By Dave Stockton

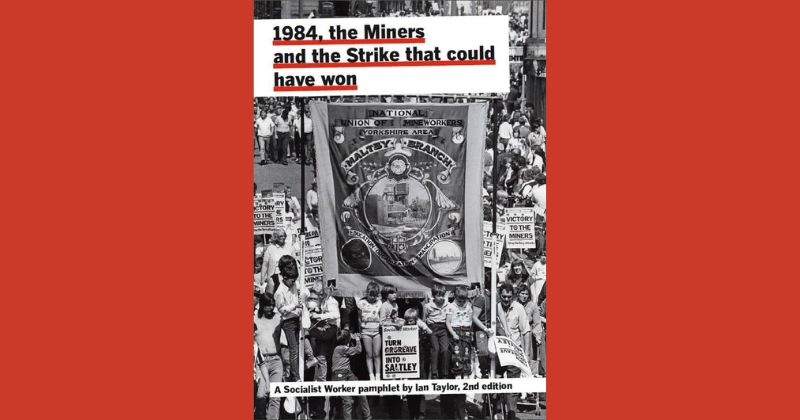

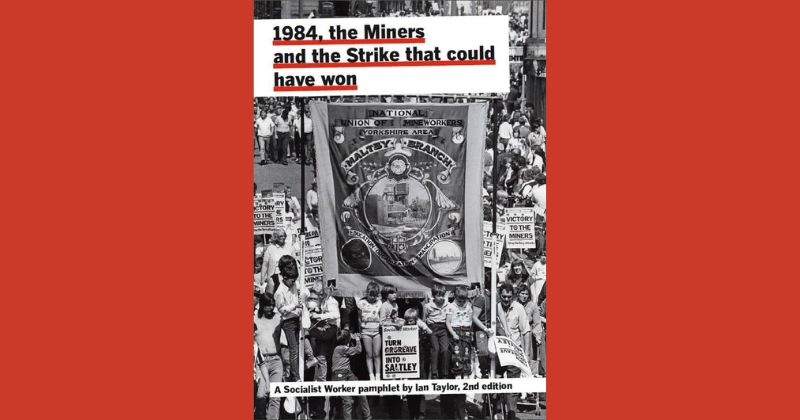

A review of 1984, the Miners and the Strike that could have won, Ian Taylor, Socialist Worker, 2nd edition, 2024, 60 pages, £3.

THIS IS a lively account of the famous year-long strike drawing on the voices of pickets, the women of the mining communities and those who supported the miners throughout the longest strike in British history. We hear the voices of their children too, who endured the occupation of their pit villages and saw their fathers well as their mothers assaulted and arrested.

What you will not find in this pamphlet is how this strike could have won. Instead it states that victory was denied, ‘because of a failure by the leaders of other unions to match the defiance of the miners and deliver solidarity crucial by blocking power and steel production. Solidarity action strikes and protests by other workers could have overwhelmed the government police and courts.’

This of course is correct; hindsight gives 20/20 vision. But the SWP at the time did not argue for the tactics and forms of organisation required to overcome the sabotage of the top union leaders and the TUC. They abstained from the fight for bodies that could have mobilised the rank and file of the key unions—the dockers, railway workers, steel and power workers—to take action with or without their leaders.

Workers Power, with far fewer members, did argue for and help set up the miners’ support committees that spread over the entire country. The SWP kept clear of them for six whole months, mocking them as ‘collectors of baked beans’.

Since 1982 they had been arguing that rank and file organisation was impossible given the weakening of the shop stewards’ movement. They even closed down their own rank and file front organisations. However, when they finally turned up to the support committees in September, they argued that they should concentrate on… collecting food and money and that to call for industrial action was utopian.

Arthur Scargill, for all his undoubted courage on the picket line, did not have the political courage to call for solidarity action, let alone to demand the TUC organise a general strike. He never condemned his fellow bureaucrats, however cowardly they were.

The SWP were blinkered by their founder Tony Cliff’s downturn theory, which meant they limited themselves to what they judged could be done—or rather what could not be done. In April 1984 Cliff wrote, ‘The miners’ strike is an extreme example what we in the Socialist Workers Party have called the downtown in the movement.’

What was the basis for this ‘theory’? Cliff claimed that, whereas the victories of the first half of the 1970s constituted an upturn, because the employers were on the offensive in the 1980s and workers on the defensive, this was a downturn.

To say this of a year which would see 26 million working days of strike action was incredible, not to mention the other bitter mass strikes of the 1980s. Yes, they all went down to defeat—because each fought alone.

Yet strangely this ‘theory’ is not mentioned in the pamphlet. Though Taylor does draw the lesson for today that rank and file organisation holds the key to overcoming the union leaders’ lack of militancy, in 1984 they argued that it was impossible to buld one. This month Workers Power are publishing our own pamphlet on the Great Strike which concentrates on the tactics and strategy that could have won.