By Tim Nailsea

THERE HAVE been growing calls for industrial action in Britain’s distribution industry.

Nearly 4,000 HGV drivers have responded to an unofficial call for a “stay-at-home day” on 23 August. In my workplace, a multinational logistics company which services a major supermarket chain, drivers organised by Unite recently voted by a whopping 96.7% on a 77.1% turnout in favour of strike action.

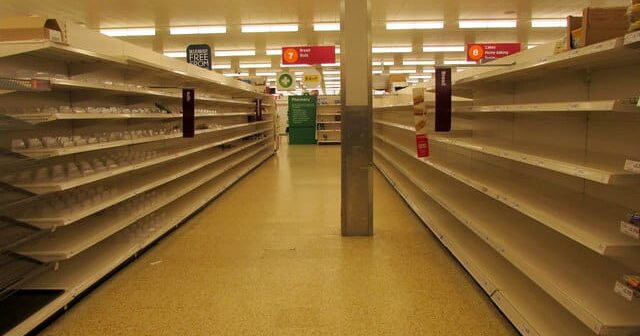

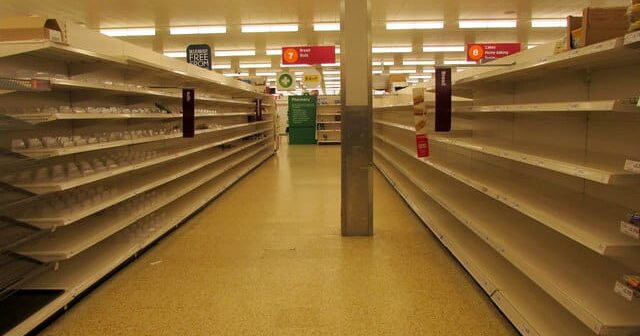

Shortages

The ‘just-in-time’ nature of Britain’s delivery network makes it especially sensitive to changes in the availability of labour. The so-called ‘pingdemic’ has required many distribution workers to isolate at home, including drivers, warehouse workers and administrative staff. Supermarkets and logistics companies panicked in response, offering pay rises and bonuses to attract drivers, easing qualifications requirements, and telling workers that they don’t need to self-isolate, while pressuring the government to waive working time restrictions on drivers.

This is part of a general labour shortage across multiple industries—there are now nearly one million unfilled vacancies across the UK. The pandemic has slowed the supply of migrant labour from overseas, and has also reduced the numbers of workers willing to change jobs or retrain.

HGV drivers are skilled workers and have therefore historically been a relatively well paid section of the working class. They also have a strong trade union tradition and their central role in British industry and commerce has lent them weight in negotiations. However, they have not been immune from the general erosion of pay and conditions that British workers have been subjected to in recent years.

This has caused many drivers to leave the industry and made recruitment more difficult. Brexit has also created problems as the industry has a high proportion of EU workers. While those who have settled in the UK chose to remain, the regular influx of new or temporary migrant workers has reduced, with many finding it easier or more attractive to seek work elsewhere.

The pandemic has made problems worse. The ageing workforce was expected to go into work throughout lockdown, in large workplaces with hundreds of staff, causing Covid-19 to spread quickly. Many became ill or needed to isolate, leading to increased hours, stress and management pressure.

Essential

This has highlighted just how important distribution workers are to the effective running of the economy. Anger at our treatment during the crisis and prior to it has been accompanied by a growing recognition of our industrial power. This combination has the potential to produce a truly powerful militancy.

Distribution workers are not alone in this—there are labour shortages in many key sectors of the economy: in manufacturing, construction, the NHS and, most acutely, hospitality, where approximately one quarter of workers employed before the pandemic have not returned.

Workers have the opportunity to take advantage of the labour shortage and organise to demand better terms and conditions.

The bosses and their government intend to make us pay for their crisis, just as they did following the 2008 financial crash. They hope that the threat of rising unemployment when the furlough ends at the end of September will scare workers into accepting whatever they offer us.

Planning

However, the pandemic has exposed just how necessary our labour is to the continued functioning of the system, and that it is workers who produce wealth in our society. At the same time, it has revealed that ‘just-in-time’ exists to maximise profits for employers.

Furthermore, the climate emergency poses the question of a massive shift away from carbon-based road transport to rail freight. Only an economy planned on a socialist basis—for the social good, not private profit—can achieve this in the necessary timescale. We need democratic planning of the economy, with public ownership of manufacturing, transport and distribution, energy and public services.

Build fighting unions

The starting point in this struggle is a widespread campaign to recruit workers in the logistics industry into the trade unions, and to overcome the fragmentation of the union movement through the fight for industrial unions covering each sector.

The trade union bureaucracies’ historic neglect of widespread areas of the economy employing millions of mainly young and migrant workers and their increasing willingness to surrender terms and conditions in the face of ‘fire and rehire’ threats demonstrate the need to revolutionise the labour movement.

Militants need to organise around a rank and file programme to overthrow the existing trade union bureaucracies. Union officials must be subject to regular elections and immediate recall, and should be paid an average skilled worker’s salary.

Workers must organise to force their union leaderships into calling for an indefinite strike in the logistics industry to demand: