By Andy Yorke

Russia is one of what Lenin called the great powers—in reality great robbers. The country is militarily strong (with the largest nuclear arsenal and the second largest armed forces in the world) but economically weak, accounting for only 1.9% of the world economy. Because of this mismatch it has increasingly allied itself with the economic powerhouse of China.

Together they present a challenge to the United States, still overwhelmingly the world’s most powerful imperialism, but with a hegemonic role over the imperialist powers in the European Union. The new Cold War between these camps is a product of the intensification of inter-imperialist rivalry over control of the world’s markets, natural resources and sources of profit.

The peculiar features of Russian imperialism today have their roots in its past as the Soviet Union and the way that capitalism was restored. After the 1991 collapse of the USSR, neoliberal shock therapy (largely planned by US economists) plunged the country into the deepest depression in its history, with GDP halving from 1990– 1997 and hyperinflation destroying the currency. The state-owned economy was privatised by a new class of bureaucrats-turned-billionaires—the so-called oligarchs—and prostrated before Western multinationals.

In contrast, China has had a controlled, decades-long transition to capitalism, protected from the world economy in order to develop a diversified, imperialist economy, tapping sources of capital in the Chinese diaspora and existing in a two decades long synergy with the USA as a manufacturing centre for the latter’s capital. Russia has been unable to accumulate the capital to follow China’s path and break out of the economic mould set by the USSR with its narrow emphasis on military production and energy exports. There are no Russian Huaweis, and Lada is owned by Renault—Western and Chinese multinationals dominate consumer markets.

Putin’s election in 2000 marked a turning point after the economic chaos arising from the reintroduction of capitalism and so for many Russians he was seen as a saviour that pulled the country back from the brink of collapse. He broke the political power of the biggest oligarchs, and brought the energy sector largely under state control, with booming oil prices allowing an economic recovery. But his increasingly authoritarian, Bonapartist regime—itself a reflection of Russian capitalism’s weakness—and falling oil prices after 2008 meant increasing popular opposition, itself requiring further repression to maintain control.

Russia under Vladimir Putin and China under Xi Jinping are often referred to by commentators as ‘revisionist powers’, because they seek to ‘revise’ the hugely favourable balance of wealth and power which the USA achieved with the downfall of the Soviet Union in 1991. China has, thus far, done so by its spectacular growth rates, becoming the workshop of the world. Russia necessarily seeks to translate its military power and its geographical location into economic power, by linking up with China.

Russia lost the Soviet Union’s dependent countries in Eastern Europe with the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact followed by the dissolution of the Soviet Union. This meant it lost direct control over Ukraine, Belarus, and a series of states in the Caucasus and Central Asia, but did all it could to retain them as semi-colonies, independent politically but tied into Russia’s economic and security needs. Thus it looked askance at the growing influences of both the European Union and Nato in these countries and the overthrow of regimes friendly to Russia by so-called colour revolutions in the first decade of the new millennium.

The United States works on the principle that what’s mine is mine and what’s yours is a matter for negotiation. Russia, under Putin, sought to deepen integration and exploitation of the former parts of the Soviet Union. Ukraine, with its iron ore and gas reserves and highly fertile agricultural land is a lucrative target for any imperialist country. Indeed sections of the Russian ruling class have never accepted its ‘loss’ as can be seen by Putin’s recent speeches, claiming Ukrainian nationality doesn’t even exist, openly reviving an old Tsarist slur.

Russia’s territory straddling the Eurasian landmass from the borders of the European Union to China, with enormous strategic energy-rich regions in between, can play a critical role in the United States’ developing economic rivalry with China. Although the USA has no urgent need of Ukraine’s resources, preventing Russia from retaking hegemony over them, which was lost during the so-called Maidan revolution of 2014, is an important objective.

Likewise a defeat for Russia’s land grab in Ukraine would teach a lesson to America’s ‘strategic competitor’ China. The US could hardly refuse the gift Putin has presented them with a new Cold War forcing countries like Germany to rearm. It disciplines the EU powers, forcing them to break their dependency on Russia’s oil and liquid natural gas pipelines and threatening what they thought would be lucrative links with China’s belt-and-road initiative.

On the defensive

Overall, Putin’s need for ‘aggression’ is ‘defensive’, trailing behind Nato and EU expansion. Putin’s support for ‘frozen conflicts’ by breakaway national minorities—Transnistria, Abkhazia, South Ossetia, the Donbas—are pawns to block Nato membership of the states of which they are ethnically or linguistically distinct regions. Takeovers by pro-Western governments in Ukraine or Georgia provoked violent counterstrikes. The 2008 Georgian invasion of South Ossetia resulted in Russian invasion, the 2014 Euromaidan coup with Ukrainian fascists stalking a purged parliament, the annexation of the Crimea and what was initially popular opposition to the coup in eastern Ukraine providing the pretext for the secession of the Donbas under Russian control.

The Ukrainian government’s continuous attempts to reconquer these regions (against the wishes of the majority of their inhabitants) and its abandonment of the Minsk II treaty under ultranationalist pressure, alongside the reform and rearming of its military, spearheaded by Nato, points towards its future membership and therefore the further erosion of Russia’s security interests.

After two successive years of large scale military manoeuvres and demands for the USA to address Russia’s security concerns failed to produce a result, Putin had either to back down or plunge into an invasion thus inflaming the conflict between Russian and Western imperialism. Though the French and the Germans tried to depressurise the situation by proposing negotiations, the US, totally supported as usual by Britain, was only too happy to exploit Putin’s brutal and unjustified aggression to re-establish the Nato protection racket and thus put a stop to any development of an independent EU imperialism.

