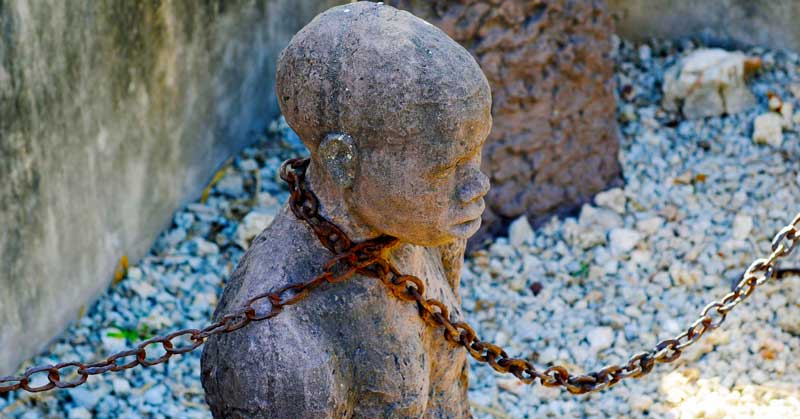

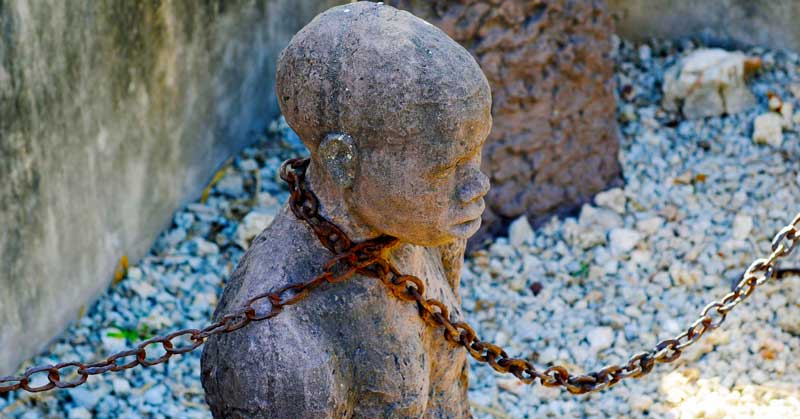

Photo Credit: Flickr

This year the movement which was unleashed by the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd in the United States and reverberated around the world, has brought racism directed against black people to the fore in a way not witnessed since the 1960s and the 1980s. The link between todays’ police killings and the historic roots of this oppression was made when the statue of Edward Colston (1636-1721), slave trader and “philanthropist”, was pulled down on 7 June and thrown into Bristol harbour, where his ships had docked after the infamous triangular run.

Black History Month –with its objective of drawing attention to the exclusion of black and mixed race people from the “national narrative” – takes on a particular importance this year. Since its London launch in 1987 it has sought to show that the transatlantic slave trade – which British ship owners, merchants and plantation owners dominated for over century – was an essential element in the development of this country’s capitalism and therefore an integral part of “our history”. It was – and still is – necessary because Conservatives and right-wingers of all stripes have tried to make British history a white history. The National Front fascists used to chant “there ain’t no black in the Union Jack!”

The historian David Olusoga – whose family was driven from their home by NF thugs when he was fourteen – has shown in books like Black and British A Forgotten History and BBC2’s Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners, how many of the great eighteenth century monumental mansions, like Harewood House, were paid for out of the stupendous profits made from the slave trade and sugar plantations in Barbados, Jamaica and Demerara (Guiana). Likewise the civic splendour of Liverpool, London and Bristol was, in large part, paid for by merchants and bankers whose wealth came from these sources.

Slavery

Of course for years children and students were taught slavery existed but the story was mainly about how the saintly MP William Wilberforce battled for abolition and how the Royal Navy suppressed the slave trade. The slave revolts in Jamaica and other Caribbean islands, the victorious Haitian Revolution – i.e. the agency of slaves in their own freedom – was not mentioned. It was the combination of fear of an imminent slave uprising and the after effects of the mass popular movement that led to the 1832 reformed parliament that secured the passage of the abolition act on 28 August 1833.

