By Dave Stockton

The BBC’s decision to end this year’s Last Night of the Proms broadcast with an instrumental, rather than sung, rendering of Rule Britannia and Land of Hope and Glory provoked synthetic apoplexy on the front pages of the Daily Mail, Express and Telegraph.

By partially dispensing with what has long been considered an embarrassing anachronism, the broadcaster provided the Tories with the chance to strike back at what they regard as a campaign of liberal-left, politically correct attacks on Britain’s ‘culture’ and ‘heritage’.

Boris Johnson, sensing the opportunity to deflect the growing attention being paid to his criminal bungling of the pandemic response and the coming tsunami of unemployment, blustered his way into his very own culture war:

“I think it’s time we stopped our cringing embarrassment about our history, about our traditions, and about our culture, and we stopped this general fight of self-recrimination and wetness. I wanted to get that off my chest.”

Truly, few things in modern Britain are more embarrassingly cringeworthy than concluding a classical music concert with a crowd of drunken Tory yahoos braying out hymns to imperial nostalgia.

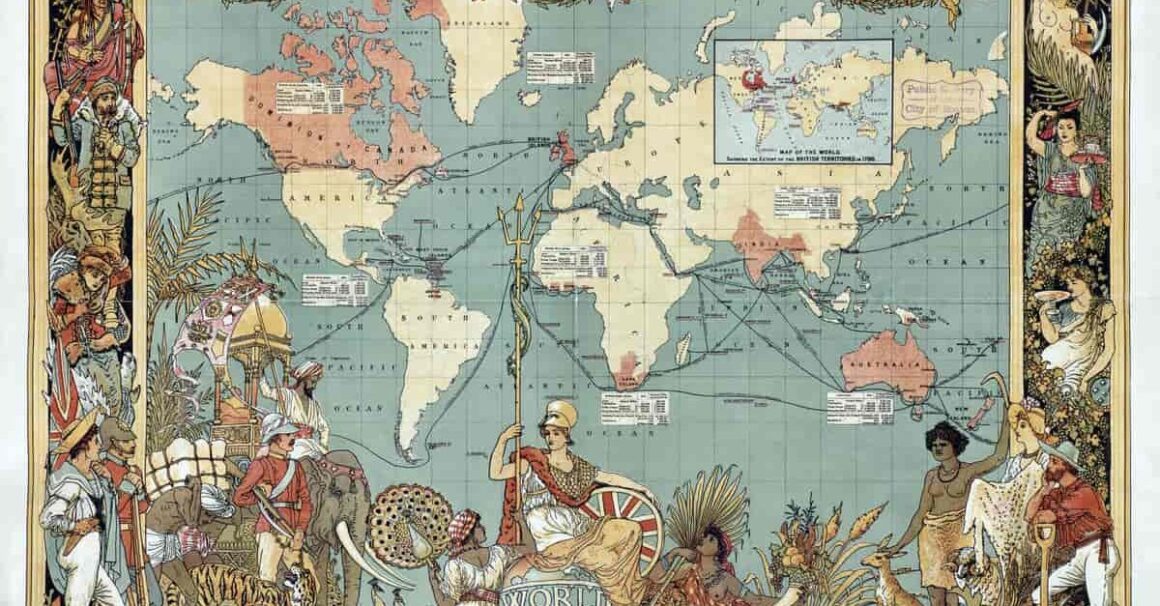

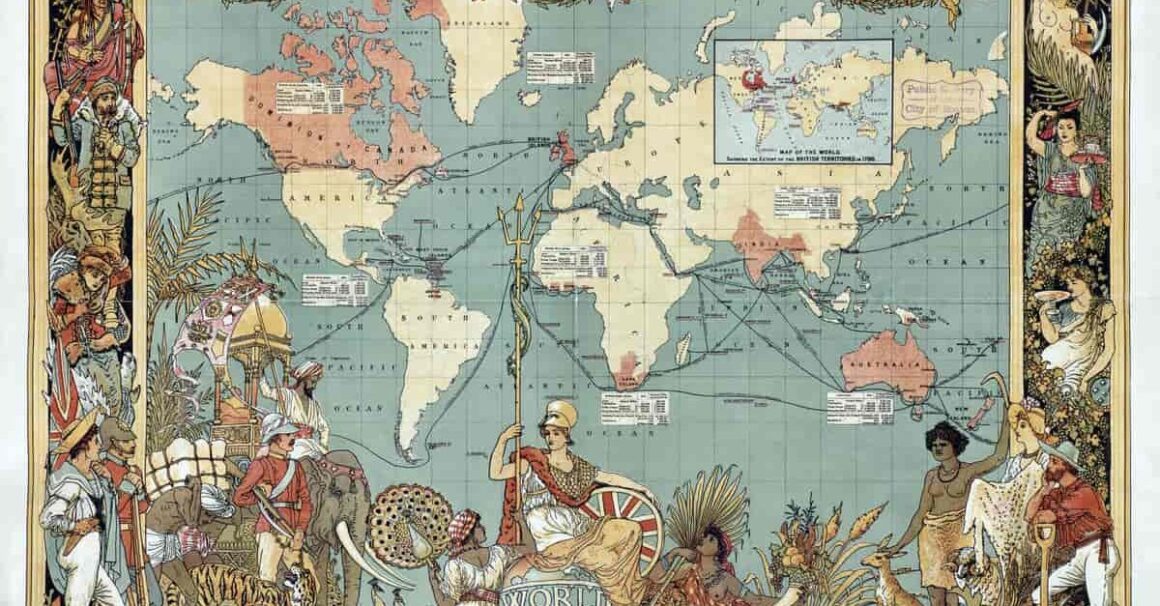

The ‘traditions’ and ‘culture’ that Johnson lauds are inextricably bound up with Britain’s pioneering role as slave-trader and coloniser, centuries of history so brutal and profitable that its geographical scars and spectacular wealth continue to distort politics on every continent.

Professor David Richardson has calculated that British ships carried in excess of 3.4 million Africans to the plantations of the Americas in the 250 years of the slave trade. By the mid 18th century – when “Rule Britannia” was first proclaiming “Britons never would be slaves”, 42,000 black slaves a year – over half the total – were being transported to the Americas on British ships.

As historian David Olusoga has shown in his book Black and British and his excellent TV series, Black British History We’re Not Taught in Schools, the classical buildings aping the ancient Roman slave state of our cities and the beautiful Palladian mansions and their splendid content that litter the English countryside were built on profits from the slave trade and forced labour on the Caribbean plantations of British aristocrats.

The so-called “culture wars” over monuments to slaveholders and imperialists, owe their origin to the demonstrations in Charlottesville, Virginia in August 2017 against the statute of Confederate commander-in-chief Robert E. Lee. White supremacists and fascists responded to this affront to racist sensibilities by mounting torch-lit parades with racist slogans directed against black and Jewish people. President Trump, like Johnson here, presents defending these monuments as a battle for “our culture.” To this we say – not our culture, but your barbarism.

Most of the statues glorifying Confederate “heroes” were erected in the decades after the civil war, during the darkest period of the “Jim Crow” laws when the black population of the southern states were disfranchised and terrorised by lynch mobs and the Ku Klux Klan.

