Exhibition at Tate Britain London, running until 9 April 2024

Reviewed by Allison Balfour

This ambitious and very interesting show was for me a ‘blast from the past’ and for younger visitors it should be a real eye-opener. Works in the exhibition are made in a variety of media, including traditional painting, drawing, print-making, film and photography, but also use much more everyday materials associated with the home and ‘women’s’ work and skills, such as knitting, cooking, sewing, mending and cleaning.

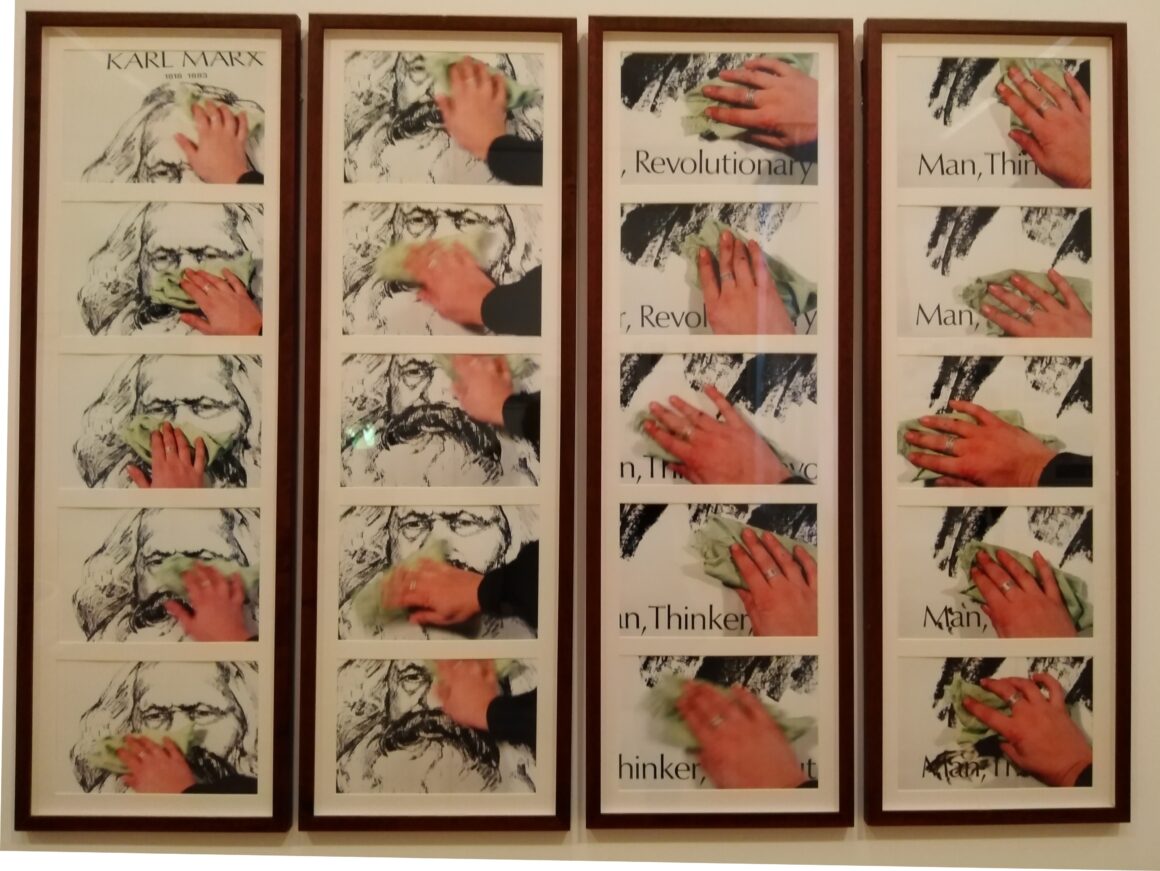

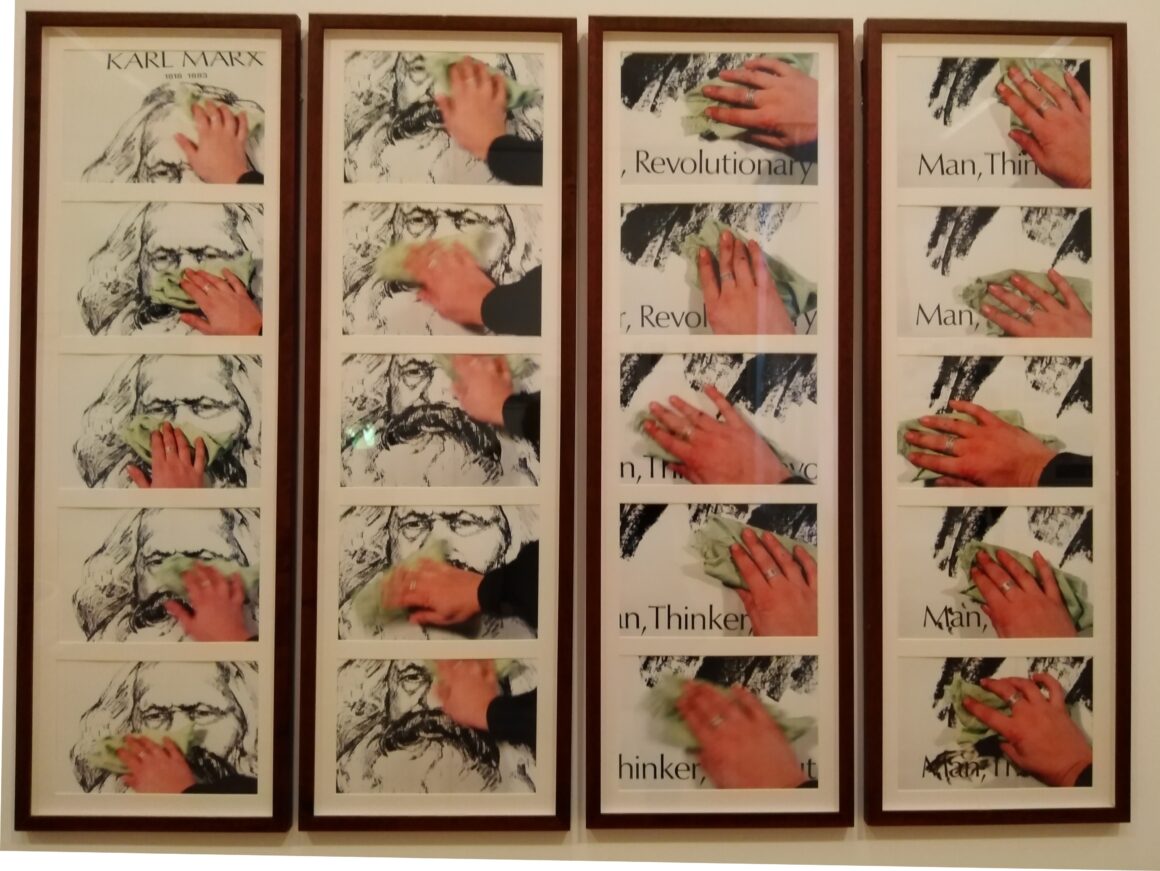

For example in the photowork illustrated below by Alexis Hunter, originally made in 1978, The Marxist’s Wife still does the Housework, a woman’s hand is shown cleaning an image of Marx with a rag which gradually wipes away his face. The label accompanying the work states that the title is ‘a reference to Marx’s failure to incorporate women’s work in the home into his theory of labour relations’.

While Marxists would counter this argument by pointing to the demand for the socialisation of domestic labour so the work of social reproduction is properly shared by society as a whole, which should be in every revolutionary programme, nevertheless Hunter’s piece does provoke reflection, debate and, as the show’s title suggests, activity and change.

The struggles of women expressed in the visual and material culture of the time also show how many women attempted to address a whole number of issues relating to social, economic, racial and sexual oppression. Demands for equal pay, free abortion and contraception, wages for housework, an end to the exploitation of women’s bodies, patriarchal culture, anti-war protests, the marginalisation of women artists, and lack of free or even affordable childcare all feature in the works on show.

While many of the works come from a feminist perspective and see men and patriarchy as the main oppressors, other works are fiercely critical of Margaret Thatcher, and some acknowledge the support of men. In Melanie Friend’s series Mothers’ Pride, from 1988, we witness the testimonies of teenage mothers having to give up educational opportunities due to pregnancies, lack of support from government, and often from home.

