The filmmaker and artist Steve McQueen has directed five new films about the Black British experience set in West London, where he grew up. The films cover the period of Black struggles from the early 1970s through to the mid-1980s. McQueen has titled the series Small Axe, based on the Caribbean proverb, “You are the big tree, we are the small axe.”

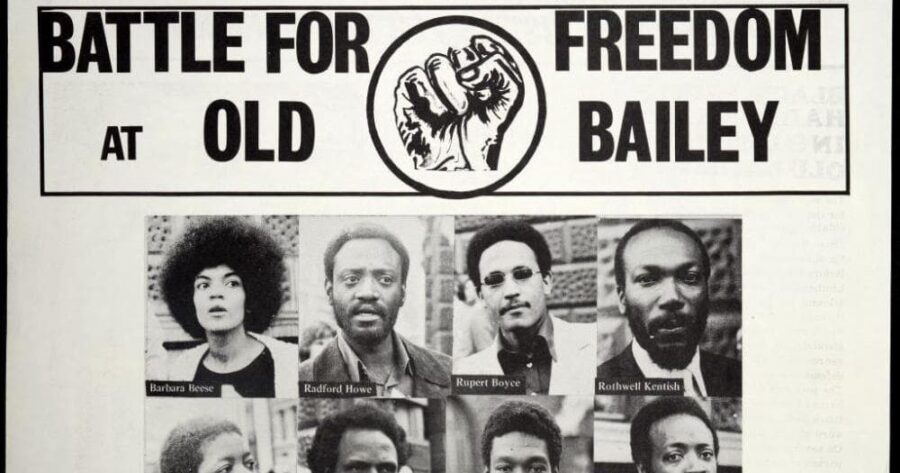

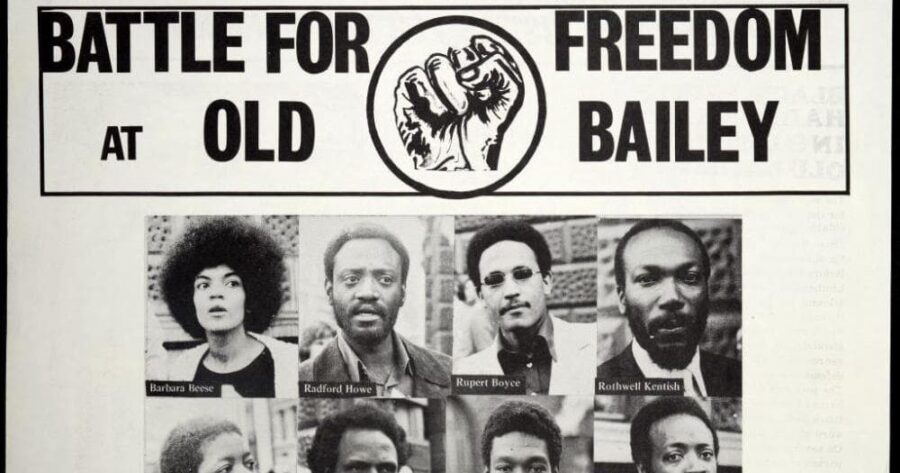

The first, shown on BBC One on 15 November, is called Mangrove and depicts the case of the Mangrove Nine: nine Black activists who led a demonstration against police harassment and violence and were subsequently put on trial at the Old Bailey for incitement to riot. In light of the recent Black Lives Matter movement the films are a timely reminder of the last great period of anti-racist and Black liberation movements and struggles.

McQueen has made a name for himself as a director who dares to make films about social oppression and fighting back against all odds. He won the Cannes Film Festival award for best new director with Hunger (2008), a film about the Irish Republican prisoners’ hunger strike in 1981, and 12 Years a Slave (2013) about the American slave system. Both, like Mangrove, took highly political – and until recently controversial – subjects and focused on the human impact on the protagonists.

The two-hour film focuses on a West Indian restaurant, the Mangrove, in Notting Hill in 1970, which became a community hub for the growing Black community. This was enough for it, like the Black & White Café in St Paul’s, Bristol, a decade later, to become a target for constant police raids on the pretext of looking for drugs. Tensions rise as the raids get more and more violent and aggressive.

A young Darcus Howe (played superbly by Malachi Kirby, who gets Darcus’ accent and delivery style spot on) suggests to Mangrove’s owner Frank Critchlow (Shaun Parkes) that they organise a demonstration against police harassment. Althea Jones-LeCointe (Letitia Wright), who was the leader of the British Black Panther (BBP) Party at the time, led the protesters’ chants – “The pigs! The pigs! We’ve gotta get rid of the pigs!” – cue: the police attack them with a vengeance.

The second half of the film covers the famous trial at the Old Bailey, where the British state was determined to cast the Black Power movement as criminal and “extremist”. Howe and Jones-LeCointe opted to defend themselves, which allowed them to cross-examine the police and speak directly to the jury, as well as providing a political commentary and exploiting courtroom procedures.

The tactic worked superbly. The two, ably assisted by radical white barrister Ian MacDonald (Jack Lowden), quoted the right under the Magna Carta to be tried by one’s peers to insist on an all-Black jury. Although they were unsuccessful, they managed to reject 63 white jurors who gave racist answers to the question, “What do you think about the Black Power movement?” and get two Black jurors on.

Another high point in the drama came when Howe cross-examined the police, who claimed to all see the same events from a polie observation van. Darcus holds up a letter-box sized cardboard slit and asks the three police officers how they managed to look through the same tiny slit at the same time. The sense of joy when the Nine were declared not guilty was a huge moment of catharsis.

The main defect of the film, as it was with Hunger, is that McQueen’s focus on the human side of the story meant that much of the political context was missing. In particular it has to be pointed out that Althea and Darcus were by 1970 seasoned activists in the movement. They were early adherents to the British Black Panthers, which had been set up in 1968 in the wake of a speech given by Stokely Carmichael the previous year in the Roundhouse, Camden.

The BBP did not simply transpose tactics and analysis from the States to Britain; they developed their own as well. Jones-LeCointe was instrumental in shifting the party, which had at its height 3,000 members, towards community struggles, adopting a definition of “Blackness” that included south Asians and solidarising with working class and women’s struggles, as well as physically taking on the fascists. The legal tactics of the Mangrove Nine were later deployed in the trial of 12 Asian activists in Bradford. Darcus Howe went on to form the Race Today collective with Linton Kwesi Johnson and others.

Indeed so successful were the BBP and others in countering the establishment narrative around black immigration and systemic racism, that the Met set up their own “Black Power Desk” to spy on, infiltrate and convict peaceful activists. The importance of the Mangrove Nine trial is that it was the first time a judge had declared that there was “racism on both sides”, i.e. that the police were racist.

While this broadening out of the struggle was intelligently and creatively achieved, it was insufficient for preventing the eventual disintegration of the BPP in 1973, splintering into more localised and more specialist groupings. The political current failed to develop an understanding of class as both a unifying factor in the struggles of the oppressed and a concept that could give a historic meaning – and goal – to the anti-racist struggle.

Nevertheless the film is both hugely enjoyable and moving. It is extremely well acted and the camera work is superb, as one would expect from McQueen with his artistic background (he won the Turner Prize in 1999). The acting and period detail throughout are wonderful.

One of my favourite moments was the playing of Skinhead Moonstomp as the soundtrack on the morning of the verdict, ironic certainly but also perhaps an indication of how things might have turned out differently. That is the task of a new generation of activists, who will hopefully see this film and the others in the Small Axe series and go on to study the politics of this important period of class struggle.