By Tobi Hansen

The Role of the USPD

The USPD was a centrist organisation that oscillated between reform and revolution, between radical struggle and adaptation to the SPD and, through it, counterrevolution. While the leadership of the SPD wanted by all means to strangle the socialist revolution at birth and for this purpose entered into close collaboration with the state functionaries, the big industrialists and the army high command, the leadership of the USPD wanted half a revolution, so to speak.

Ideologically, this is reflected in the fact that its leaders, like Karl Kautsky, wanted to combine the role of workers’ councils (Räte) with the sovereignty of the National Assembly. The dual power situation between the (potential) organs of power of a new order, the workers’ and soldiers’ councils, and the Constituent Assembly, which served as a focal point and symbol for counterrevolution, was to be perpetuated rather than resolved, one way or the other.

The policies of the USPD were all the more tragic as the sincerely revolutionary leaderships of the party rank and file, while subjectively pushing more and more for revolution in the first months of revolution, did not make the decisive break with their leaders who were looking for a compromise and reunification with the SPD. The Spartacus League did unite with the “International Communists of Germany” (the “Bremen Left Radicals”) and other war opponents to form the “Communist Party of Germany” (KPD). Ultimately, however, this foundation (30 December 1918-1 January 1919) came too late to provide an effective leadership for the revolutionary vanguard at the critical conjuncture that was looming. The party itself was still politically immature, plagued by a sectarian approach to tactics and was unable to win over the left wing of the USPD, which only joined the KPD in 1920.

The centrist policies of the USPD and the weakness of the KPD facilitated the SPD under Ebert and Scheidemann gaining control of the workers’ and soldiers’ councils and implementing its programme of provoking the militant elements into a premature fight and then crushing the proletarian revolution in alliance with the Reichswehr and big business.

Counterrevolutionary Social Democracy

The SPD did not only have a majority in the Councils. Unlike the USPD, it also had a clear, counter-revolutionary programme. Ebert, Scheidemann, Otto Wels, Gustav Noske and other social democratic party leaders played on several levels.

On the one hand, they delayed all progressive decisions, every important measure against reaction. A central means was the constant appeal to the “unity” of the working class and the argument that the “undemocratic radicalism” of the Spartakists and the USPD left would endanger the achievements of the republic and peace. The important decisions, they insisted, must be postponed until the Constituent Assembly met. The councils were only advisory or supplementary bodies to the government and a future parliament, not the organs of a dictatorship of the proletariat.

Finally, the councils, which represented only a “minority” of the population, should not anticipate the much more representative National Assembly, which would represent the entire people. The USPD itself was politically and ideologically incapable of answering this, as it did not understand or acknowledge the counterrevolutionary character of the National Assembly in the first place.

On the other hand, Social Democracy conspired to bring the front line troops, still loyal to their officers, back to Berlin and other urban centres. In this, they were supported by the near monopoly of information of the bourgeois and reactionary as well as the social democratic press. The SPD leadership resolutely defended the existing state bureaucracy, police and military apparatus against the inroads of the Räte. Indeed they supported the formation of fresh counterrevolutionary forces, the Freikorps. This policy naturally included provocations against the left, the workers’ councils and the sailors of the People’s Marine Division, who came to protect the revolution in Berlin.

At the same time, the left, including the elected representatives, failed to prepare the workers politically and organisationally for the confrontation. For example, many workers were armed, but a workers’ militia or red guard was not established. Although the USPD protested against several measures and manoeuvres of the SPD, it was not prepared to break the “unity” of the councils. Thus it legitimised the policies of Ebert and Noske on the one hand, and disoriented its own followers and discredited itself on the other.

