EDUCATION SECRETARY Nadhim Zahawi recently told teachers that ‘empire and imperialism… should be taught in a balanced manner’. Historical figures ‘who have controversial and contested legacies’ should be portrayed using only the ‘most renowned and factual information about them’.

The Tories are desperate to put a positive spin on the teaching of the British Empire due to their definition of ‘British values’ as: Democracy, Rule of Law, Respect, Tolerance and Individual Liberty. They want to airbrush out everything in its history that does not square with this: the record of slavery, the wars of conquest in Asia and Africa and the repression of the independence movements.

They want to replace, or at least ‘balance’ this history of oppression with tales of the benefits of British rule, ‘modern’ education, railways and finally the ‘gift’ of independence itself when colonial peoples proved themselves sufficiently ‘civilised’. They add to this the loyal service and sacrifices of colonial troops in the two World Wars, all resulting in the benevolent British Commonwealth, headed by our ever-smiling Queen.

This picture of the British as the good imperialists, compared with the bad ones like the Belgians (King Leopold’s Congo) or the Germans in Africa and later in Eastern Europe, still does service in suggesting that Britain’s participation in the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq and today its militarisation of Eastern Europe and the South China Sea have similarly benign purposes.

Empire is the pivot around which British national identity revolves; to question the positive narrative of Britain’s empire might lead people to challenge Britain’s current imperialist policies.

What was the empire?

The British Empire was always a capitalist endeavour. The original colonists in North America were largely subsidence farmers and merchants who traded mostly with the indigenous American inhabitants, but they soon became eager to seize their land and drive off or murder the ‘savages’ who, unaccountably, resisted this.

The rapid growth of slavery and the slave trade in the 17th & 18th centuries put an end to this early phase. Not only did it promote the rise of giant plantations and the acquisition of the labour force to work them, it also accumulated a huge sum of capital that would eventually power the industrial revolution.

This phase is often referred to as the First British Empire. It involved the genocide of the indigenous peoples and the capture, transportation and enslaving of millions of Africans and Asians. A huge proportion of these were murdered or infected with fatal diseases in the process. It also entailed wholesale theft of the property of those that remained “free”.

From the second half of the 1700s, the Second British Empire began to take shape. The loss of the American colonies was more than compensated for by the conquest of India, southern Africa and Australia. Colonial governments were installed and, more importantly, the empire was turned into a gigantic, global money-making machine.

Britain’s industrial revolution was fuelled by the first phase of empire, a process Karl Marx called the ‘primitive’ or original accumulation of capital. This vastly increased Britain’s productivity and output, as well as its hunger for ever more raw materials. The home market was quickly outgrown and gave way to the world market.

Profit was to be made at each turn of the circuit of capital. Once Britain had sufficient control of its colonies, it could abolish the slave trade in 1807 and slavery itself 27 years later. In part this was because it feared uprisings of the slaves, such as that which took place in Haiti and in its own Caribbean colonies, but also because it could increasingly rely on the wage labour of the newly colonised peoples: just as cheap and in fact more adaptable than slave labour. By controlling all imports into the colonies, the British could sell its goods abroad without competition from its European rivals.

To show how British imperial policy conducted the milking of this global cash cow, it is instructive to look at the abolition of slavery. In the same year that this was achieved, 1834, the British ruled that Caribbean planters could purchase cheap land in India, so they could carry on their production of raw materials with Indian labour.

Those plantation owners that stayed in the Caribbean, on the other hand, needed labour to replace the newly liberated slaves, who were now unwilling to work on the estates. The British duly implemented the ‘coolie’ system, transporting indentured Indians, cheated by lies about their future rights and pay, who replaced African slaves and could be driven by the same brutal whips.

