As Black History Month commences, it is appropriate to reflect on the persistent need for systemic changes to our education system to ensure equality for students in marginalised communities. While there has been significant increases in the number of BME students entering university, we also know they are less likely to attend prestigious universities, less likely to complete their degree programme and less likely to qualify with top degrees than white peers with the same A-level grades.

Research published by Universities UK (UUK) and the National Union of Students (NUS) last year cast the curriculum as central to the experiences and progression of BME students, noting: “University leadership teams are not representative of the student body and some curriculums do not reflect minority groups’ experiences”.

And it is not limited to students. BME staff are also underrepresented in the Higher Education sector. Research by the University and College Union (UCU) found that 84% of academic staff and 93% of university professors were white. BME university staff faced a pay gap of 9% compared to their white colleagues.

In this context, a range of student-led campaigns have emerged asking challenging questions of their disciplines and institutions, drawing attention to the whiteness of education structures, curricula and teaching staff. Calls to ‘decolonise’ Higher Education and the curriculum have been growing as both staff and students have increasingly begun to interrogate race and ethnicity in their own disciplines.

However, this has also been accompanied by attempts to whitewash the academy’s historic role in intellectualising and justifying racism. Recent examples include a eugenics conference at University College London and the backlash against the ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ campaign at Oxford. When the Cambridge academic Dr Priyamvada Gopal challenged Niall Ferguson’s bullish assertions about the greatness of Britain’s imperial project on Radio 4, she received rape as well as death threats.

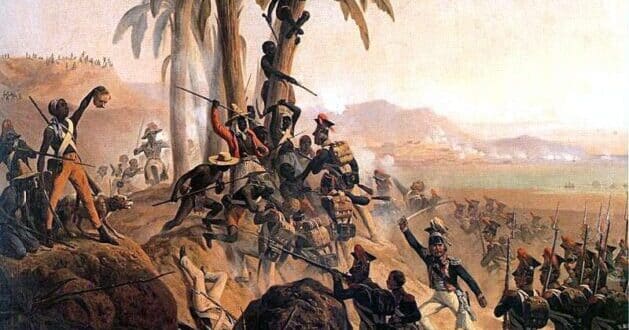

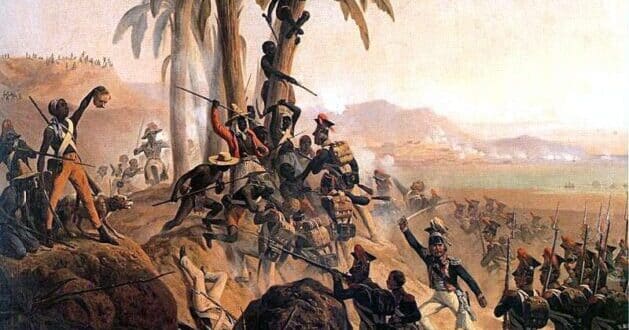

These institutions have legitimised reactionary views on colonialism which abound in the UK. Blind patriotism and a toxic imperial nostalgia at all levels of society frames the British Empire as something to be celebrated. A YouGov poll in 2019 found that a third of the people in the UK believe Britain’s colonies were better off for being part of an empire: a higher proportion than in any of the other major colonial powers. This raises serious questions about British education on colonial topics. People from India, Ireland, Kenya, Malaysia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe need no reminding of the realities of the British Empire.

Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson exploited this emotional nostalgia for their own political interest during the Brexit referendum campaign, opening a Pandora’s box of racism as hate crimes surged by 42% in England and Wales. Labour leader Keir Starmer has now replaced left-wing policies from the Corbyn era with similar appeals to patriotism, inevitably leading to the majority of the Parliamentary Labour Party abstaining on a bill which seeks to exempt British troops from prosecution in relation to torture and war crimes. This came a week before the announcement of the Public Prosecution Service that no further former soldiers will face criminal charges for the murder of 13 civil rights protesters during Bloody Sunday in Derry.

Anti-capitalist materials banned

Any criticism of the capitalist status quo has now been classified by the Department for Education (DfE) as an “extreme political stance”. A ban on resources expressing anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist sentiments in the classroom immediately causes issues for our History, Politics and Sociology departments, but more significantly, it also warrants a ban on teachers inviting young people to think critically about colonialism and racism, and explore different ways to respond to our current economic, political and ecological crises. The Coalition of Anti-Racist Educators (CARE) and the Black Educators Alliance (BEA) are taking legal action against the guidance to school leaders, arguing that it is a “thinly veiled attack on a wide range of movements fighting for urgently-needed social justice causes”.

The income-gap between the rich and poor remains high by historical standards following years of austerity and wage stagnation, with younger people more adversely affected by poverty and debt, a weak jobs market, poor housing and cuts to public services. Many of them have concluded the current system is rigged against them, leading the increasingly authoritarian Conservatives to scapegoat teachers and accuse them of “indoctrinating children”.

Our curriculum and educational institutions, both in secondary education and at university, have established a civilisational and racial hierarchy that places Western imperialism as a universal benchmark for enlightenment and progressive thought. The DfE guidance that schools should not promote “victim narratives that are harmful to society” is seeking to prohibit discussion about the conjoined twins of capitalism and racism.

Only a fifth of UK universities have committed to updating their curriculum to address the destructive legacy of colonialism and present-day racism. Decolonising the curriculum goes beyond adding black and non-western scholars to reading lists, but decolonising education itself, so academics and students not only question but challenge structural inequalities that perpetuate the attainment gap, rather than preaching the neoliberal virtues of ‘resilience’ and ‘hard work’.

Decolonisation should also be dedicated to abolishing tuition fees and ensuring universities are more accessible to the communities they serve, solving the hardest social problems across all cultural divides and involving the non-university parts of the population that have been left out. The hierarchical model of secondary education and private schools should also be abolished with their investments and properties redistributed to the state sector.

Decision making in schools, colleges and universities should be in the hands of elected committees of staff and students, empowering them to challenge and overturn forms of class, gender and racialised disadvantage in education. BME staff and students are most likely to identify these hierarchies explicitly. Ultimately socialists struggle for a liberation-orientated education system which offers all staff and students the opportunities to work against structural oppression and the tools to achieve their emancipation.