One hundred years ago Ireland fought a war of independence against British imperialist occupation. The revolutionary period opened up by the Easter Rising in 1916 was to boil over into a guerilla war against British forces. In the wake of the First World War, Lenin’s ‘imperialist epoch’ had indeed been borne out as an epoch of wars, revolutions and national revolts and Ireland became one of many national revolts across the world that sought to throw off the imperial yoke.

The aftermath of the defeated Easter Rising saw the British government execute 16 leaders of the rebellion including the socialist James Connolly, wounded and strapped to a chair. This undoubtedly enraged Irish society outside of the strong Unionist areas in the north east. Equally important was the impact of the World War as thousands of Irish in the British Army had been slaughtered and a widespread fear of conscription gripped Ireland.

Set against the backdrop of a politically and economically downtrodden people Ireland’s radicalisation deepened. This was clearly shown in the April 1918 General Strike that defeated Britain’s attempt to introduce conscription. The victory led to a huge spike in recruitment to the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union and a rash of strikes.

Dail Eireann established

As the winds of rebellion gathered, the first casualty was the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) of John Redmond. The ‘Home Rule’ party denounced the Easter rebels. They had unashamedly recruited to the British Army, having been sold the promise of Home Rule after the war. Home rule was a form of limited self rule within the Empire not independence. The General Election of 1918 saw them wiped out as Sinn Fein, calling for an independent republic, won 73 seats, 22 to the Unionists, and 6 to the IPP.

Sinn Fein used its democratic mandate and established the first Irish Parliament, Dail Eireann, in 1919. Britain refused to recognise the Dail and declared it a dangerous association that must be suppressed. The Dail then met in secret and sought to administer the country and organised its own courts. This involved boycotting the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and the existing Volunteers became the Irish Republican Army, the new guardians of the Dial.

Throughout this period Britain continued its militarisation of Ireland. The country was awash with troops, 43,000 in 1919. Alongside the RIC they suppressed all Dail activities, with raids and arrests a constant feature of life throughout the island. Markets and fairs were often dispersed, as were classes in the Gaelic language and games organised by the Gaelic Athletic Association. Indiscriminate summary executions were common and jail sentences were dished out for persons with republican literature, for ‘seditious’ speeches and even for singing rebel songs.

Local elections in 1920 showed once more the strength of Sinn Fein support. Irish Republicans including IRA officers were elected as councillors and Lord Mayors, with eleven out of twelve cities and boroughs declaring for the Republic with the exception of Belfast. Tomás Mac Curtain IRA Commandant, had been elected as Lord Mayor of Cork. After the shooting of a policeman in Cork, Tomás was murdered in his own home as a reprisal by the RIC. His place was taken by Terence MacSwiney who was eventually arrested at a meeting in the City Hall, transported to Brixton prison where he ultimately died after a 74 day hunger strike.

