By Tim Nailsea

At this point in the general election campaign it has become clear that Keir Starmer and the Labour Party are on track for a large, potentially historic majority. However, there is already a strain between the leadership and the left, as well as parts of the party’s base, especially Muslim voters.

The leadership’s witch-hunt against the left has alienated many activists and supporters from the party’s 2015-19 left swing, as has Starmer’s abandonment of almost all of Corbyn’s politics (and Starmer’s own pledges when standing for leader). Labour’s support for Israel’s ethnic cleansing of Gaza was the final straw for many, who have now abandoned Labour and are looking for a new home.

For some of those left-wing refugees from Labour, the Green Party is looking like an increasingly attractive prospect. A social democratic economic policy, well left of the Labour Party in many respects, a pro-ceasefire position on Gaza and a clear focus on the need to combat climate change – all stand in stark contrast to Labour’s neoliberalism, imperialism and pro-Zionism.

Some key figures from the Corbyn years, such as Guardian columnist Owen Jones and Novara Media’s Aaron Bastani, have declared their support for the Greens. Jo Bird, a former Labour left NEC candidate witch-hunted by the Labour right, is standing in Birkenhead for the Greens.

The promise of a Labour victory has led some to feel it is safe to vote Green without the fear of letting the Tories in. The Greens are likely to hold Brighton Pavilion and threatening to take Bristol Central from Labour’s Thangham Debbonaire, the Shadow Culture Secretary. They are also targeting two rural constituencies – Waveney Valley in East Anglia and North Herefordshire.

Evolution

The Green Party has long been on the periphery of British politics. It was begun in 1972 – first called the People’s Party, later the Ecology Party – by two solicitors concerned about population growth. Its original leaders were rabid opponents of socialism. As the Ecology Party it maintained its reactionary focus on population growth well into the 1980s.

The reason for this peculiar reactionary beginning is that, until the 1990s, the environmentalist movement remained largely a fixation of middle-class hobbyists and some enlightened academics. The true effects of climate change were yet to be understood by the mass of the population, and thus lifestylism and reactionary obsessions tended to predominate.

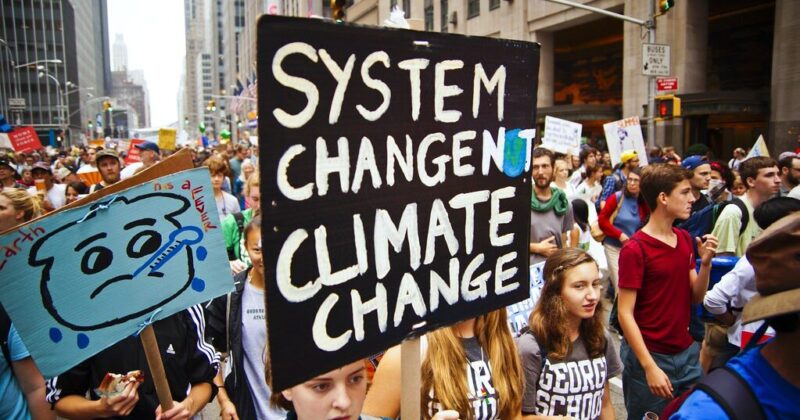

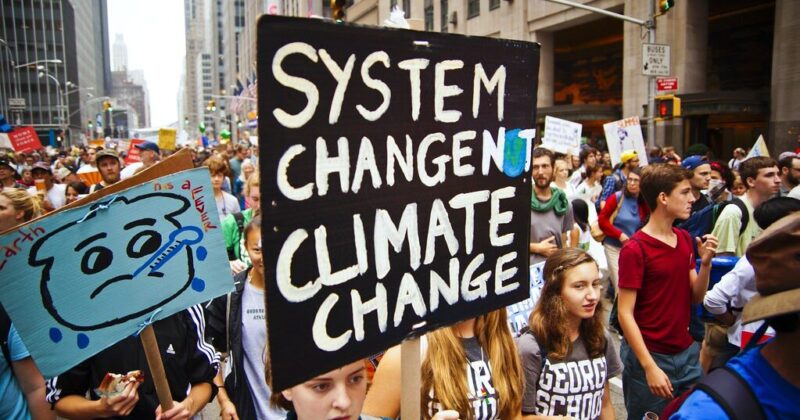

The change in the Green Party reflects the evolution of the environmentalist movement. Concerns about climate change have steadily moved up the list of people’s political concerns in recent years, particularly amongst the youth. As this happened, the Greens have shifted their programme from one of middle-class cranks to a more mainstream, liberal democratic party.