The fortunes made out of chattel slavery for over two centuries long received only most cursory recognition, as did the fact that from the later seventeenth century England/Britain was the main perpetrator of this monstrous crime.

But since the 1970s and 1980s a whole series of books have started to tell and analyse this story. They have shown how the capital accumulated from the forced labour of Africans, torn from their homelands, was invested in banking, factories, railways and colonies. Worse still, in 1833, 46,000 slave-owners were paid a very generous compensation by Parliament of £20 million, around £17 billion in today’s money, for their human chattels, a bill finally paid off by taxpayers in 2015. Meanwhile the “freed” slaves received no compensation whatsoever and certainly no land; they even had to work for 40 hours a week – unpaid – for their masters for a further five years.

In fact Karl Marx explained the importance of slavery to the genesis of capitalism as early as 1847 in his early work The Poverty of Philosophy:

“Direct slavery is just as much the pivot of bourgeois industry as machinery, credits, etc. Without slavery you have no cotton; without cotton you have no modern industry. It is slavery that has given the colonies their value; it is the colonies that have created world trade, and it is world trade that is the pre-condition of large-scale industry. Thus slavery is an economic category of the greatest importance.”

Whilst he recognized that slavery had existed in classical antiquity, in the Islamic world and indeed in the patriarchal systems of West Africa itself, this lacked the cruel intensity of exploitation seen on the plantations. He observed in a draft for Capital, that it reaches “its most hateful form … in a situation of capitalist production,” where “exchange value becomes the determining element of production.” This leads to the extension of the workday beyond natural limits for its reproduction, literally working to death the enslaved, male and female.

Marx also insisted that if the movement of the modern proletariat, i.e. the “ wage slaves,” did not fight for the liberation of the chattel slaves then they would never be able to end their own exploitation.

“In the United States of North America, every independent movement of the workers was paralysed so long as slavery disfigured a part of the Republic. Labour cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded.”

This same principle applies today to the descendants of the victims of slavery and colonialism who still suffer racism.

Racism as Ideology

The findings of many scholars confirm that racism based on skin colour was largely a product of the African slave trade and the need of the slave owners to justify treatment so at variance with the written teachings of the founder of their religion and modern Enlightenment principles. To do this they developed racism.

The use of the term race came to designate whole groups supposedly superior and inferior to one another, the suitability of some to intellectual pursuits and to be masters, of others to be restricted to hard physical labour. This was and is an artificial political and social construct. All indigenous peoples with darker skins than Europeans were designated in Rudyard Kipling’s infamous words as “half devil and half child” (The White Man’s Burden). They had, it was claimed, an innate incapacity for civilization. Racism thus “justified” both African enslavement and the mass extermination of indigenous peoples in the Americas and Australasia.

The “white race” too was as much a construct as the “black race” and was promoted by the colonialists in North America as a conscious means to stop the many poor European indentured labourers from uniting with people of African origin against their exploiters.

As religion declined as an effective ideology, a “scientific” discourse emerged based on odds and ends stolen from anthropology, animal breeding, plus complete pseudo-sciences like phrenology, eugenics, etc. But modern racism has shown itself capable of endless transmutations. After its “discrediting” by the Nazis, recent attempts centre on the supposed incompatibility of certain civilizations or cultures.

But before we kid ourselves that this year’s talk of “inclusivity” in the national narrative is permanent and that black history will be henceforth a part of British history, we should remind ourselves that these sort of proposals have been made time and again. Twenty-one years ago the Macpherson Report into the racist killing of Stephen Lawrence, as well as condemning the Metropolitan Police for institutional racism, also demanded that “consideration be given to amendment of the national curriculum aimed at valuing cultural diversity and preventing racism, in order better to reflect the needs of a diverse society”. We’re still waiting.

In March this year the Windrush Lessons Learned review by Wendy Williams (see gov.uk), like Macpherson, observed, “the Windrush scandal was in part able to happen because of the public’s and officials’ poor understanding of Britain’s colonial history, the history of inward and outward migration, and the history of black Britons”.

