiseach, Micheal Martin quickly revised his long-standing opposition to working in government with Sinn Féin when the shock results began to emerge. Martin later backtracked when a meeting of the parliamentary party decided not to enter government formation talks with Sinn Fein.

Riding on a wave of disgust at the government’s attempt to commemorate the Royal Irish Constabulary and the murderous Black and Tans, and in keeping with their nationalist aims, Sinn Fein also promised to secure a public referendum on Irish unity north and south. Their strategic aim has long been to be a part of the government in the north and south to secure such a ballot. But as they know perfectly well it is up to the British government to oblige, and as Nicola Sturgeon can confirm, this is not on Johnson’s ‘to do’ list.

Solidarity/PBP ‘grand coalition’

In the

Westminster elections at the end of 2019, People Before Profit (co-thinkers of

Britain’s SWP) rightly attacked Sinn Fein’s record of implementing Tory cuts in

the Six Counties. During the campaign they placed placards, which stated ‘Sinn

Fein voted for welfare reform’, around parts of west Belfast where they have

built a significant base. In a statement on the Twitter page of PBP Councillor

Matt Collins, he said, “On Thursday don’t vote for parties who supported

welfare reform, vote for the socialist left.” Barely a month later, PBP TDs in

the 26 counties were keen to present an altogether different image of Sinn

Fein.

As part of an electoral alliance with Solidarity (ex-CWI) and its recent split

RISE, People Before Profit stood on a Keynesian platform with demands for

increased public spending, free public transport, a living wage of €15 an hour

and the building of extra affordable housing. Revenue would be raised through

modest tax rises on high earners and closing loopholes to make all

multinationals pay the 12.5% corporation tax – one of the lowest headline tax

rates in Europe. Socialism was now off the agenda.

Fighting a rear-guard action to hold on to their 6 parliamentary seats, SOL-PBP made a direct appeal for a “grand coalition” of the left to be led by Sinn Fein. In a TV debate Richard Boyd Barrett (PBP TD) was keen to assuage the concerns of Sinn Fein, the Greens, Labour and the Social Democrats by reassuring them they would be reliable coalition partners. They also hoped to pick up transfers from those parties to get their TDs re-elected. After the first count most PBP-SOL TDs were in a dogfight to retain their seats. But because Sinn Fein ran so few second candidates, it meant that when their candidates exceed the quota by a large margin, their surplus went primarily to other left-leaning candidates. These transfers helped SOL-PBP to defy the odds and retain 5 of their 6 seats.

Left government illusions

SOL-PBP TDs immediately went on the airwaves to press

Sinn Fein to form a “left government”. Many who voted for Sinn Fein over

concern for housing and homelessness were unaware of their record on the issue

in the Six Counties, where they supported a ‘City Deal’ in Belfast that will

accelerate the privatisation of publicly owned land – all of it previously set

aside for the building of social housing. PBP fought against this in Belfast

City Hall.

However PBP TDs in the South were now pleading with workers to “mobilise on the

streets” – not to bring the country to a standstill like the general strike in

France – but to appeal to Sinn Fein to form a left minority government,

including the Greens and Labour, who brutalised and punished the working class

following the economic crash during their previous stints in power. Any

government would still require an understanding with either Fianna Fail or Fine

Gael, through some form of confidence and supply arrangement that would see

them abstain on key votes from the opposition benches. This underlines the

folly of PBP’s proposal.

Also any ‘left government’ would be confronted with the weakness of Irish

capitalism, its status as a semi-colonial dependency and the threat of capital

flight. Multinational companies account for 90% of Ireland’s exports and use

the country primarily as a base for tax dodging. Employment in manufacturing is

actually contracting annually. This means that Ireland, as the weak link in

European capitalism, is particularly vulnerable to volatile capital flows.

The global financial newswire Bloomsberg responded to the election result by

stating that now “could be a good time to dump the country’s bonds”, citing the

spending promises by Sinn Fein. However, the employers’ federation IBEC

expressed confidence in a “fiscally responsible” Sinn Fein who pledged to

protect the 12.5% corporation tax rate and the profits of multinationals.

Clearly a ‘left government’ would have to defy the Troika and cancel the Euro debt if meaningful reforms were to be implemented but no ‘left’ party is prepared to go down that road.

For now, any fanciful notions of a ‘left government’ have been torpedoed by Labour who refuse to share power with Sinn Fein. Sinn Fein’s Eoin O Broin also poured cold water on the idea stating that it would not be feasible given the numbers in parliament, causing PBP’s Richard Boyd Barrett to lament that they were “throwing in the towel”. Talks between Fine Gael and Fianna Fail are expected to proceed this week about an unprecedented ‘grand coalition’ involving the Green Party. Fine Gael have demanded a rotating Taoiseach (prime minister) role as part of any deal with Fianna Fail. The best outcome for Sinn Fein at this stage is that the talks fail and another election has to be held. Sinn Fein could then run second candidates in seats where they comfortably topped the poll and return strengthened as the largest party. This would likely obliterate SOL-PBP’s presence in parliament.

Mass mobilisation

Socialists in People Before Profit, Solidarity and RISE should argue against coalition with capitalist parties such as Sinn Fein. The radical left draws its strength from mobilising working people to fight for their own interests. The suspension of water charges in 2016, a massive climb-down for the government, was achieved through mass demonstrations, confrontation and non-payment.

Despite the unwillingness of Sinn Fein to endorse the boycott of water bills, the radical left were able to popularise this message and take a lead in organising a broader political fightback. However, the failure to build on this campaign created a vacuum on the left into which Sinn Fein stepped. A similar campaign around the housing crisis, which is an indictment of the capitalist market, could reinvigorate the left and draw new layers of workers priced out of the housing market and the private rental sector into struggle.

Global capitalism has entered a period of instability and stagnation. Economists broadly agree that Ireland, with one of the most open economies in the world, is at greater risk from global trade tensions and that a downturn is inevitable. The impact of Brexit will be devastating as well. Once again workers will be expected to socialise the losses and bear the brunt of the cuts. We are also on the brink of a climate catastrophe which is the most serious crisis that humanity has faced in its entire history. Solutions to these problems require system change, not just government change.

A real workers government would have to challenge Ireland’s capitalist elite and the rake of imperialist backers, Euro, US and British. It would have to repudiate the Euro debt and, unlike Syriza, defy Brussels. Not leave the EU but fight the EU and campaign for solidarity amongst the European working class in the fight for a socialist Europe. Such a government would tax the rich, expropriate the capitalists native and foreign, nationalise the banks and industry with no compensation and under workers control in building a bridge to socialism.

This spectre of socialism will be resisted by the captains of industry no less than the forces of the capitalist state. That’s why a workers’ government would have to be based on armed workers’ councils and held accountable to those councils. Socialists must launch a revolutionary socialist alternative – a new working class party rooted in every trade union, workplace and community which can coordinate struggle and fight for a 32 county Workers’ Republic.