The Spartakist Uprising

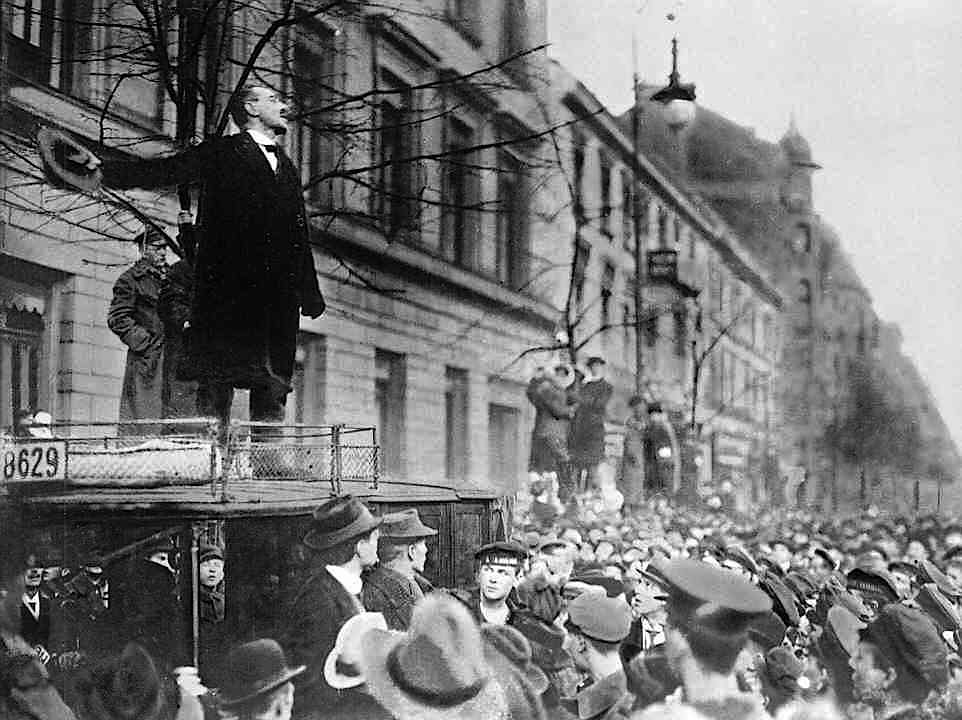

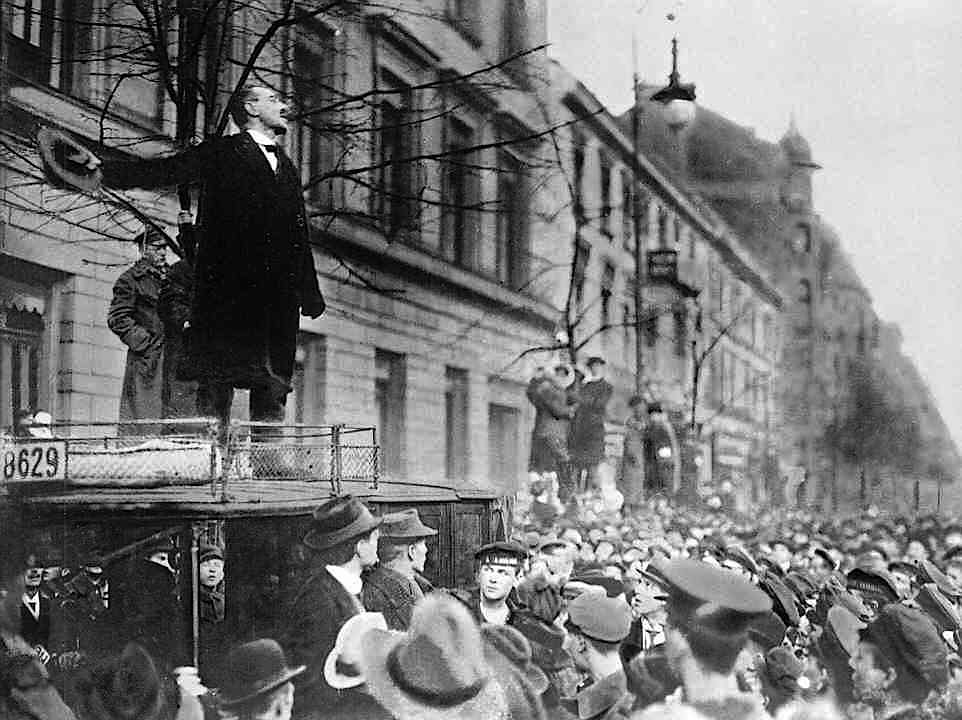

Soon the SPD, and the military allied with them, consciously sought confrontation with the Berlin vanguard of the working class. The dismissal of the USPD police president, Emil Eichhorn, at the turn of the year 1918/19 was intended to force a demonstration of power. When he refused to give up his post, a general strike engulfed the city and a crowd of 150,000 gathered outside the police building. The Spartakists, the Revolutionary Stewards and the USPD of Berlin immediately formed a Revolutionary Committee to meet the challenge.

But the balance of forces was unfavourable to the Spartakists. It was one thing to pack the streets with protesters at Eichorm’s dismissal, quite another to find forces sufficient to overthrow Ebert, Scheidemann, Wels and the entire government, especially with the Constituent Assembly due in a matter of days.

The bulk of the city’s troops were confused and not ready to join the side of the revolution. Under Noske’s leadership, there were now sufficient battle hardened, reactionary Freikorps to take on the ill-trained and poorly armed revolutionary workers. Defensive actions were clearly necessary in the face of the SPD-backed attacks from the armed forces. Such actions could have won the support of the troops. But a struggle for power was premature. Yet the Revolutionary Committee decided to go on the offensive and launch a rising.