The real test however is how that history is dealt with practically today. And the Windrush scandal itself should be a warning. In 2018 it transpired that some 50,000 people who had come to Britain before 1973, many as small children with their parents, were being targeted for deportation. Despite working their whole lives in Britain’s factories, hospitals and public services, despite having children and grandchildren born in Britain, at least 83 were actually deported.

This shameful episode was part of a conscious policy named after then Home Secretary Theresa May’s pledge to “create a really hostile environment for illegal migrants”. Vans were driven around areas with large black, Asian and immigrant communities: “In the UK Illegally? Go Home of Face Arrest” emblazoned on them.

Of course apologies have been made but now we have yet another Tory Home Secretary, Priti Patel, who promises the biggest overhaul in the asylum system for decades that will “immediately return” those who have “no claim for protection”, i.e. before refugees can access lawyers to present their case. It seems Patel has since asked Home Office officials to consider imprisoning asylum seekers on disused ferries moored off the south coast and even deporting them to Ascension island, a speck of rock jutting out of the Atlantic ocean, 4,000 miles away.

For a state that for hundreds of years sent millions of its citizens to North America, Australia, Southern and West Africa, this obsession with preventing people coming here is outrageous hypocrisy.

Empire and Colonialism

Important as slavery is as the historic root of anti-black racism and “white supremacy”, a closer look needs to be made into the history of the British Empire. Black History Month has not been so successful in bringing to light the crimes committed during the era of colonialism and imperialism, which expanded worldwide after slavery’s abolition. Indeed to some extent – as far as the seizure of territories in Africa was concerned – Britain colonised large swathes of the continent, hypocritically donning the “halo” of anti-slavery: bringing “civilization” and Christianity to a “benighted” people.

When it comes to this history, there is much more resistance to its “inclusion” in the national curriculum. Those who try are accused of wanting to teach children to hate their own country. Conservatives are hypersensitive to any raising of the subject, especially in the teaching of young people. This is because the spoils of Empire, its exploited labour forces, its African and Indian regiments sent to fight Britain’s wars, its raw materials and markets formed the material foundation of the modern British state and nationality. They were the base too of the “pomp and circumstance” surrounding the makeover of the monarchy. Since the modern wars of intervention – Afghanistan and Iraq – Labour as well as Tory governments have actually tried to sanitise and re-package the story of Empire.

This history starts with the brutal conquest of Ireland, Britain’s first colony, and the expropriation of the original inhabitants, huge numbers of whom were driven to emigrate. Followed by the north American colonies, whose inhabitants were driven off the Atlantic seaboard into the plains, and largely exterminated. Then came the East India Company’s looting of India and the destruction of its textile industries, the artificial famines in Ireland and India, the brutal conquest of African Asante and Zulu Kingdoms. The atrocities committed by the Indian sepoys in the Indian Mutiny have been retold countless times but the terrible revenge exacted by the British imperialists still remains unacknowledged. Then there was the wholesale robbery of the best lands in West Africa for English farmers and, in the Boer War, the formation of concentration camps not only for Boer civilians, but also Africans.

To this we must add the Opium Wars. Starting in 1842 Britain led the way in carving out extraterritorial concessions in the key ports of China. During the second Opium War of 1860 occurred the complete destruction and looting of the old imperial summer palace in Beijing by 4,000 British troops. Various West African Kingdoms, like Benin and Asante, had their capitals looted and burnt. How else were the museums of London packed with colonial plunder such as the remarkable Benin bronzes?

Labour’s racist record

Last but not least were the atrocities committed by postwar Labour and Tory governments trying to hold on to Britain’s colonies. These included the brutal crushing of a Communist-led guerrilla war in Malaya by Attlee’s Labour government in defence of rubber and tin resources justified by the need to build a prosperous, welfare state… in Britain. The Tory government followed this by crushing the so-called Mau Mau uprising in Kenya, imprisoning thousands in camps, torturing and executing many hundreds more. Britain still refuses to compensate the former colonial victims of torture and the Foreign and Colonial Office admits it destroyed the documentation of these events. (See The Blood Never Dried by John Newsinger, London 2006 and Labour: A Party Fit for Imperialism by Robert Clough London 1992)

And when it came to covering up this record Labour – at least in the persons of all but one of its leaders – has a disgraceful record. Clement Attlee, a hero few on the left criticise, fearing a hostile public reaction to Caribbean immigration, in 1948 actually tried to prevent the Empire Windrush from sailing to Britain, instead suggesting that its 492 passengers (many British ex-servicemen) could be diverted to West Africa to work on groundnut farms. In retirement, as Lord Attlee, he claimed in 1960: “There is only one empire where, without external pressure or weariness at the burden of ruling, the ruling people has voluntarily surrendered its hegemony over subject peoples and has given them their freedom.”