Stop the war

The stigmatisation of Russia (and China too) as uniquely aggressive authoritarian powers is totally bogus. The 2003 invasion of Iraq by the US and Britain—the real ‘biggest act of great power aggression since WWII’— puts Putin’s aggression into context. The Nato organised attack successfully projected military power into Iraq from across the globe, capturing Baghdad in three weeks. During the occupation the two sieges of Fallujah were even more devastating than the attack on Mariupol.

The Western powers have used Putin’s war to build support for a huge increase in military spending, Nato expansion and its own future interventions.

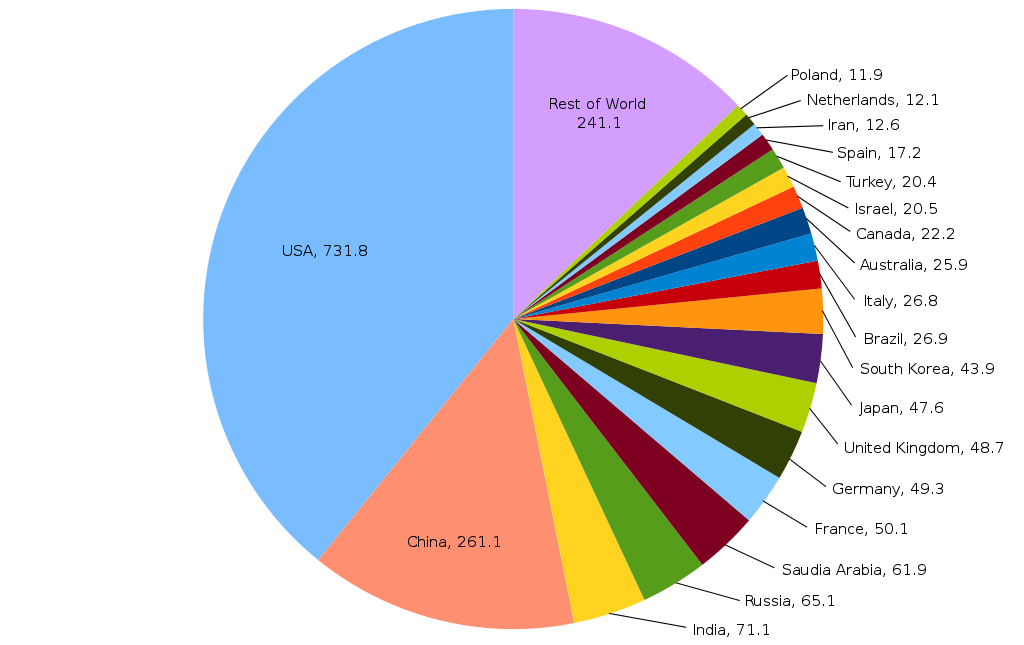

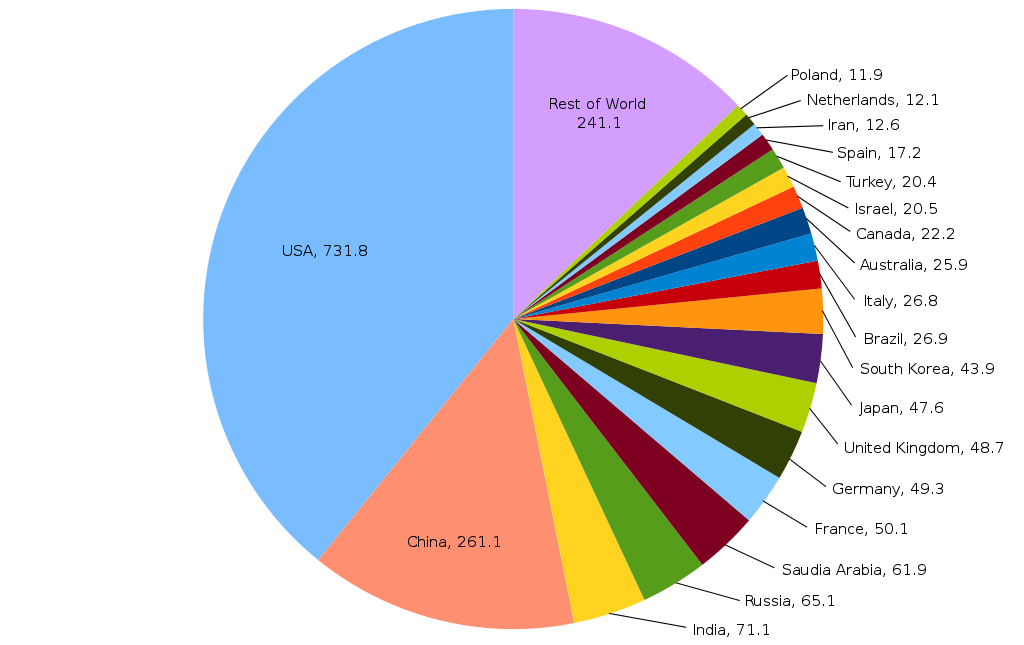

The United States alone makes up 39% of global military expenditure, more than the rest of Nato and more than the next eleven countries combined, including Russia and China. Nato countries’ combined 2021 military spending exceeded a trillion dollars, dwarfing Russia’s $61.7 billion in the same year, while their combined GDP comprised 41.2% of Global GDP compared to Russia’s 1.9%. The US economy is thirteen times the size of Russia’s, while Britain’s is over twice as large (and Britain spent more than Russia on its military in 2021).

For socialists in Britain, like those in the US, Germany and Russia, the main enemy is at home. Socialists in the Nato countries need to emphasise and patiently explain this truth without the slightest support for Putin or Russia’s imperialist interests, while building solidarity with the Russian anti-war movement and the working class movements in every country, including Ukraine.