The Black Lives Matter Movement in the USA, which reignited after the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 26, has inspired a global movement raising not only the killings and systematic harassment of black people (and other “racial” minorities) but all forms of discrimination, including monuments glorifying open racists and an absence of the recognition of the achievements of people of colour.

When BLM spread to the UK it targeted the monuments to our rulers’ own historical complicity in slavery. When the monument to Bristol slave trader Edward Colston was pulled down and thrown into the harbour, Boris Johnson (and senior Labour Party figures) denounced the protesters and called it “a criminal act”.

In Oxford, there has been a long-running campaign to remove the statue of arch-imperialist Cecil Rhodes at Oriel College. Rhodes, though a Liberal and supporter of Irish Home Rule, was the principal advocate and hands-on pioneer of Britain gaining the “lion’s share” in the carve-up of Africa in the late nineteenth century, when all the major European powers, the USA and Japan began to seize “unoccupied” territories in a ferocious competition for empire that concluded with the barbarism of the First World War and the establishment of European colonies in the Middle East.

The 1899-1902 Boer War, which Rhodes played a major part in fomenting, was aimed at seizing the mineral wealth of Southern Africa — gold, diamonds, coal and copper — as well as the richer farmlands further north, in what became North and South Rhodesia (Zambia and Zimbabwe). The latter was allocated to white settlers after the African owners were driven out or reduced to landless farm labourers.

The Russian revolutionary and theorist of imperialism Vladimir Lenin quotes a revealing statement of Rhodes that shows the dual purpose of imperialism — the accumulation of capital and the softening of class antagonism in the imperialist homelands:

“… Cecil Rhodes, we are informed by his intimate friend, the journalist Stead, expressed his imperialist views to him in 1895 in the following terms: “I was in the East End of London (a working-class quarter) yesterday and attended a meeting of the unemployed. I listened to the wild speeches, which were just a cry for ‘bread! bread!’ and on my way home I pondered over the scene and I became more than ever convinced of the importance of imperialism… My cherished idea is a solution for the social problem, i.e., in order to save the 40,000,000 inhabitants of the United Kingdom from a bloody civil war, we colonial statesmen must acquire new lands to settle the surplus population, to provide new markets for the goods produced in the factories and mines. The Empire, as I have always said, is a bread and butter question. If you want to avoid civil war, you must become imperialist.” (Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism)

Rhodes died in March 1902, stating in his will: “I contend that we are the first race in the world, and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race. I contend that every acre added to our territory means the birth of more of the English race who otherwise would not be brought into existence”.

