By Dave Stockton

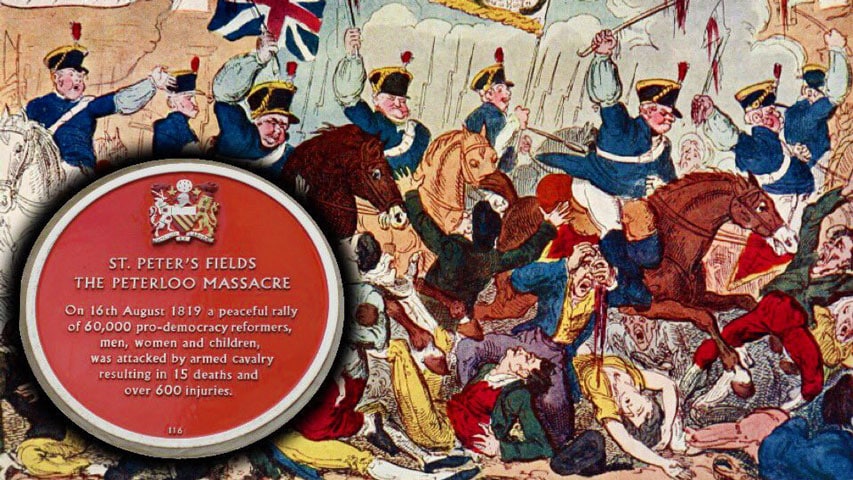

August 16 is the bicentenary of the Peterloo Massacre in which 18 people were killed and hundreds injured when soldiers attacked an unarmed crowd of 60,000 men, women and children peacefully demonstrating for the right to vote in Manchester.

Only now has any serious memorial to this event been erected in the city it in which it took place. Despite the thousands of pompous statues of monarchs, generals, and politicians littering our civic spaces, hardly one commemorates the big events of the long struggle for democracy against Britain’s rulers.

The Peterloo massacre was a defeat for Britain’s nascent workers’ movement. But as Rosa Luxemburg said, “where would we be today without those “defeats,” from which we draw historical experience, understanding, power and idealism?”

Peterloo commenced a century of struggles by working people that won us universal suffrage and legal trade unions and workers parties.

The great majority of those assembled in St Peter’s Fields on that day were working class men and women – handloom weavers as well as workers from the new mills that had sprung up over the previous decades of Britain’s industrial revolution.

The martyrs of that day, plus many victimised by their employers for taking part, deserve to be remembered equally with the Tolpuddle martyrs sentenced to transportation for organising a trade union.

Manchester and its surrounding mill towns was the very cradle of the industrial revolution. By 1813 there were 2,400 power looms operating in the city’s cotton mills, a figure that would rise to 14,000 by 1820. But twice as many workers were still labouring long hours at handlooms in their own cottages, their livelihoods undercut by mechanisation.

For the next few decades these workers formed the most radical, indeed revolutionary, section of a working class movement that was even then being born as small local, illegal, trades unions and even smaller sects of radicals and utopian socialists.

The long war with revolutionary France ended on the battlefield of Waterloo in 1815. Across Europe a period of reaction set in. It was soon followed by a chronic economic depression, which hit cotton and woollen weavers and spinners hard; wages fell from 15 shillings for a six-day week in 1803 to 5 shillings or fewer by 1818.

But Britain was not yet ruled by an industrial bourgeoisie, but by big landowners, who had in the previous half century, driven the peasantry off the land by enclosing the common fields and pastures that had dominated the country’s villages since the Middle Ages.

The two Houses of Parliament were a “house of landowners”. When the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815, triggered a collapse in agricultural prices, they passed the notorious Corn Laws which levied a tax on imported grain. The consequent rise in the price of corn, and thus of bread, added to the fall in wages, enormously increased the suffering of the urban and rural population.

An unrepresentative parliament

In 1819 Manchester had a population of 100,000, but like the expanding industrial cities of the midlands and north, it sent not a single member of parliament to Westminster. Lancashire as a county sent two but the small number of electors had to travel to Lancaster to cast their votes verbally at a public hustings.

Meanwhile Old Sarum, a windswept hill in Wiltshire on which stood only three houses, and which had ten voters, elected two MPs. Many such ‘rotten boroughs’, plus the county representatives, were completely in the pockets of the great landowners and rarely if ever had an actual election.

What competition for seats there was largely conducted by wholesale bribery and corruption not to speak of outright coercion. But such details hardly mattered since under three per cent of the adult male population in England and Wales, some 300,000 out of 8 million, had the vote. The proportion was even less in Scotland.

The chances of reforming the electoral system seemed bleak. Yet, in the 1780s and early 1790s Britain had seen a powerful movement headed by the reforming wing of the Whig Party led by James Fox, who wanted constitutional reforms, had sympathised with first the American and then the French Revolution, until it deposed and executed Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. But there were also far more radical elements, which aligned themselves with the French Jacobins.

