IT’S POSSIBLE to boil down the premise of each episode of Black Mirror into a single question: “What if you could upload your co-workers into a Sims-like simulation and make them do whatever you wanted?” (USS Callister), “What if you could put an implant in your child so you could monitor everything they do?” (Arkangel), “What if there was a machine that could download your memories?” (Crocodile).

In the new six-part series currently streaming on Netflix, writer and social critic Charlie Brooker explores these concepts and more via a series of cautionary tales.

USS Callister is a piercing critique of video game fandom and nerd culture in general. Reclusive game developer Robert Daly is frustrated that his co-workers do not respect him, so he creates a digital copy of their minds and uploads them into a Star Trek-esque game. In this universe of his own creation, Daly is a wrathful god who coerces his digital playthings into acting out parts in a misogynist, white supremacist fantasy role-play.

Brooker constructs his narratives by looking at current events and accelerating them to their most horrifying potential. Note the emergence of 2012 online game “Beat Up Anita Sarkeesian” featuring the feminist video game critic of the same name – viewed as a hate-figure by reactionaries in the gaming community – where players make Sarkeesian’s face more bruised and bloody with each mouse click. It isn’t far-fetched to observe this behaviour and extrapolate it into the grim tale told in USS Callister.

But the pitfall of this episode is that it doesn’t confront the root structural problems behind what is presented. The vast majority of the episode takes place in the game world and focuses on the fates of these digital beings, with little to no attention paid to what becomes of their counterparts in the real world. In a setting with no real-world consequences, the story fails to properly engage with contemporary issues, such as the marginalisation women and people of colour face in the real world of corporate games and software development.

Corporate power

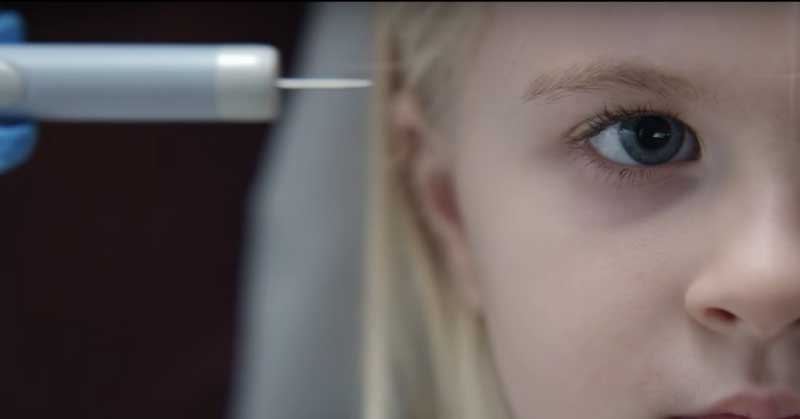

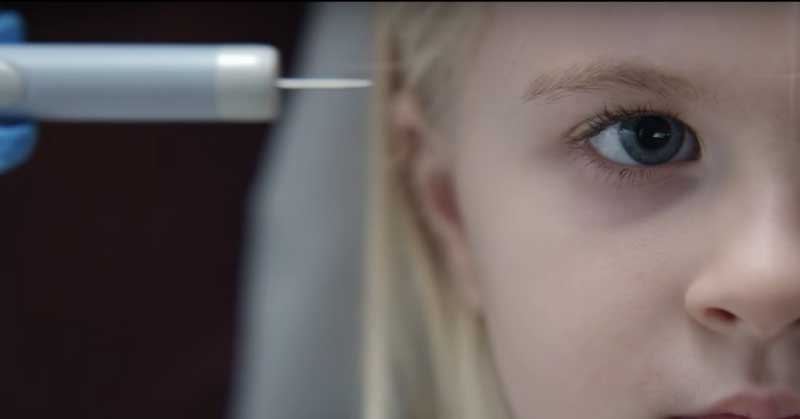

Arkangel is an indie-style drama set in the us suburbs that slowly spirals into a psychological horror. Overly protective single mother Marie Sambrell gets a tech company to install a microchip in her daughter’s brain, allowing her to see everything her daughter sees. The mother’s caring instinct gradually morphs into a malevolent drive to surveillance and control, resulting in tragedy.

The episode is gripping and stunningly directed by Jodie Foster, but again Brooker dodges a pertinent issue: corporate power. Last year, leaked documents revealed that Facebook had told its advertisers it could identify when users as young as 14 were feeling “insecure” or “worthless”. Advertising algorithms can easily manipulate this data to profit off vulnerable teenagers. In a world where tech companies are exploiting our children in such a way, is an overzealous helicopter parent the most important or relevant target for a cautionary tale about abuse of technology?

The same can be said for Crocodile. Architect Mia Nolan covers up a murder, but crosses paths with an insurance investigator conducting mandatory memory scans on witnesses of a road accident. I’m completely baffled as to why Brooker depicted such an abhorrent overreach of government power — literally having the legal right to search your citizens’ minds — and presented it as a means to capture a murderer, as if trying to persuade us of its necessity! (Contrast this with how Channel 4’s Electric Dreams portrayed the terrors of telepathic interrogation in chilling and well-executed fashion in The Hood Maker).

There is no real exploration of how oppressive this Orwellian mind-reading society is, or how people would suffer with such downtrodden civil liberties. Instead, yet again, a bad person does a bad thing.

Individuals or capitalism?

The final episode, Black Museum, is something of an improvement because it features sinister medical company TCKR, which trials unethical new technologies on unsuspecting innocents. But most of the wrongdoing is again perpetrated by ordinary people rather than TCKR itself.

Brooker reveals his thinking in a recent BBC interview: “In our stories technology is never the villain. It’s about giving an individual great power but if that individual is weak or has a flaw that’s where the problem comes in, it’s not generally inherent in the technology itself.” Brooker is ostensibly a liberal, obsessed with the failings of individuals as opposed to the failings of social relations. Brooker’s antiheroes are blessed with the gift of technology, but squander it and descend into a Faustian abyss of failure with nobody to blame but themselves.

Since it first darkened our screens in 2011, Black Mirror’s goal has been to show us a warped reflection of ourselves, to examine how our society is changing at a terrifying pace and not all of it for the better. But we don’t need a TV show to tell us that ordinary people are getting a raw deal in the information revolution; that’s painfully clear to any Amazon warehouse worker.

Of course, Brooker is correct that technological advances don’t inherently lead to a worse society. As socialists we don’t fear new technologies, from political organising apps such as Loomio to the benefits of social media in giving the masses a global platform. However, unchecked within a capitalist system certain technologies grant the capitalists and governments – who monopolise the production and deployment of those technologies to maximise profits and defend the rule of their class – immense power. It is the power of the ruling class that must be feared and challenged, not technology itself.