Works by photography collective The Hackney Flashers, including their famous campaigning photography, Who’s holding the Baby, 1978-80, documented women campaigning for childcare – ‘childcare is a question of money and class’. This is still the case today, arguably even worse.

Sections of the exhibition also cover mass women’s actions like the Greenham Common Peace Camp, and the women’s support groups in the Miners Strike 1984-5 and last but definitely not least, lesbian rights and identities, as with Rosie Martin’s photo and text works on the theme of ‘What does a Lesbian look like?’

An interesting aspect of this exhibition is the display of publications from the time, Shrew, Spare Rib, and many others produced as cheaply and quickly as possibly using stencils and duplicating machines. This seems like ancient technology now in the digital age!

Other works used cheap and easily available materials, which have degraded over time. For example Marlene Smith’s Good Housekeeping 111, (1985 remade 2023) includes J-cloths, used for cleaning, soaked in plaster, then dried. This installation commemorates Cherry Groce, shot by police who burst into her home in Brixton, leaving her paralysed. Her death led to angry uprisings against police disregard for Black lives. That hasn’t changed much either.

There is not much about trans women in the show; that is something that I think would be different if the show was covering the present time, when trans rights have become more visible and important, as well as being a dividing line between feminists who refuse to include transwomen in the category of ‘woman, and women who support transwomen’s chosen identities.

This is an exhibition, which has much to offer on many levels, and importantly it shows how much remains to be done to eradicate women’s oppression and exploitation in society. In some ways how little has changed for many women here in the UK and around the world. Art and activism still have an enormous role to play in the fight for equality and justice.