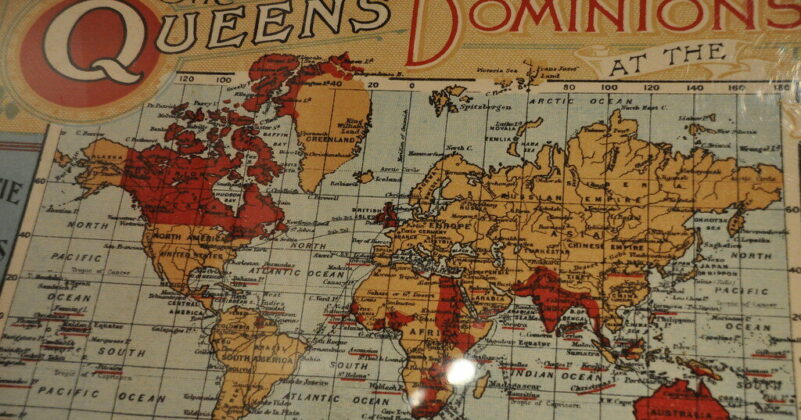

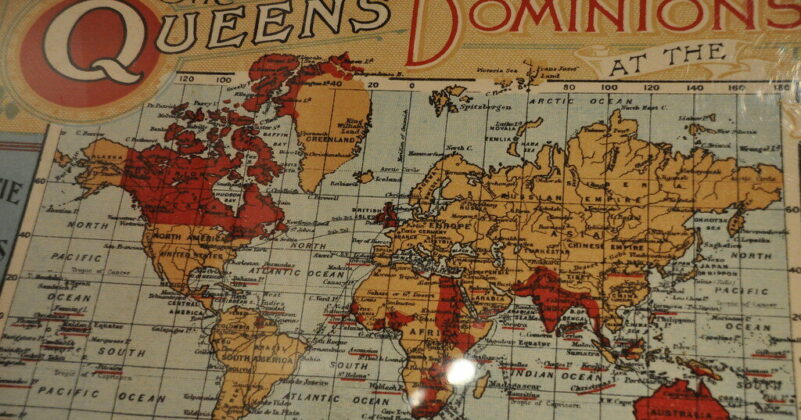

By 1922, a quarter of the world’s population, 458 million people, lived under British rule. They in turn produced up to 37% of the world’s GDP (1913), while occupying a quarter of its land mass. This was the height of the empire, but not the end of Britain’s global exploitation.

India – the jewel in the crown

The East India Company was formed in 1600 and grew over the next 250 years until it effectively ruled large swathes of modern-day India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Starting on the west coast around Bombay (Mumbai), the company, which had its own army, won exclusive trading rights, then land-owning and taxation rights. It gobbled up the eastern shore from Madras in the south to Calcutta (Kolkata) in Bengal and finally drove inland through Lucknow and Delhi to the Punjab.

The turning point came at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, where Robert Clive (whose statue still towers over Whitehall) defeated the Nawab (ruler) of Bengal. Thereafter Clive boasted there would be ‘little or no difficulty in obtaining the absolute possessions of these rich kingdoms’. He certainly took personal possessions during the conquest, finally leaving India £250,000 richer. It was in this period that the Hindi word ‘loot’ came into the English language. It has been estimated that Britain looted nearly $45 trillion (in today’s money) from India between 1765 and 1938.

The British imposed high taxes on the colonial population, which they used variously to pay for the building of India’s railways (supposedly one of our ‘gifts’ to the subcontinent), a huge army of 250,000 soldiers, the vast majority of them Indian, and to buy India’s cash crops for export back to Britain, which could then be worked up into finished products and sold back to the Indians. Despite Indian textiles being of superior quality, their products were taxed to the hilt and their export forbidden; manufacturers were soon driven out of business.

India became synonymous with cheap labour at home and abroad, which to some extent it still is. Agricultural wages in Madras were as little as £1 a month and industrial wages only slightly higher. Between 1833 (the abolition of slavery) and 1938 around 30 million Indians were exported as indentured labourers, whose plight – torture, rape, working to death – was little better than that of the African slaves they replaced.