The famous Rhodes scholarships at Oxford were designed to develop an elite of “philosopher kings” who would rule America and eventually bring it back into the British Empire.

Land of Hope and Glory, written for the coronation of the ‘King-Emperor’ Edward VII, was the anthem of this period of imperialist plunder. It was written just after Britain’s Boer War victory in which there had been scenes of hysterical patriotism in the streets of London (Mafeking Night), of which the Last Night of the Proms is a distant echo. The first performances of the two patriotic anthems began in this period and the BBC started broadcasting them in the 1920s.

But they only became a national institution under the baton of the conductor Sir Malcolm Sargent from 1952 onwards. Ironically, the ritual bellowing of “wider still and wider shall thy bounds be set” grew all the louder during the period of colonial liberation struggles when those bounds were becoming smaller and smaller.

As for Boris Johnson, biographer of noted racist and fervent imperialist Winston Churchill, whose own racist views on the former subjects of the British Empire are well documented in his mocking of “flag-waving piccaninnies” with “watermelon smiles”. Confirmation, if it were needed, is provided in another column in which Johnson wrote that seeing a “bunch of black kids” made him “turn a hair”, adding “if that is racial prejudice, then I am guilty”. Quite!

His yearning for the great days of Empire is often expressed in suitably offensive terms. In 2010, on hearing that former US president Barack Obama had removed a bust of Churchill from the Oval Office, Johnson commented, “The part-Kenyan president [has an] ancestral dislike of the British Empire – of which Churchill had been such a fervent defender.”

In language more suited to 1902 than 2002, he used a Spectator column to argue that “the problem is not that we were once in charge, but that we are not in charge anymore. The best fate for Africa would be if the old colonial powers, or their citizens, scrambled once again in her direction; on the understanding that this time they will not be asked to feel guilty.”

All this pathetic nostalgia for Empire is a thin veil for modern racism. Why should the British children and grandchildren of people who came from the Caribbean, African and Indian colonies be taught only of the achievements of the slave traders and slave owners, of the colonialists and imperialists who plundered their ancestral homes? Why too should white British children whose ancestors at the same time were being deprived of their communal lands and driven by hunger into the new factories or forced by poverty to emigrate to the colonies learn that the Clives, Nelsons and Wellingtons of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were somehow doing it for them?

Where are the monuments in central London to the figures of the labour and democratic movements like the Chartists — including the black militant William Cuffy — who fought for the right to vote when scarce one fifth of the population enjoyed it? The culture of the nation is the culture of the ruling class shot through with racism. The culture of the working class, if it is true to its real class interests, is international and antiracist.

Land of Hope and Glory and Rule Britannia are paeans to Britain’s imperial status, built over the bodies of black slaves and white proletarians. It is not “our culture” but the culture of our ruling and exploiting class. We do not want to ‘forget’ or ‘cover up’ the legacy of Britain’s role in slavery – but we do insist that the glorification and celebration of Empire in events like the Last Night of the Proms should cease and the whole truth of the British ruling class’s plunder of the world should be told.

To achieve a decisive reckoning with the past, and chart a path to uprooting the racist foundations of today’s society, we need a materialist, scientific understanding of the forces shaping our history. The slave trade and the British Empire were not the product of evil people, although there were plenty on hand to accomplish it. It was a necessary process in the formation of capital and a fully developed industrial and financial capitalism, known as ‘primitive accumulation’.

Here is how Karl Marx evocatively described this process in his great work Capital:

“With the development of capitalist production during the manufacturing period, the public opinion of Europe lost its last remnant of shame and conscience. The nations bragged cynically of every infamy that served them as a means to the accumulation of capital. Read, for example, the naïve commercial annals of the worthy A. Anderson. Here it is trumpeted forth as a triumph of English statesmanship that, at the Peace of Utrecht, England extorted from the Spaniards the privilege of being allowed to ply the slave trade, not only between Africa and the English West Indies as hitherto, but also between Africa and Spanish America. England thereby acquired the right to supply Spanish America until 1743 with 4,800 negroes yearly. …

“Tantae molis erat, [This was the great effort necessary] to establish the ‘eternal natural laws’ of the capitalist mode of production, to complete the process of separation between the workers and the conditions of their labour, to transform, at one pole, the social means of production and subsistence into capital, and at the opposite pole, the mass of the population into wage labourers, into the ‘free labouring poor’, that artificial product of modern history. If money, according to Augier, ‘comes into the world with a congenital blood-stain on one cheek,’ capital comes dripping from head to toe, from every pore, with blood and dirt.”

In overthrowing capitalism we will have to hose down that filth and blood to reveal a world fit for all nations and peoples to live and thrive in. Boris Johnson and his “hope and glory” racists will have no part in it.