Tony Blair repeated this false claim in 2000, referring to the Empire as “a great achievement”. According to Seumas Milne, only his advisers prevented him from inserting in an election speech in 1997 the words “I am proud of the British Empire.” Gordon Brown too claimed on Newsnight back in 2005, “the days of Britain having to apologise for its colonial history are over. We should move forward. We should celebrate much of our past rather than apologise for it.”

The trade union movement too has to recognise the shameful elements of its own history, when many unions operated an unofficial colour bar in the 1950s and into the 1960s. But in 1963 after a four-month boycott of the Bristol Omnibus Company, which was refusing to employ “coloured” crews, the bosses were force to abandon this discrimination. It was the struggles of black workers themselves, aided by socialist trade unionists, that put a stop to these disgraceful practices and whose pressure eventually led to anti-discrimination legislation being passed by Labour governments. Even this, however, was accompanied by tightening of the immigration laws.

The exception is Jeremy Corbyn, but the response to him is instructive. The Labour Party’s 2019 election manifesto promised to conduct an “audit of the impact of Britain’s colonial legacy” with the goal of understanding “our contribution to the dynamics of violence and insecurity across regions previously under British colonial rule.” There can be little doubt that this was further proof to our rulers that under Corbyn Labour was unfit to hold office. If you can’t be trusted with such past “achievements” how can you be trusted with making new ones?

Labour – now “under new management” as Keir Starmer says – is resorting to patriotism to win back voters in the Red Wall, by daubing it with the red-white-and-blue of the Union Jack.

The struggle for anti-racist education

Indeed the whole history of Britain’s exploitation of the world over three centuries needs to be taught and discussed in schools and universities – not just for one month in twelve but the whole year round – and integrated into all subjects. National curriculums still give little space to the history of black and Asian people in Britain let alone to the origins of these communities in slavery and the colonial plunder of the British Empire. As well as the stories of ordinary working people in industry, transport and the education and health services, an integral part of black history is the story of political activists, nationalist and socialist, who came to Britain and organised their independence movements from here.

The story starts with leaders of the abolitionist movement, like Olaudah Equianao (1745-1797), and a leader of the physical force (revolutionary) wing of Chartism, William Cuffay (1788-1870). The 1930s witnessed the socialist and anticolonial activities of George Padmore, CLR James and Jomo Kenyatta. Nor must we forget the black and Asian activists in the new movements of the 1970s and 1980s, like Michael X, Darcus Howe and Olive Morris.

Of course making this widely known in the schools, universities and the media will be no easy matter. It will be denounced as bringing politics into education. Indeed the Tories, fearful of such a transition to anti-racist education, not least because it poses such a challenge to existing society and institutions, have just proclaimed that there should be no teaching of texts that promote opposition to the capitalist system.

But politics – the politics of imperialism – are already there in abundance. Socialist teachers will have to wage a hard struggle to “tell the truth to power” in the whole education system and they will need the assistance of genuine anti-imperialists in the Labour Party and in the trade unions. Anti-racist education can only truly be vigorous if it exposes the way in which racism and capitalist exploitation are two interlocking chains that bind the working class to its wheels. Together, the youth of today must break them.

In the end the teaching of the crimes of racism, perpetrated by “our” ruling class and its Labour lackeys, will only be preparatory to a common struggle between British workers and those whose ancestors suffered slavery and colonialism and who today still suffer inequality, discrimination and “stop and search” by racist police. We do need “integration” – not into an idealised British nation but – into the part of the international working class that lives here or wants to live here.