Raids and reprisals

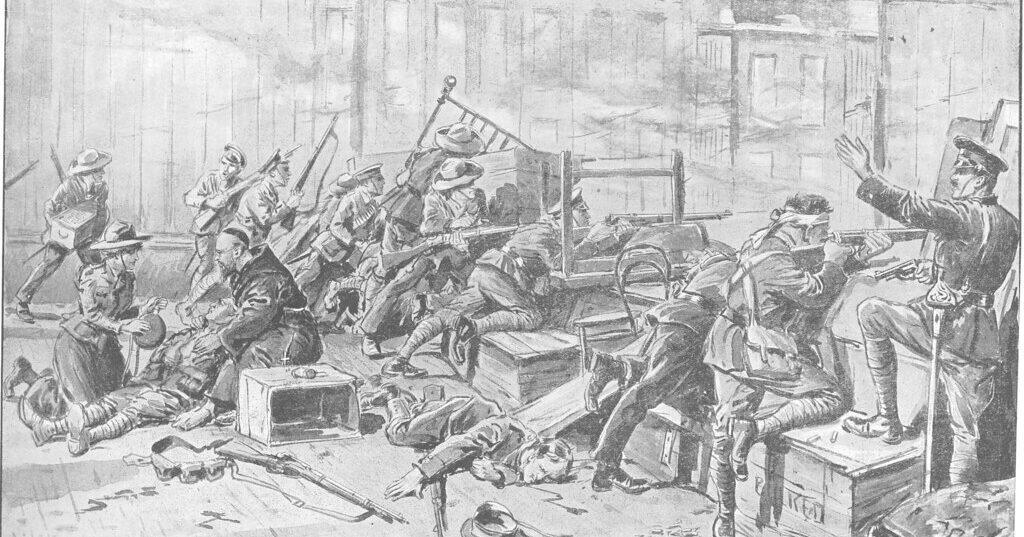

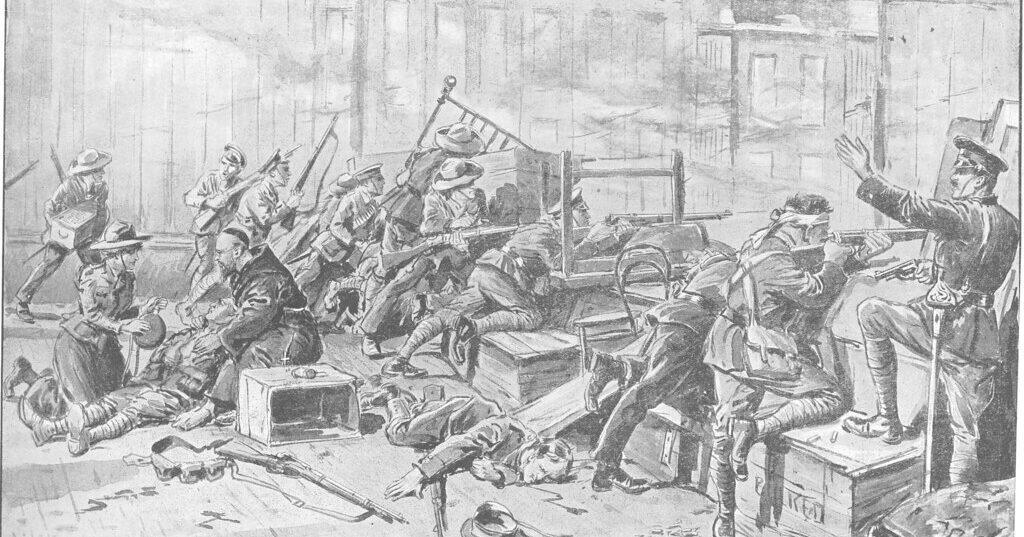

The War of Independence which raged between 1919 and 1921 witnessed the birth of modern guerrilla warfare. The IRA was organised in Flying Columns and ambushes were carried out on police and soldiers. The most famous of these was the ambush at Kilmichael in Cork where Tom Barry’s flying column killed 18 Auxiliaries.

British forces included the RIC, which had been driven out of nearly all of their burnt out rural police stations, the Auxiliary division of the RIC, made up of demobilised British army officers, the notorious Black and Tans, recruited as constables from Britain’s unemployed former soldiers, the Ulster Special Constabulary, an exclusively Protestant armed force from the north and regular British army units. Winston Churchill was responsible for the British garrison in Ireland and the pretense that police forces were capable of dealing with the ‘murder gangs’, in reality a militarised police force stuffed with British ex-soldiers

The pattern of British reprisals that emerged was showcased in 1919 in Fermoy where the killing of a soldier was punished by 200 British soldiers sacking and looting the town. This became an endemic feature of British policy as many urban areas suffered the same fate, like the sacking of the small town of Balbriggan where two young men were bayoneted to death. A new low was struck when much of Cork city’s centre was burnt down by Auxiliaries and Black and Tans in late 1920.

British repression was unrelenting. Martial law was declared in many Irish counties. During the month of October 1920 alone, 17 Irish people were murdered by secret service agents. Michael Collins as Director of Intelligence for the IRA organised a wipeout of 14 such agents in Dublin. Within hours the Auxiliaries had taken their revenge by shooting indiscriminately into a Gaelic football crowd at Croke Park; this Bloody Sunday massacre left 14 dead and 60 injured.

In 1921 the Labour Party issued a report in response to British army atrocities in Ireland stating that things were being done ‘in the name of Britain which must make her name stink in the nostrils of the whole world’, condemning ‘the reign of terror in Ireland’ and how this might be at odds with ‘an empire that is a friend of small nations’. A welcome voice of protest from Labour but within the context of its general policy of support for the Empire, hardly a friend of small nations! Labour could not bring itself to endorse an Irish Republic and went on to support the Treaty.

The Anglo-Irish treaty

Before any negotiations took place, the British had introduced The Better Government Act in 1920 which sought to give Home Rule to the north and south, effectively partitioning Ireland. Elections were held in June 1921 for both the six counties and 26 counties, the former established a Unionist majority in a northern Parliament whereas the southern election saw 124 out of 128 elected unopposed as Sinn Fein representatives who immediately convened a second Dail reaffirming the Republic and rejecting Home Rule. So no joy here for the British.