Tom Paine ‘s pamphlet The Rights of Man (1791) written in reply to the Tory Edmund Burke’s reactionary Reflections on the Revolution in France of the previous year, became immensely popular for the next two generations of revolutionary and working class militants.

Mary Wollstonecraft, a colleague of Paine’s, wrote A Vindication of the Rights Of Women, in 1792. The so-called English Jacobins, made up of skilled workers or artisans, created a network of corresponding societies, which spread across the country modelled on the London Corresponding Society formed in 1791. They were so named because they sent political letters to one another to be read out.

The societies developed a programme of universal suffrage (or manhood suffrage as it often was termed), annual parliaments, the calling of a National Convention to draft a written constitution, and many of the social reforms that Paine included in his book, including progressive taxation, payment for the unemployed and pensions for the elderly.

Thomas Spence, another radical thinker, called for the confiscation of the great landed estates and common ownership of the land by village and farming communities.

But after the war broke out with revolutionary France in 1793 heavy repression rained down on them and the movement was crushed or driven deep underground in a period that has been called Pitt’s Terror.

Various conspiracies, many set in train by government provocateurs marked the later 1790s and many “Jacobins” were imprisoned for sedition, transported to Australia or executed for treason. Trade unions too were made illegal by the Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800, and the corresponding societies were suppressed. A genuine mass revolutionary uprising occurred in Ireland in 1798 but this too was put down with great bloodshed.

Reform movement

However, as the new century progressed, increasing participation by urban workers began to revive the reform movement. The Luddite movement of 1811-1813 was aimed at the employers who were introducing machinery to replace hosiery workers and handloom weavers.

It was suppressed. The Blanketeers attempted to march from Manchester to London in March 1817 to appeal to the Prince Regent against both mass unemployment and the suspension of Habeas corpus.

The procession was savagely attacked by the King’s Dragoon Guards, and many arrested. In many ways this was the direct precursor of Peterloo and shows the latter was no unique event in the history of how a minority of exploiters maintains its rule.

Britain had a Tory government under Lord Liverpool who was prime minster from 1812-1827. His ministry was stuffed with reactionaries – Lord Eldon as Lord Chancellor, Lord Sidmouth as Home Secretary, Lord Castlereagh as Foreign Secretary and the Duke of Wellington as Master-General of the Ordnance. Wellington’s remark “Beginning reform is beginning revolution” indicates the general philosophy of this regime.

In the following years not only was Habeas corpus suspended but a Seditious Meetings Act, passed in 1817, allowed the authorities to ban virtually any meeting they wished. In addition, government spies were sent into the industrial areas where discontent was rife and many acted as provocateurs, for example the notorious William Richards, known as “Oliver the spy”.

He encouraged the abortive Pentrich Rising in June 1817, the leaders of which were convicted of treason and sentenced to be hung, drawn, and quartered (though the quartering was remitted as an act of mercy by the Prince Regent, and the three men were beheaded after the hanging).

The massacre

In July 1819, the Manchester magistrates wrote to Lord Sidmouth claiming a “general rising” was likely, due to the “deep distress of the manufacturing classes” being fomented by the “unbounded liberty of the press” and “the harangues of a few desperate demagogues.”

They had already recruited 400 special constables armed with long wooden truncheons from amongst the local petty bourgeoisie – publicans, shopkeepers, lawyers, the sons of Tory landed gentry and factory owners – under the command of Manchester’s vicious deputy constable, Joseph Nadin.

They also deployed sixty mounted yeomanry from Manchester and had in reserve another 420 from Cheshire. As if this were not enough they deployed 340 regular cavalry, the 15th Hussars, plus 400 infantry and two six-pounder cannon. The total forces of “order” that day numbered some 1,500.

A less fearsome enemy for these warriors of the ruling class could hardly be imagined. A witness reported “crowds of people in all directions, full of good humour, laughing and shouting and making fun… it seemed to be a gala day.” Feeder marches came in from surrounding towns; Bury, Bolton and Rochdale. Large contingents of women – some 12 per cent of the total – all dressed in white joined in.

They came in well-organised contingents, thousands strong, carrying banners, surmounted with red woolen caps of liberty, and bearing the inscriptions, ‘no corn laws’, ‘annual parliaments’, ‘universal suffrage’, ‘vote by ballot’.

The local radical paper, the Manchester Observer, reported the objective of the meeting was “to take into consideration the most speedy and effectual mode of obtaining Radical reform in the Common House of Parliament” and “to consider the propriety of the ‘Unrepresented Inhabitants of Manchester’ electing a person to represent them in Parliament”. This latter proposal, without the Kings writ, had been declared a “serious misdemeanour” by the Home Secretary and rendered the meeting seditious.

