By Joe Crathorne

After dismal treatment by university bosses and government ministers, students at 55 UK universities are now on rent strike. Starting in Bristol and Manchester, this wave of rent strikes is now the biggest tenant action since 1973—and it shows no signs of slowing down.

Student rent strikes first appeared in the headlines last November, when management at the University of Manchester erected metal feces around university accommodation.

Within hours, around 800 students had united to tear them down, in a demonstration of the fury felt by students across the country. This resulted in a three-week-long rent strike and campaign of direct action, and the University eventually refunded students’ accomodation costs.

Four months on from the start of the Manchester protests, rent strikes have now been organised at more than a third of all UK universities. While some strikers seem to have been bought off with offers of partial reimbursements and early contract releases, the majority of rent strikes have seen a steady rise in sign-ups.

Student rent strikes are now so popular that even the National Union of Students (NUS)—whose disgraceful betrayal during the 2010 tuition fee rebellion all militant students should remember—have sought to organise the strikes on a national basis through its Students Deserve Better campaign.

The experience of this current generation of undergraduates during the pandemic has exposed the marketisation of higher education. Universities are now businesses, and students have become cash cows.

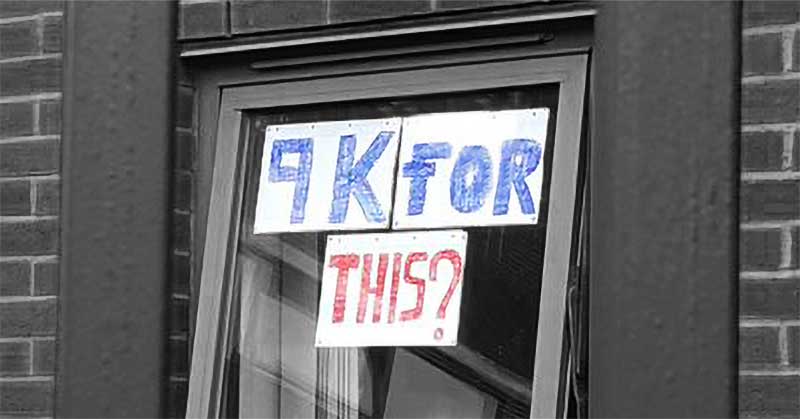

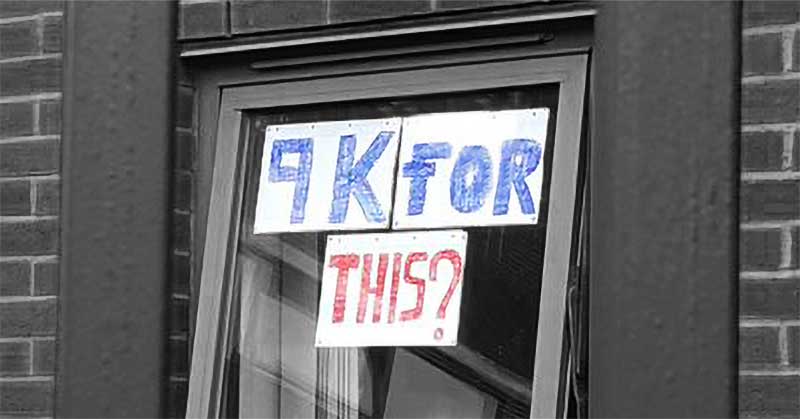

First-years have been forced to pay extortionate rent and tuition fees for substandard education and often quarantined accommodation, while universities’ promises of a blend of in-person and online teaching has not materialised.

As well as sky-high rents, new sign-ups to rent strikes cite among their reasons for getting involved: living restrictions; heavy-handed security; and a systematic failure to address reports of sexual abuse, such as in University of London (UoL) intercollegiate halls, where months-old reports have gone unanswered.

The massive wave of rent strikes is a testament to the ability of student organisers to use collective action to fight for their demands. The task for revolutionary socialist students is to argue for increased organisation, militancy and coordination of the rent strikes.

In order to win their struggle, militant students will need to be determined and organised, and develop techniques to raise the awareness of their comrades and incite them to direct action.

Rent strikers must refuse offers from management intended to divide the strike. Just as importantly, they must reject the reformist leadership of the NUS, and retain the independence necessary to form militant student organisations on the back of the strikes.

University workers are already campaigning against the unmanageable workloads imposed upon them by the for-profit higher education system. Union branches across the country are considering industrial action, and these actions should be generalised across the sector and linked up with the student strikes in a struggle for a free, nationalised higher education service under the control of workers and students.

Tuition fee strikes at SOAS and Goldsmiths, University of London, show one potential avenue for escalation. With the easing of coronavirus restrictions, new possibilities will open up for a student movement with revolutionary socialist politics—reinvigorated by the widespread success of the rent strikes!