Indian farmers were forced to produce cash crops, like cotton and indigo, replacing staples, like wheat and rice. And the latter were collected in taxation even when the harvest failed in drought years. The result was famine and starvation, which killed up to 29 million people. The most infamous of these great famines came in 1943, when 4.3 million Bengalis starved to death.

Indian mutiny

Ironically it was the Indian soldiers, raised and trained by the East India Company, that nearly undid the empire completely in 1857. The soldiers, called sepoys, were terribly treated and subject to racism, as was the population as a whole. They were concentrated, Hindu and Muslim alike, in a disciplined mass force spread across the country.

When 90 sepoys stationed near Calcutta were told to bite the paper wrapped around cartridges that had been greased in beef and pork fat (objectionable to both faiths), they rebelled, shooting their officers and setting out to march on Delhi, where they hoped to kill their British masters and re-install the Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah II on his throne. The rebels gathered in numbers along the way and held Delhi for 10 weeks before it was brutally ransacked by the British.

As the rebellion spread through town and country, the insurgents killed up to 40,000 British officers and civilians. The unity between Muslims and Hindus struck fear into the British, with Disraeli saying in Parliament that this was ‘more than a mutiny… a national revolt’. Eventually, nearly two years later, British soldiers diverted from China and other parts of the empire finally put down the revolt at the cost of 800,000 Indian lives.

From empire to imperialism

Britain was the dominant global power throughout the 19th century. However other European powers, France, Germany, Belgium, Holland and others, eventually caught up industrially. This resulted in the ‘Scramble for Africa’, most of which was not formally colonised, beyond its coasts. In just over a decade the rival European powers divided up the giant continent, justifying massive land seizures by ‘effective occupation’ (Treaty of Berlin 1884).

This began a transition from free trade capitalism and colonialism to what Lenin called the epoch of imperialism. Britain remained first among a handful of robber nations, including France, Germany and later the USA, dividing the world. The First World War saw the lesser imperialisms – Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire – try to despoil Britain of some of its plunder and their defeat resulted in the British seizure of German colonies and a large part of the Ottoman Empire. In contrast, the Second World War saw Britain massively in debt to the USA and obliged to disgorge her huge empire in the 20 years after 1945.

Whatever Tory ministers decide, teachers and students must fight to ensure that the true history of the British Empire is taught in British schools. This must include its ‘subject’ peoples’ struggle for freedom. An incomplete list of them from the twentieth century alone includes: Ireland’s armed struggle for independence; Gandhi and the Indian National Congress mass civil disobedience campaigns; the Indian naval mutiny of 1946; the general strikes in the Caribbean islands and ‘British’ Guiana; and the post-war Kenyan and Malayan liberation struggles.

It must include too the British response – brutal repression, including concentration camps – and those colonies where the British left white settlers minorities in control: Palestine, South Africa and Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). Given British schools have so many students whose families come from former British colonies, it is an insult to them and a disservice to their ‘indigenous’ British comrades to try to censor this.

The real legacy of empire

Today Britain’s role on the world’s stage has become no less duplicitous or rapacious than in days of old. Hitched to the world’s most powerful imperialism, the US, Britain is taking a full and prominent role in the new Cold War against Russia and China, hoping to aggrandise and stabilise its world rule, albeit as a subordinate partner.

In this relationship, Britain offers its accumulated experience in running an empire, politically, economically but most of all militarily. Indeed it still claims property rights on islands scattered across the globe where it has bases. One such example is the Chagos Islands, leased to the Americans, which it refuses to hand back to its people who they deported en masse in the 1960s.

But exposure is only the first step. It must lead to action: solidarity with all anti-imperialist struggles and resistance to militarisation, sanctions, and the renewed drive to war: the main enemy is and always has been at home.

The real positive legacy of Empire are the communities in Britain who are ‘here because we were there’ – from the Caribbean, Africa, the Indian subcontinent and the Middle and Far East. They have enormously enriched the culture and increased the fighting strength of the British working class.