By 1921 the war was at an impasse. The IRA did not have the military capacity to drive out the British, but they enjoyed majority support from the people. Britain was unequivocal in its rejection of separation, demanding allegiance to the Crown. Britain did not want a costly war but threatened a complete suppression of Ireland if resistance continued.

By the end of 1921 negotiations and a truce had begun between Lloyd George’s government and Eamon De Valera’s Sinn Fein. Truce was followed by a treaty as Griffiths and Collins signed up to a sell-out deal which was rejected by De Valera, now President of the Dail. The Dail voted narrowly in favour. De Valera resigned. The terms of the Treaty saw Ireland partitioned into a northern Unionist state of six counties with a significant 33 per cent Catholic/nationalist minority and a southern Irish Free State of 26 counties.

Both states remained within the Empire with the north still part of the United Kingdom and Britain retaining a military presence in Irish ports in the south. The southern Parliament had dominion status and still had to swear an oath of allegiance to the Crown. A boundary Commission was also included to give the illusion to Sinn Fein that more border nationalist areas might be moved ‘south’. Nothing came of this false hope.

The Treaty was bitterly contested in the south with the IRA split down the middle. A civil war ensued in which the British armed the Free State forces that eventually defeated the anti-Treaty IRA. Business employers, large landholders and the Catholic Church swung behind the Free State and backed a brutal repression of republicans and militant trade unionists. The ‘carnival of reaction’ that Connolly predicted with the arrival of partition was now realised.

Reaction reigned supreme not just in the confessional and British backed semi colony of the south but also in the north where ‘Northern Ireland’ became a prison house for Catholics. Throughout the war Catholics had been subject to pogroms which saw thousands driven out of their homes and over 10,000 Catholic workers and a minority of ‘rotten Prods’ (insufficiently loyal) expelled physically from their shipyard jobs. A vicious sectarian state with discrimination and gerrymandering rife was in the making which would face the wrath of Catholics many years later. By 1923 the counter-revolution had been completed. The Irish war of independence had been defeated.

Working class action

Nationalist narratives of this period have rarely gone beyond seeing this conflict as one of inspiring individuals and a heroic IRA guerilla war. There has been little attempt to understand the revolutionary dynamic of the period with mass action from workers deliberately ‘locked out’ of Irish history. Yet after 1916 the Irish working class entered the fray with a militancy which recalled the prewar rise of syndicalism and in particular the heroic five month Dublin Lockout in 1913.

The major flashpoints of workers’ action were:

The mobilisations of workers in this period showed quite clearly the potential of the working class in taking over the leadership of the national struggle and away from Sinn Fein. The use of the general strike weapon and the readiness to use arms were there for all to see. A decisive lead by the working class, bringing in its wake the rural labourers and small farmers, could have built soviets on a permanent and national basis defended by a workers’ militia on the road to a Workers’ Republic. This is the essence of the strategy of the Permanent Revolution which had just recently been successfully applied in Russia where a democratic revolution had transitioned into a proletarian revolution led by the Bolsheviks.

In this way the IRA’s armed actions could have been part of and subordinated to the interests of a mass and armed rebellion rather than the unlikely victory of a purely guerrillaist strategy of defeating Britain. The absence of any democratic councils of action with control over the course of the struggle also allowed Sinn Fein leaders to sell out with impunity. There was no Bolshevik type party with a clear programme of social and economic demands linked to the struggle for national independence.

The Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Congress that Connolly had helped to found should have been the party leading and organising workers against British Imperialism and capitalism. Instead it agreed not to challenge Sinn Fein in the 1918 elections, agreeing that ‘labour must wait’ until a Republic is first established and not arguing for an independent class programme. It could not even bring itself to defend the Rising or condemn the executions of its founder Connolly. Irish Labour went on to become a loyal opposition in the Free State parliament which followed the defeat of the Republicans in the Civil War.

Despite the contribution of the working class to the independence struggle, Sinn Fein undermined any forward march of labour. It was hostile to strikes and occupations and small farmer takeovers of landed estates in the West. It was of course led by a mixture of bourgeois and petit bourgeois pro-capitalist politicians, the most conservative of which readily went along with the Treaty. The class contradictions within the movement were blown apart when the Treaty was signed and the Irish bourgeoisie was hoisted to power in the south on a deal which was far removed from a Republic. A revolutionary crisis ended in counter revolutionary regimes north and south of the border. It could have been different. If heroism and martyrs was sufficient for success, then Ireland might have been free of Britain long time ago. A successful struggle against imperialism would have required a mobilised and politically independent working class, with small farmer and rural labourer support, that was not going to stop at the stage of ‘national freedom’, that was not going to rely on the hesitant middle class nationalists, but was willing to move forward to the socialist tasks in building a Workers’ Republic.