On January 7, key buildings such as telegraph stations and newspaper buildings, including the SPD’s Vorwärts, were occupied. 500,000 workers, many armed, heeded the call for a demonstration that day. But then the Revolutionary Committee hesitated and left the crowd standing in the cold, whilst the USPD leaders entered into futile negotiations with Ebert and Co. As a result, many of the city’s regiments declared themselves neutral in the ensuing conflict. The mass impetus of the previous few days was lost.

In the final battle in the newspaper district, the Spartakists and the workers who supported them fought a heroic battle against the Freikorps, who brought up artillery to shell the occupied Vorwärts building. Isolated, they were overwhelmed.

The so-called “Spartacus Uprising” was in reality not a serious insurrection with sufficient mass support in Berlin, let alone in the country. It did not even have the explicit go-ahead from the KPD leadership and Rosa Luxemburg warned of its almost certain failure. Meanwhile, part of the KPD, especially Liebknecht, allowed themselves to be manoeuvred into what looked like a premature bid for power. Unlike the July Days of 1917, when the Petersburg working class and the Bolsheviks were also drawn into such a premature action, the defeat of the “Spartacist Uprising” had much longer lasting counterrevolutionary effects.

The fact that the German counterrevolution had learned more from the Russian experience than the revolutionaries undoubtedly contributed to this. The reaction had reliable frontline troops thirsting for a reckoning with the “Reds,” worked up by the propaganda against “the Jews” and “Bloody Rosa” by the bourgeois press. Moreover, the SPD and its bureaucratic apparatus turned out to be far more hardened and determined counterrevolutionaries than were the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries in Russia.

The murder of Liebknecht and Luxembourg on 15 January 1919, supervised by Freikorps leader Waldemar Pabst, was politically the responsibility of Gustav Noske. Charged with control of the “loyal” military forces in Berlin by Ebert, he infamously commented, “Someone will have to be the bloodhound; I won’t shirk the responsibility”. In fact it was a responsibility he enthusiastically fulfilled over the following months in which many more KPD members were murdered, including another of the party’s key leaders, Leo Jogiches. The Social Democracy bears full responsibility for the attempted decapitation of the revolutionary movement.

Alongside the Freikorps’ bloody crushing of the Berlin “uprising”, the same thing happened to the short-lived Räterepubliken (usually called ‘soviet republics’ in English) in Bremen and Munich. The elections to the National Assembly and the appointment of Ebert as Reich Chancellor, saw the counterrevolution consolidated for the time being.

Lessons of Defeat

In reality, however, these defeats only provided the prelude to further struggles for power between the working class and German imperialism. Learning from the lessons of defeat, the KPD was able to achieve unity with the left wing majority of the USPD. Its leadership, however, still made mistakes or lost opportunities, such as during the general strike that defeated the right wing Kapp Putsch in 1920 and then the missed revolutionary situation in 1923. Between these events, the KPD engaged in another premature attempt at a rising in March 1921.

Indeed, the 1928-33 period, which saw the rise of National Socialism and finally the establishment of the fascist dictatorship, presented further opportunities for revolution had the correct tactics, in particular the united front against the Nazis, been effectively utilised. Alas, the KPD failed in this as well. By then, however, the reasons for defeat lay not with a young and inexperienced German leadership but fully with the leadership of Joseph Stalin and the bureaucratised Communist International.

Hitler’s triumph, in which the Social Democrats once more played a counterrevolutionary role, was the final conclusion of the period that opened so hopefully with the November Revolution. These events all showed that if the working class is not able to win over the decisive forces of the working class in the workplaces and the barracks and to bring a revolution to a victorious conclusion, then the forces of reaction will wreak a bloody revenge on them.

The defeat of January 1919, the deaths of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, might seem to confirm the social-democratic and liberal commentators who present their proletarian-revolutionary, and socialist impulses and goals as the utopia of a hopeless minority. This is not true. Here we remember words from Rosa’s last article for Röte Fahn (Red Flag), which appeared on the day of her murder.

“The whole road of socialism, so far as revolutionary struggles are concerned, is paved with nothing but thunderous defeats. Yet, at the same time, history marches inexorably, step by step, toward final victory! Where would we be today without those “defeats,” from which we draw historical experience, understanding, power and idealism? Today, as we advance into the final battle of the proletarian class war, we stand on the foundation of those very defeats; and we cannot do without any of them, because each one contributes to our strength and understanding.”