Nevertheless, the meeting was not banned in advance nor was the Riot Act read at any point by a magistrate, which would have rendered the meeting illegal at once. Thus it was a legal, orderly and peaceful gathering that was attacked by the forces of disorder.

The famous radical leader Henry Hunt, known as orator Hunt, had hardly begun his speech before the mounted Manchester Yeomanry charged the crowd at a gallop, on the way knocking down a 23-year old woman carrying a baby, which fell from her arms and was crushed under the horses’ hooves. He was the first martyr of the day.

Hunt was eventually dragged from the hustings and made to run the gauntlet of constables to the house where the magistrates assembled, there to be felled by a savage blow to the head. Mary Fildes, a platform speaker for the women’s suffrage campaign was also battered about the head.

The Chairman of the Lancashire and Cheshire Magistrates, a local landowner named William Hulton, then shouted to the officer commanding the 15th Hussars: “Good God, sir! Do you not see how they are attacking the yeomanry? Disperse the crowd!” In the melee that followed more than 200 were sabred, 70 wounded by truncheons, and 188 trampled by the horses.

Repression and reaction

In the days that followed a sweep of known radicals was carried out and employers sacked workers they knew had been at St Peter’s Fields that day. One severely wounded man, when the doctor treating him asked to be assured he would never participate in such a gathering again, refused and was thrown out of the Manchester Infirmary to die at home.

On receiving news of the carnage in Manchester, the Prince Regent expressed to the magistrates his “great satisfaction at their prompt, decisive and efficient measures for the preservation of the public tranquillity”.

In fact, two small local risings, in Huddersfield and Burnley, plus the so-called Yorkshire West Riding Revolt, took place (or were provoked) during the autumn of 1820, along with the discovery and foiling of the Cato Street conspiracy to blow up the cabinet.

By the end of the year, the government had introduced legislation, later known as the Six Acts, to suppress radical meetings and publications, and every significant working-class radical reformer was in jail.

James Wroe, editor of the Manchester Observer, had dubbed the event Peterloo, an ironic reference to the battle of Waterloo. Amongst those fatally injured on August 16 was John Lees, a textile worker from Oldham and veteran of Waterloo, who before he died from his injuries, said to a friend: “At Waterloo there was man to man but there it was downright murder.” Wroe too paid for his insolence by being convicted of producing a seditious publication and sentenced to twelve months in prison and fined the then-exorbitant sum of £100.

Another dark period of reaction followed until the end of the 1820s saw a renewed and even more powerful movement for reform emerge, resulting in the Great Reform Act of 1832, which abolished rotten boroughs, created new constituencies, and slightly extended the male franchise.

But this movement too saw disappointment for the increasing numbers of workers who acted as the mass troops of reform. But this time the realisation that the middle classes- i.e. the industrial and commercial bourgeoisie- would always sell out or sell short their working class followers led to a movement – Chartism- far more definitely identified with the cause as that of the “unshaven chins, blistered hands, and fustian’ jackets.”

But the emerging class element, the demand for social justice, was already obvious to the poet Percy Shelley in his response to Peterloo. This can be seen not only in the famous conclusion to his poem The Masque of Anarchy, “Rise like lions after slumber…Ye are many they are few, ” which Jeremy Corbyn has brought to a new audience, but also in his Song to the Men of England.

Men of England, wherefore plough

For the lords who lay ye low?

Wherefore weave with toil and care

The rich robes your tyrants wear?

Wherefore feed and clothe and save

From the cradle to the grave

Those ungrateful drones who would

Drain your sweat—nay, drink your blood?

The seed ye sow, another reaps;

The wealth ye find, another keeps;

The robes ye weave, another wears;

The arms ye forge, another bears.

Sow seed—but let no tyrant reap:

Find wealth—let no imposter heap:

Weave robes—let not the idle wear:

Forge arms—in your defence to bear.

Conclusion

Events in Manchester two hundred years ago show how false is the claim that British democracy is centuries old. In fact the majority of working class men only received the vote in 1918 and universal suffrage only came with the enfranchisement of all women in 1928.

Peterloo also shows how little the rights we presently “enjoy” are the generous gift of “our” ruling classes. It reminds us that these rights had to be fought for by radicals and republicans – the extremists and troublemakers of their day. It reminds us too that the state is always the instrument of the exploiting and ruling classes and that an unarmed people, no matter how united, will always be defeated.

Bloody Sunday in Derry in 1972 when British paratroopers killed fourteen unarmed civilians, and police repression during the 1984-5 miners’ strike, shows that when challenged today’s rulers are every bit as vicious as their predecessors.

Last but not least it reminds us that the working class, the great majority of the people, is the agency through which all great political and social change has come and must come today.