With the election of Caroline Lucas and Jean Lambert as MEPs in 1999 and Lucas as an MP in 2010, the Greens are now a fixture of national politics, and have largely positioned themselves to the left of the Labour Party on policy.

There are, however, some notable limitations to its leftward shift. Its record in local government is far from radical. In many councils, such as Brighton, the Greens have implemented austerity budgets and fought against strikes.

Programme

The Greens’ manifesto is pretty much a blueprint for environmentalist Keynesianism, where state intervention is used to transition the economy away from fossil fuels and to alleviate the worst effects of capitalism on people’s welfare.

Their housing policy promises to provide new social housing, introduce rent controls and reduce emissions. They also promise that greater fuel economy would reduce fuel bills. They pledge more investment in the NHS, education and care; nationalisation of railways, water companies and the Big Five energy companies; repeal of anti-union legislation; increase in the minimum hourly wage to £15; and a move to a four-day working week.

To pay for the increased spending, the Greens promise a wealth tax of 1% annually on assets above 10 million, 2% on those above 1 billion.

For all the mild social democracy, much of the Greens’ politics remains bogged down in localism and utopian tinkering with the capitalist system. Their manifesto claims that ‘small and medium businesses’ – not workers – ‘are the lifeblood of our economy and our communities’, and promises to build ‘regional mutual banks’ to help them.

The Greens call for an immediate ceasefire in Palestine, to end arms for Israel, and demand an end to the occupation of Palestinian land. They also pledge to cancel Trident. However, they argue that NATO ‘has an important role’ to ‘respond to threats’ and claim they would ‘work within it’ to focus on ‘global peacebuilding’. This, of course, is liberal nonsense. NATO is a military alliance of imperialist states. It does not respond to threats or build peace; it enforces the interests of Western imperialism through military means.

Ironically, one of the weakest aspects of the Greens’ programme is the environment. They advocate a shift to renewable energy, and a phasing out of fossil fuels. But they make little attempt to address how this would be carried out when faced with the inevitable concerted resistance of the capitalists.

The fact remains that the climate crisis is the result of an economic system that can only survive through continued exploitation and devastation. Capitalism’s search for surplus value means that long term considerations of the ultimate source of all wealth – nature and human labour – are swept away as minor concerns to be picked up by someone else or not at all.

To stop climate change, capitalism will need to be abolished and replaced by social ownership and democratic planning. To achieve that the power of the capitalist class will need to be smashed. This won’t be achieved through a 1% wealth tax or a few mutual banks.

The terms ‘capitalism’ and ‘class’ rarely enter any of the Greens’ speeches, literature or manifesto. They ultimately believe that the aims of their movement can be achieved through some relatively mild reforms, which amount to little more than ‘better’ management of the capitalist system. Despite the popularisation of environmental issues and the Greens’ shift to the left in policy, they remain at heart a middle class liberal party, not a working class socialist one.

Party and class

The Greens have identified four target constituencies for this election campaign. Brighton Pavilion and Bristol Central are urban centres, the latter a traditional Labour stronghold. Waverley Valley and North Herefordshire, however, are rural, traditionally conservative seats.

Environmentalism is not an issue for the working class alone. Many middle class conservatives fear the effects of climate change. The environmentalist movement is an eclectic mix of radical anti-capitalists, urban liberals and middle-class anti-development NIMBYs. The Green Party rests on, and reflects this movement.

Their middle class base and commitment to electoralism mean that the Greens promise voters a kinder, gentler capitalism, with a touch of green. The Greens do not even claim to be a socialist party. They do not raise the issues of class or capitalism. They are openly pro-capitalist, and middle class in composition.

The working class does need a radical alternative to the Labour Party. Any such party must have a serious programme to tackle the climate crisis. The Green Party is not that party. We cannot tail a party set up by and for the middle class. As workers we must build our own party, with our own programme that represents our own interests.

In this election there is no such party or even a serious move to build one. Therefore we advise class conscious workers to vote Labour and prepare to fight Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves as soon as they enter Downing Street.

Only by putting the Labour Party to the test of office and demanding they carry out serious pro-working class reforms, can socialists open up divisions inside the party and between the parliamentary party and the unions, paving the way for a new workers’ party.